Introduction

Knowing where you are in the backcountry and identifying that location on a map (“fixing your position”) is an essential skill. Doing so with analog tools (e.g., map and compass) seems to be a lost art, having been replaced by the digital position fix marker found in GPS smartphone apps.

In this skills article, you’ll learn a fundamental map use technique – what lines of position are and how to use them to fix your position on a map in the backcountry.

What is a line of position?

If you look at your map and say, “Hmmm…I’m somewhere on this map.” that’s not going to inspire a lot of navigational confidence.

However, if you knew with certainty that you were somewhere along a line on the map, that may make you feel quite a lot better about where you’ve come from and where you’re going.

A line of position, or LOP (sometimes called a “position line”) is a line on the map where you know with 100% certainty that you are somewhere along that line.

Lines of position may be straight (e.g., a boundary fence) or they may be nonlinear (e.g., a trail).

What are examples of lines of position?

The most important thing about a line of position is that it must always be identifiable on a map. A stream you discover in real life that isn’t on the map cannot be a line of position.

Lines of position can be manmade features, topographical features, terrain features, or sighted bearing lines.

Manmade lines of position:

- trails

- roads

- fences

- powerlines

Topographical features that can serve as lines of position:

- ridges (where peaks and passes live)

- valleys (drainages)

- steep slopes or cliffs adjacent to significantly less-steep terrain

- benches

- plateau boundaries (i.e., topographic perimeter)

Terrain features that can serve as lines of position:

- streams

- lake shorelines

- changes in vegetation

Sighted bearing lines can also serve as lines of position. These are the imaginary lines drawn between a known landmark and your current position. In most cases, they require the use of a compass.

The exception to this is when you, and two other (known) landmarks lie along a straight line. This type of LOP is called a transit line. A compass isn’t needed to draw a transit line.

Two or more lines of position = a position fix

The magic happens when you arrive at a point where two lines of position intersect. At that point, you can fix your precise location on the map.

One of the most obvious intersections of two lines of position for hikers is where a trail crosses a stream. As long as you’re paying attention as you hike, and make a mental note of major stream crossings that correspond to mapped streams, this is a reliable method for fixing your position. However, it can become confusing if you are hiking in particularly wet areas, or during the early summer, when you may cross several streams that are too small to appear on the map.

Any two lines of position mentioned in the previous section can be used to fix your location – the combinations seem limitless. The next section outlines some common examples.

Examples of intersecting lines of position used to fix your position on a map

1. Trail LOP intersects another trail LOP at a trail junction

In most National Parks and other popular hiking destinations, we can enjoy the informative benefit of signed trail junctions. In the absence of signs, we can still use the information reliably – assuming our maps are up to date!

2. Trail LOP intersects a stream LOP at a bridge

This method is most reliable for significant streams that flow year-round, are mapped, and travel through topographically-obvious valleys that we can visually identify in real life.

