A Catechism

After passing Flaming Gorge Reservoir, that strange blue mirror pooling unnaturally around red hills and cliffs, and turning off the 191 onto a dirt road, we drove past the eastern terminus of the Uinta Highline Trail because there was no sign. We flipped around in the deeply rutted road and let the GPS guide us to where the trailhead was supposed to be. There were a toilet and one white sedan in an otherwise empty and very dusty parking lot. The clouds were patchy, the sky behind them rich blue, and it was hot when we stepped outside the car and pulled the COVID masks from our faces.

We packed hurriedly, and I made a last-second decision to carry a grapefruit. Then we started down the two-track past the post where the sign should be, or once had been. Walking through the forest, we noted its relative health compared to other parts of the Uintas. We started at 3:15 in the afternoon and hiked until we realized we hadn’t seen water in a long time. I checked the map and found a blue squiggle labeled Big Brush Creek, meandering through a meadow called Manilla Park. When we reached it, we ambled down the meadow until it transitioned from dry to wet, and there on the edge of the marsh, we dropped our packs and made camp.

The next day we walked on dusty logging roads and through forests consisting of equal parts stumps and new trees. We passed trucks parked on the edges of lakes, jarringly shiny in all that matte landscape. We heard heavy machinery roaring and beeping somewhere in the woods. It wasn’t until late afternoon on the third day that we actually found the Wilderness boundary at the top of North Pole Pass and looked down into the Uinta Basin. The Wilderness sign stood propped up by a pile of rocks on the subtle apex of rounded, bleak tundra. It divided the land of humans, roads, and motor sounds behind us from the land described in the Wilderness Act of 1964 as “untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

We were headed into a land that would provide us with a sort of religious experience. The Catechism of Observing Otherness. A view of the world without the humans. A world which hints at the ancient times from which we sprang. It hints at The Before.

Before there was anything at all – Before we were able to meddle. It reminds us of our source within the earth, the universe. We went there to be humbled by this vision, while on our backs, we carried everything we needed in order not to be killed by it. We had rain jackets and tents and sleeping bags and food procured from grocery stores. And we experienced that very tension, skirting the edge of death intentionally, looking off the edge into its void while remaining firmly tethered to life by our gear, skills, physical strength, willpower, and luck.

As we climbed to the top of another pass, seven elk dashed across the trail in front of us and ran down the hill to the green treeless meadow below. A mother stopped and turned and called to her babies, the last to descend. And then they all ran to where ribbons of water from the snowmelt subtly pleated the green velvet, following gravity and geology to a shallow blue lake.

Not ten seconds later, a mountain goat ascended the trail in front of us. It moved strong and fast and didn’t even look in our direction. This was the world we came to see: that place where the human is a visitor but doesn’t remain. It felt like a pristine – ahistorical – Eden, and it filled me with awe. It was the world separate from the human world, rolling on intentionless and insulated from the influence of ideas. This separate world couldn’t be infiltrated by concepts like religion or physics with all their limits. It just is what it is.

This Ground is Not Prepared For You

Wilderness didn’t always elicit such feelings of wonder and awe; it used to be viewed as the outer margins of civilization. It’s described in the Bible as a fearful place one went only against one’s will. For years, Europeans thought it was the darkness on the edge of town, which was empty, deserted, barren, savage, and ultimately useless besides the fact that it contained the raw materials of civilization. In short, it was an undesirable place.

And then its meaning started to shift. Henry David Thoreau viewed it as something simultaneously awe-inspiring and frightening. He described Mt. Katahdin in Maine as “vast, Titanic, and such as man never inhabits… She seems to say sternly, why came ye here before your time? This ground is not prepared for you.” Of course, while Thoreau was climbing Katahdin in 1846, Black people all across the country knew wilderness as the place where they might be lynched. Wilderness has, at times, meant very different things to different people.

Later yet, John Muir recounted a trip to the Sierra. “Perched like a fly on this Yosemite dome, I gaze and sketch and bask, oftentimes settling down into dumb admiration without definite hope of ever learning much, yet with the longing, unresting effort that lies at the door of hope, humbly prostrate before the vast display of God’s power, and eager to offer self-denial and renunciation with eternal toil to learn any lesson in the divine manuscript.”

This version of the wilderness experience seemed closest to what I was seeking when I set foot on the Uinta Highline Trail. I found myself humbly prostrate before the seven elk crossing the meadow.

This romantic sublime view of wilderness described by Muir is foundational to conservation in the United States, but was only possible in places that were untouched by humans, places that were pristine Edens, places where no one had set foot since the day God stopped creating. The only problem with this was that these Edens didn’t actually exist! People had been walking every square inch of America for at least 15,000 years before Muir. So, when forest preserves and national parks began to be created, Native people were removed from them so the parks could be advertised to the wealthy white tourists as safe, uninhabited, and most importantly, unchanged since the dawn of creation.

