Introduction

Simplicity has been the theme of this series so far. Mostly I’ve just taken food of all kinds – take-out meals, vegetables, meat, eggs – and loaded them on the dryer trays with minimal processing. I pushed a couple of buttons and came back one to two days later to collect food ready to pack into trail meals. Meal prep on trail was equally simple: add hot water, mix, wait a few minutes, and eat.

But there was one notable fail in my experiments: smoothies.

I do enjoy smoothies on the trail. They taste great, pack down small, and contain calories, vitamins, and electrolytes. I’ve ordered them in the past from Pack-It Gourmet, and they are a staple of my trail menu.

So I was pretty disappointed with my first home freeze-dried smoothie. In my rush to prep for the Pacific Crest Trail last year, I freeze-dried a smoothie along with solid fare. The Harvest Right Home Freeze Dryer has two modes: solid and liquid. I had run yogurt on the solid cycle before, and it rehydrated just fine. So I expected similar results for my smoothie.

Alas, it was not to be. The dried smoothie looked fine, but it was hard and rubbery. I couldn’t crumble or tear it. I needed my knife to cut it into serving-size chunks.

When I added water to the chunks, not much happened. They showed little sign of dissolving by the time I finished lunch and was ready to resume hiking. I was sad.

But this tale does have a happy ending. I screwed the lid back on my Vargo Bot 700, stuck it in my pack, and walked. I opened it up during afternoon break and rejoiced to find a fully reconstituted mango smoothie ready to drink.

It was delicious and satisfying, but waiting three hours for a smoothie is unacceptable. When you want a smoothie, you want it right away. I resolved to put the situation to rights when I returned.

In Our Archives: Catch up on the rest of Drew Smith’s series on freeze-drying:

Disorder is the enemy

When I freeze-dried the smoothie, the final product was a glass. A glass is a liquid that has lost its ability to flow. Or rather, it flows very slowly. Whereas water can flow at 10 meters per second (m/s), glass will flow at about 30 millionths of a meter per century. This property has generated the urban legend that glass flow causes medieval stained glass windows to be measurably thicker at the bottom than the top. Unfortunately, this charming story turns out to be untrue.

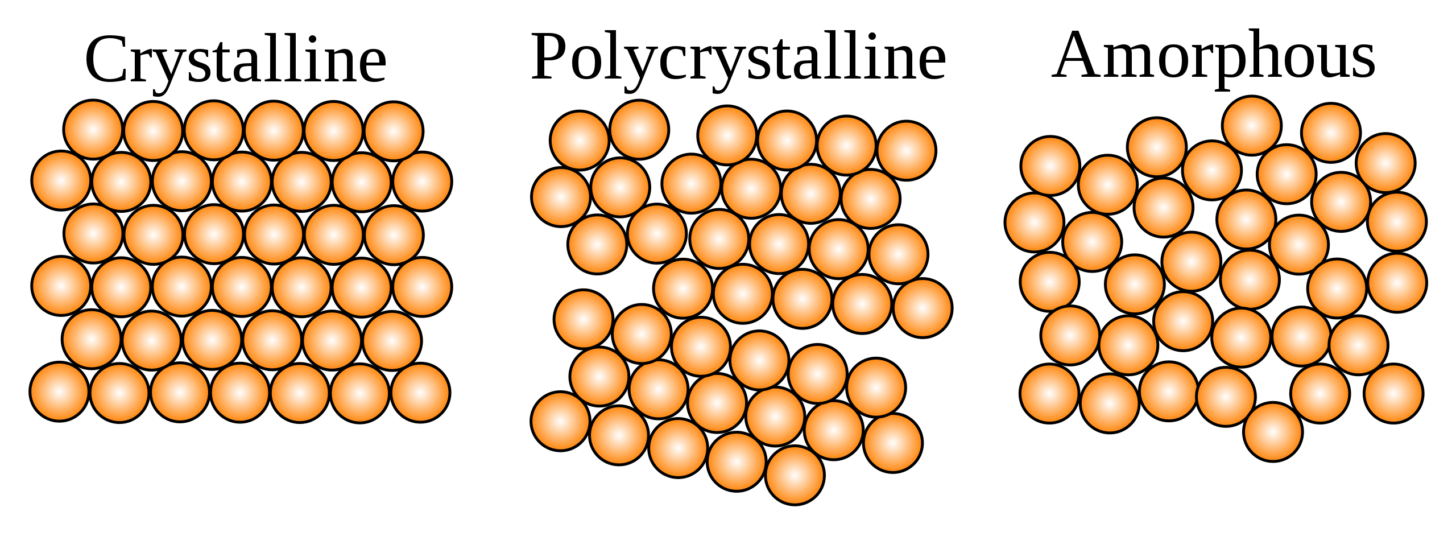

Despite their evident solidity, glasses are considered liquids because of their microscopic structure. True solids are crystalline or polycrystalline, but glasses are amorphous – they lack any long-range order or predictable structure at the molecular level.

Why are glassy foods harder to rehydrate than crystalline foods? After scanning through more food science papers than I care to on this subject, I am not sure, and I am not sure that anyone else is sure either. Foods are heterogeneous materials, and no simple explanation covers all cases. But two factors are probable contributors:

- Because of their ordered long-range structure, crystals tend to dissolve cooperatively. That is, once a little bit of a crystal has dissolved, the rest dissolves much more readily.

- Crystalline foods tend to preserve (or create) pores, effectively increasing the surface area and allowing water to access more of the food. Per the diagram above, a polycrystalline solid (which is what will form in a complex mixture like food) will have plenty of flaws and openings which admit water.

Why do sugars form glasses?

Why did my smoothie form a glass while all the other foods in that freeze-dry run (including unsweetened yogurt) did not? Here I can be a bit more certain: it was the high sugar content. Sugar lowers the glass transition temperatures of liquids. Glass transition temperatures correlate closely with collapse temperatures (see my previous piece How Does Freeze Drying Work?).

Glass forms during the initial freezing process and heats during the secondary drying process. The food collapses, becomes impermeable to water, and resists rehydration. Solids (such as pulp) do not raise the transition temperature but increase mechanical strength, which helps prevent collapse. Commercial food processing companies often add compounds such as maltodextrin when freeze-drying fruit juices or other high-sugar liquids. Sugar-mediated collapse is a well-known problem in the freeze-drying business. The ability to freeze-dry maple syrup to a powder rather than a glass is a benchmark challenge.

In Our Forums: read these smoothie-related threads:

The solution to freeze-drying liquids

Rather than add solids, another approach to avoiding glass formation and collapse is to change the freeze-dry parameters. Enter the “Liquid” program on the Harvest Right Home Freeze Dryer.

The top graph below shows the time course of temperature and pressure on a “Solid” run. The bottom panel shows a “Liquid” run.

Member Exclusive

A Premium or Unlimited Membership* is required to view the rest of this article.

* A Basic Membership is required to view Member Q&A events

Home › Forums › Why is it hard to freeze-dry liquids?