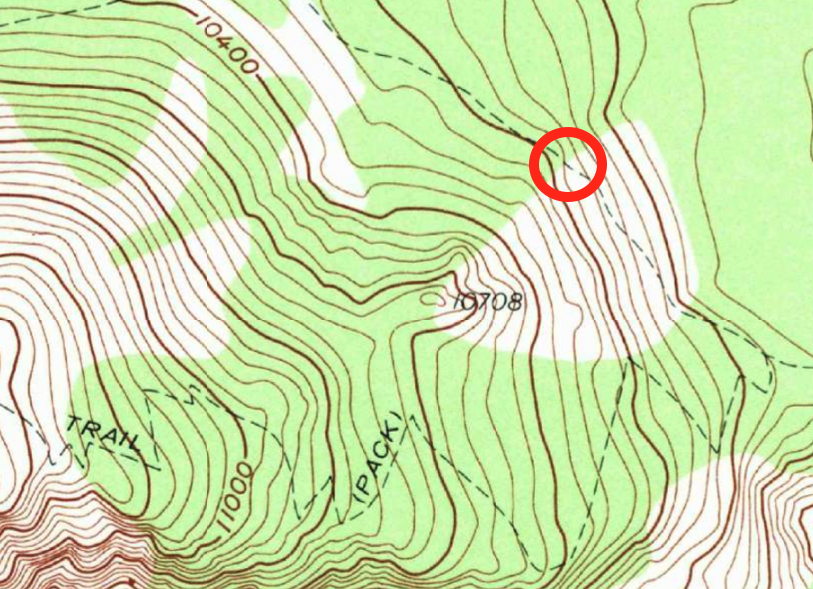

3. Trail LOP intersects a vegetation boundary LOP when it enters a meadow

This method requires updated maps. Be cautious of wildfire-burned areas that have appeared before the printing date of your map – vegetation cover can change significantly with wildfire.