In the late 1800s, Americans began to lament the disappearance of the frontier. Moreover, wealthy white men wanted something empty to be able to push into, to conquer. If wild places were so important in the construction of the United States, then the future of the country must lie in their preservation.

In his famous essay “The Trouble with Wilderness,” the environmental historian William Cronon says, “It is no accident that the movement to set aside national parks and wilderness areas began to gain real momentum at precisely the time that laments about the passing frontier reached their peak. To protect wilderness was in a very real sense to protect the nation’s most sacred myth of origin.”

Recreating in the wilderness became an elite activity. And ironically, the construction of national parks closely followed the final Indian Wars, and Native people were removed and placed on reservations. It’s ironic as well, that while these places had a façade of wildness, their boundaries were policed to keep violence out. Real wildness, frontier wildness, was full of conflict. The wildness we experience today, like the wildness I saw in the High Uintas, is lacking a human element that could be even wilder. As an elite, white, male, I don’t have to watch my back the way I would have in the mid-1800s. Lightning and hypothermia are separated from other real (and objectively wild) threats, such as human conflict.

The Beguiling Mask

According to Cronon, all these things describe the problem with wilderness. “Wilderness,” he says, “hides its unnaturalness behind a mask that is all the more beguiling because it seems so natural.” This idea was appalling to me when I first came across it, and if it gets your hackles up, you’re not alone.

“But it is natural!” I’ve wanted to scream. It’s nature, isn’t it? It’s true enough that we’re going to have transcendental encounters with the more-than-human world in the wilderness, and these are real. But the islands of land in which we have these experiences are a cultural construction. The elk I watched run across the talus, tundra, and meadow, and disappear into the mysterious distance felt wild. The whole encounter was indelibly wild. It caused in me a feeling of awe, joy, melancholy, elation, and wonder. These were feelings I couldn’t articulate or define, but the combination of which continues to drive me to walk through these wild places.

So, there I was, following in the footsteps of Muir except in the High Uintas instead of the Sierra, in search of the romantic sublime, something at once frightening and beautiful, a religious experience impossible to have in my suburban neighborhood. And I pushed into this imagined frontier, almost squinting to blur it into something it isn’t, to see myself as the first to descend a rocky pass and rest against a glacial boulder placed there on the day of creation and which no one has seen since. To be the first to fill a bottle from clear snowmelt running through squat willows and Indian paintbrush.

The problem with this experience, according to Cronon, is that it dishonestly leaves humans out of the equation. Even worse, it creates an intractable nature/human. So, in the context of “The Trouble with Wilderness,” the big question becomes: What would it mean to backpack (or engage in other forms of recreation) while being fully aware of historical contexts? What would it mean to consider humans as part of nature instead of separate from it? Am I willing to temper my desire for the pristine with an awareness that the pristine is a cultural construct? Can I try and reinstate the past in my imagination?

As I walked huffing and puffing over Porcupine Pass, I tried to see Paleo-humans with tools chipped from quartz-sandstone following big game to the edges of the glaciers. The glaciers disappear and I see horse herds in Oweep Basin. We pass their bones, whiter than snow with lupine and columbine protruding from hip-sockets and eye-sockets. Wall tents are staked to glacial moraines, and smoke pours from them as the sound of clanking pots and pans comes from within, and distant voices echo through the healthy lodgepole forests. The sounds mingle with the hermit thrush’s pentatonic call that still echoes through dying forests today. I hear rocks crashing together as CCC crews construct a dam along the outlet of a lake.

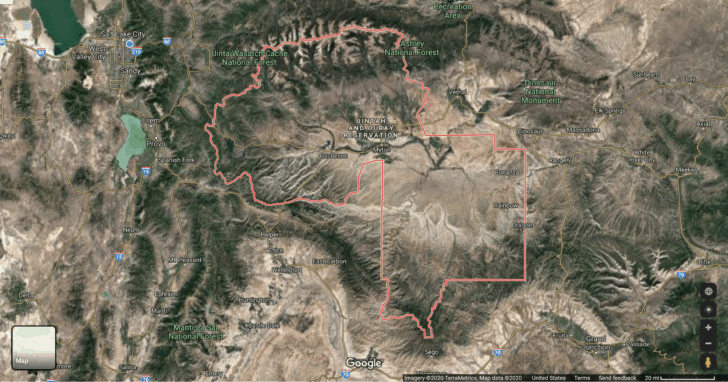

We stopped for lunch where Oweep Creek left the long meadow to enter pines, spruce, and fir. I pulled out my map and noticed a clumsy line running along the entire spine of the Uintas labeled “Old Indian Treaty Boundary.” When Utes were rounded up out of the Wasatch Front and other areas, and then dumped in the Uinta Basin, their promised territory extended all the way up past the very place where I sat. The Uintah Valley Reservation was designated in 1861, the Ouray in 1882, and in 1886 they were combined to encompass 4 million acres of land. But as was always the case, Native territory got whittled down to nothing like a boy scout trying to make a spoon out of soft aspen wood. Pretty soon there’s nothing left.