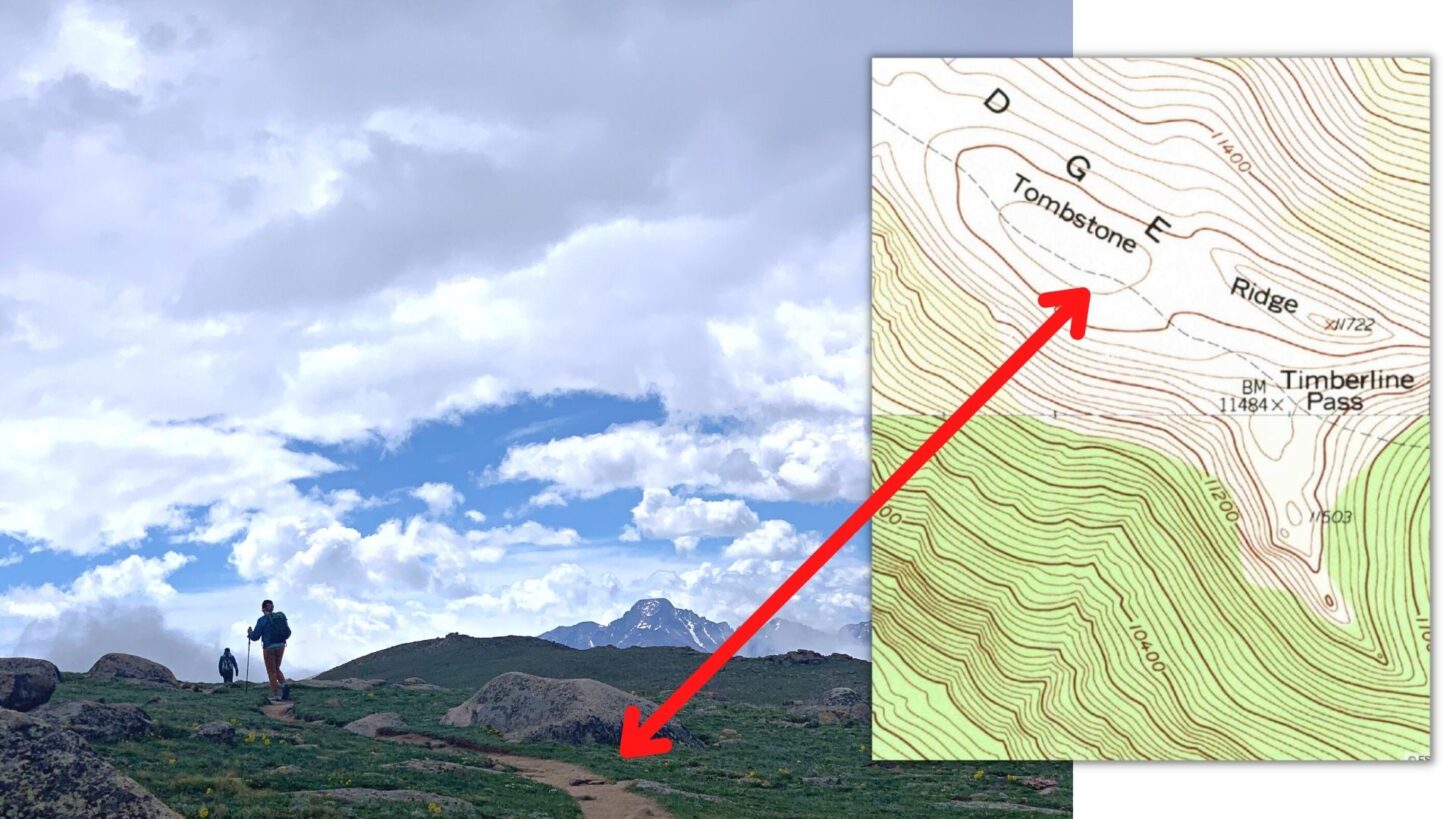

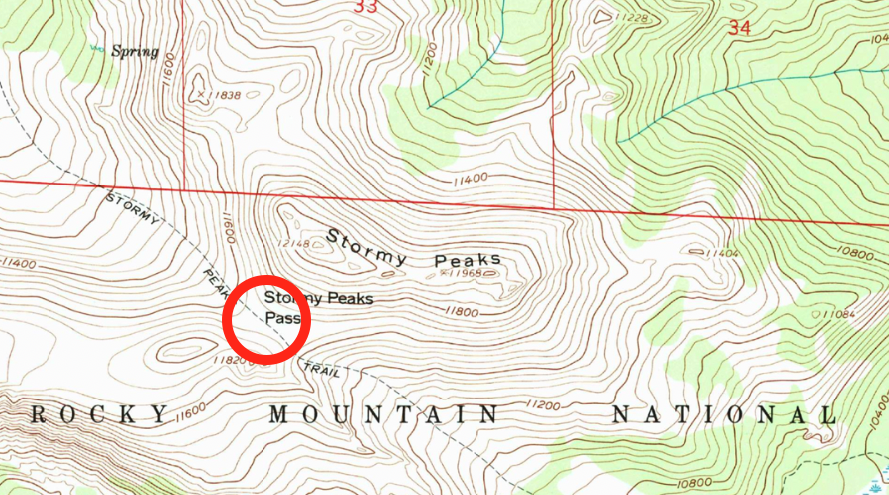

4. Trail LOP intersects a ridge LOP at a pass

Recognizing passes, ridges, and other topographic features requires practice. Make it a routine to take your map with you everywhere and correlate the terrain you see in real life with the shapes of the topographic lines on the map.

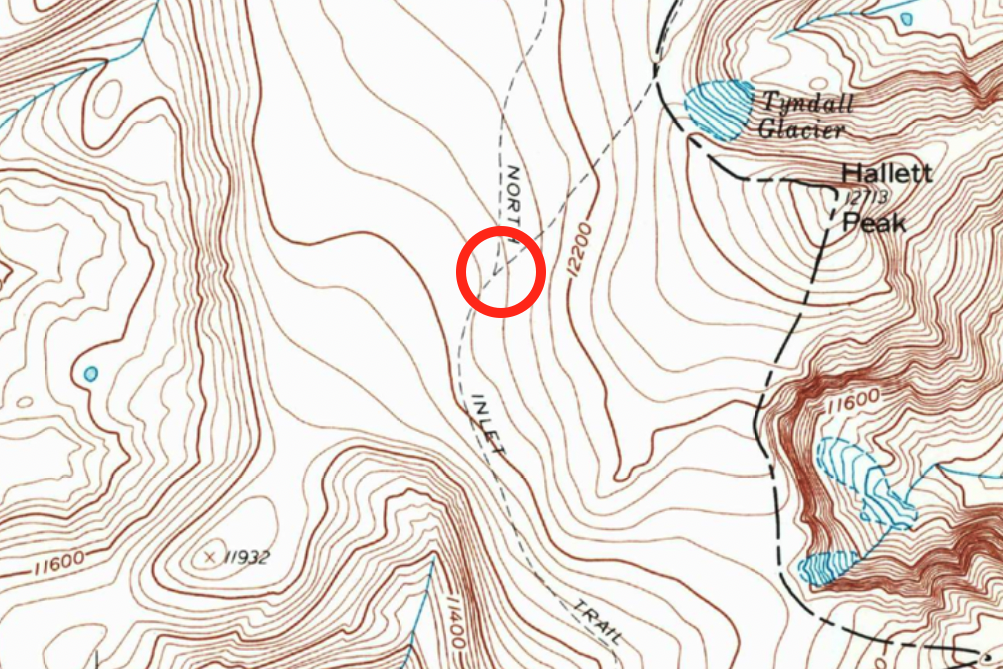

5. Sight line LOPs (compass required) to known landmarks that intersect with topographic LOP

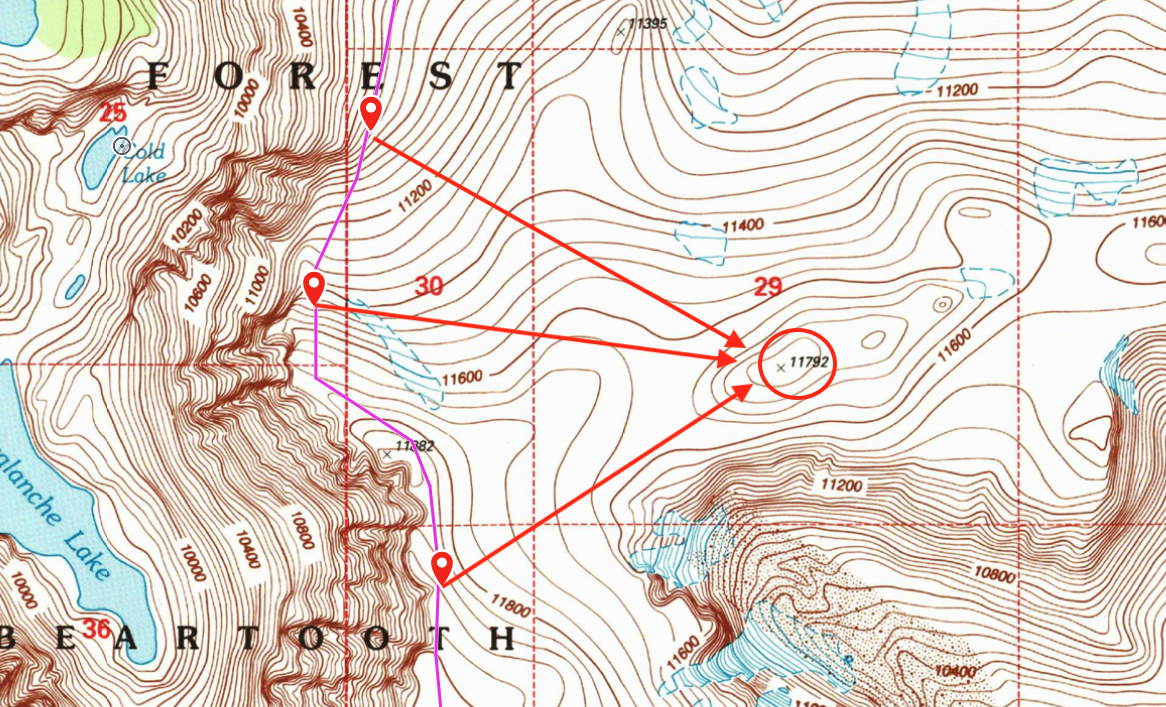

In the absence of trails, you’ll need to get more creative. Here’s an example of a mountaineering route I attempted up the north ridge of a prominent peak in Montana. Most of the climb was performed in low-visibility conditions (cloud cover). I was handrailing (a technique where you follow a natural terrain feature) along the western edge of the summit plateau, which fell off steeply to cliffed terrain. So when the clouds cleared enough, I was able to sight a bearing line to Peak 11792 (compass required), and then draw that bearing line onto my map. My approximate position fix was where the bearing line LOP intersected my route LOP at the western edge of the plateau.