While this was obviously Native land before the treaty, I found it all the more upsetting that it was also promised to remain so under a treaty that was no longer being honored. Indeed, if you type “Uintah Ouray Reservation” into Google Maps, the original swath of 4 million acres is still shown, including the entire southern slope of the Uintas, the whole Uinta Basin, much of Desolation Canyon, and a gigantic portion of the Tavaputs Plateau.

Today, tribal land includes only 1.2 million acres of this original area, patchy and disjointed. Presidential proclamations created townsites within it. On July 15, 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt absorbed almost all of the southern slope of the Uintas, the Native land, into the Uinta Forest Reserve. Three years later, by executive order, he renamed this area Ashley National Forest, the very forest where I was sitting looking at my map. Soon thereafter, dam construction began, an effort to standardize water availability for a growing population of white settlers within the reservation boundaries at the base of the mountains.

Does this remembrance diminish the sublime experience? If it does, I don’t care.

Not only does it improve my overall backpacking experience, but it’s also an absolute necessity to know a place’s history. I prefer to backpack while aware of my own privilege, aware of the human histories embedded in a place that is only pristine if you actively ignore its history. Cronon reminds us that “Wilderness always displays an escape from history, an erasure, running from something to a past that never actually existed.” I don’t want to experience wilderness in this way; I want to be fully aware that my 104-mile Highline trip took place in what is supposed to be native land.

But let me acknowledge the merits of Wilderness, National Parks, and other protected areas. While there is nothing natural about the idea of wilderness, it doesn’t mean there isn’t any value in it. We’ve ended up with islands of relatively intact ecosystems, and this is a good thing! We protected them often for the wrong reasons (beauty, the feeling of the sublime associated with such grandeur, etc.), but we protected them nonetheless, and it feels important to remember both of these things at once. National Parks and Wilderness areas are better off this way than they would be if we left them open to exploitation.

That said, I may have to rethink the way backpacking, my preferred method of recreation, influences which landscapes I choose to care about, and which I choose to ignore. This could mean paying more attention to pastoral or suburban areas between core protected areas.

Considering conservation in these places could start to undo that human/nature division that is so seductive, which props up the concept of wilderness. It would suggest that we have to consider ourselves as a part of nature, part of everything. It would start to break down the fantasy Cronon laments.

This fantasy is what worries Cronon the most. He’s concerned that wilderness causes us to dismiss the nature all around us, and forget that conservation should happen in the places we are, not just the places we visit. He doesn’t want us to forget about that liminal space that people have inhabited for all of human history: working with nature, using it, making a living. Cronon’s final plea is for us “to discover a common middle ground in which all of these things, from the city to the wilderness, can somehow be encompassed in the word “home.” So how do we do this?

For me, it’s two-fold.

1. Fully acknowledge the histories of places where we backpack.

2. Acknowledge wilderness not associated with backpacking at all: in the city, in our own neighborhoods.

Remembering that the High Uintas Wilderness has been occupied, used for subsistence, altered, stolen, and renamed should begin to illuminate a kinship between it and the sycamores that line the street in front of my house, and the squirrel that runs across the powerline between them. All of these things are the more-than-human world affected in some way by humans. We should endeavor to care for all these things as much as we can, regardless of their connection to backpacking or other forms of recreation.

Further Reading:

- William Cronon’s “The Trouble with Wilderness”

- Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation by Carl Jacoby

- The Wilderness Act of 1964

- The Writings of Henry David Thoreau

- John Muir’s My First Summer in the Sierra

Related Content

More thoughtful trip reports from our Backpacking Light authors

- Benjamin Kilbourne – Backpackers Should Be Amateur Naturalists

- Daniel Sizer – Getting Lost in an Urban Wilderness

- Andrew Marshall – Walking in Circles: A Tahoe Rim Trail Thru-Hike

- Ryan Jordan – Wind River Backpacking: Sawmills, Tenkara, and Trout in the Popo Agie Wilderness

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Product mentions in this article are made by the author with no compensation in return. In addition, Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › Can Wilderness Include Humans?