6. Trail LOP intersects a transit line LOP (no compass required)

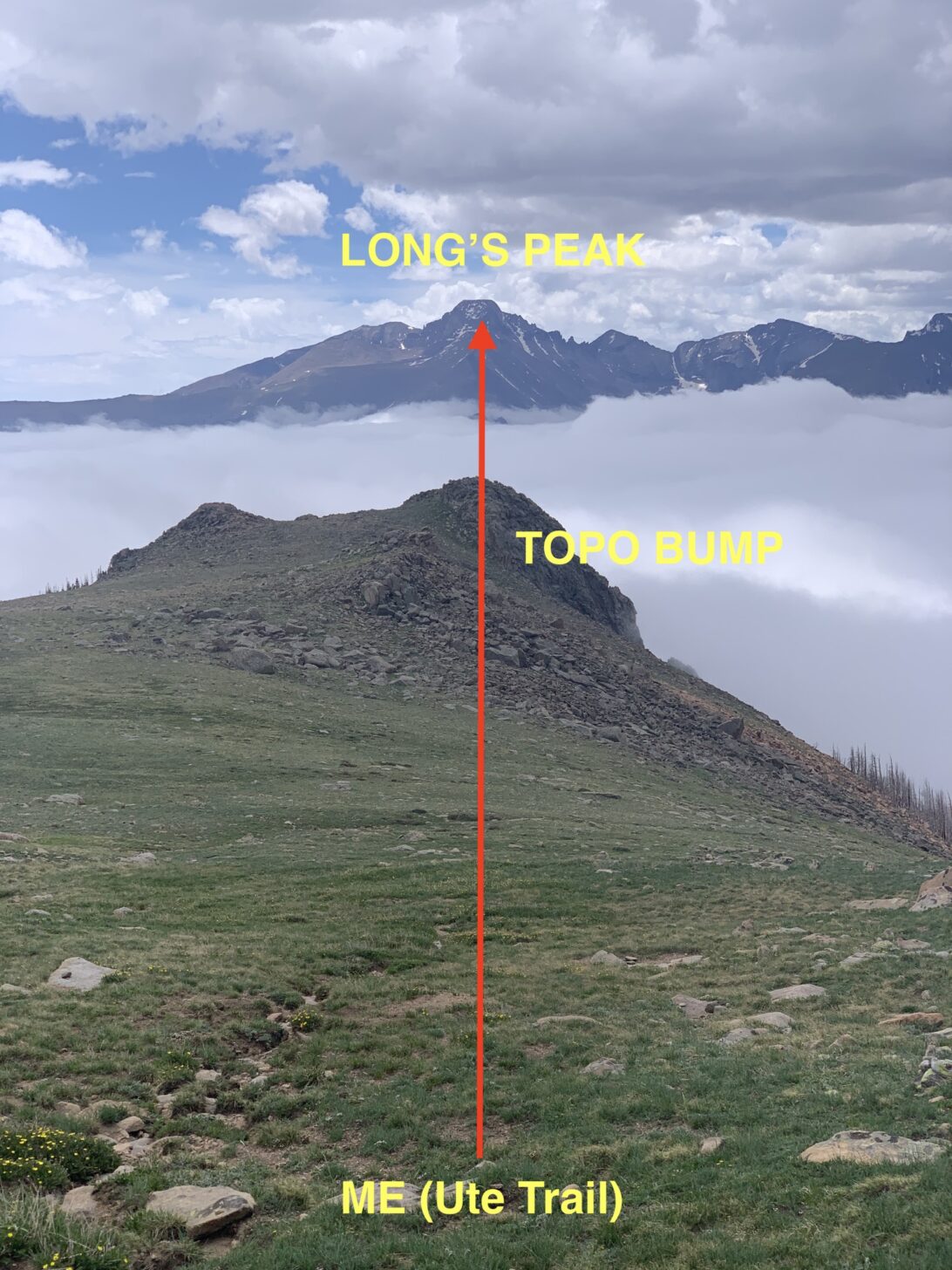

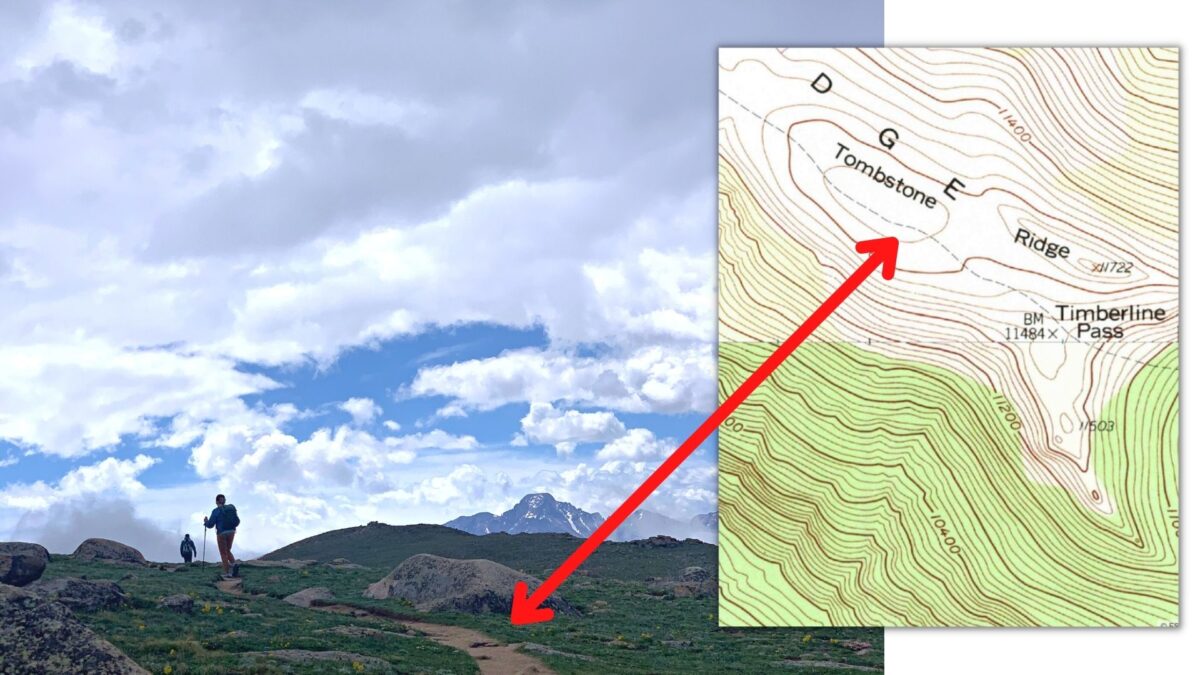

We recently hiked the Ute Trail in Rocky Mountain National Park, and encountered a classic example of a transit line LOP. A transit line is a straight line that intersects your current position and two visible landmarks. Transit line LOPs can be used to orient a map, or sight a bearing without using a compass.

The two landmarks I observed were a small unnamed topographical bump (foreground) and the very prominent north face of Long’s Peak (background):

Now, simply drawing a line on the map from Long’s Peak, through the topo bump, and intersecting the Ute Trail, I can fix my position on the trail. In addition, by laying the map on the ground, and rotating it so the transit line drawn on my map is parallel to my line of sight to Long’s Peak, it’s now oriented. All this without using a compass – such is the power of a transit line.

Conclusion

Understanding how to identify and use multiple lines of position (LOPs) to fix your position on a map is one of the most valuable navigation skills you can learn. This technique does not require a compass most of the time, so it’s very fast and simple to learn. Practice it!

Learn More

Join us Saturday, July 2 at 9 AM US Mountain Time for a Map-and-Compass Member Q&A live webinar. I’ll expand on the topic of lines of position to include compass work, and we’ll address more analog techniques for backcountry navigation.

Home › Forums › Using lines of position to fix your location on a map