Introduction

A one-person tent—of whatever brand—is sized at some barely tolerable minimum that varies slightly according to its design. Whether all of this cramped stringency and suffering actually pays off for backpacking is unclear. Substituting a “two-person” tent may add merely a pound (or in many cases, less). The idea has been around at least since the Victorian Era and probably the Stone Age—always with the same tradeoffs. Marginal advantages of the solo tent include reduced bulk and weight. When beset with brush or uneven ground and in stealth camps, its small size is versatile for siting. My fascination with this equipment is not, however, primarily practical. I’ve long imagined the minimal one-person shelter as a symbol and marker of backpacking’s austere freedom.

And so it was that I recently acquired an offset-pyramid tent from 3F UL Gear—the CangQiong 1 (1.5 lbs / 740 grams). The company offers a small line of tents that rely on a single trekking pole for set-up. Based in Xiamen, China, 3F seems to rely on Google Translator for its English-language marketing. This tent-maker helpfully describes the CangQiong 1 as “designed for dry conditions.” Yet I interpret this forbidding description with sunny optimism.

Knock-offs, “Originals” and History

First, however, it’s best to acknowledge the obvious: these tents are inexpensive knock-offs derived from successful American brands. The “originals” are more durable and weatherproof—and cost more. Producing copies and imitations is a long-established practice among tent-makers, with examples continually appearing. Outright piracy presents moral and legal issues, but I’ve no information nor opinion on whether this pertains to the 3F Ultralight Gear CangQiong 1.

Moreover, choosing between global market “philosophies” of any stripe is not my intent—least of all at the cash register. The concept of backpacking implies severely minimizing all its trappings. Sometimes this minimalism expands—at least in my imagination—to include matters of price. At some point, many of these questions become trivial and arbitrary.

Offering dire critiques of non-premium equipment is a long-standing pastime for certain hikers. But memoirs of the now elderly British mountaineer Chris Bonington recount sharing a ledge high on the Eiger with Don Whillans while both inside the same jumbo-sized plastic bag culled from a trash heap. The infamous Whillans chain-smoked cigarettes through the night. The bag’s quality wasn’t recounted as an issue. But in this instance the pair may have been happier in solo shelters—even if still failing to complete their route as a team.

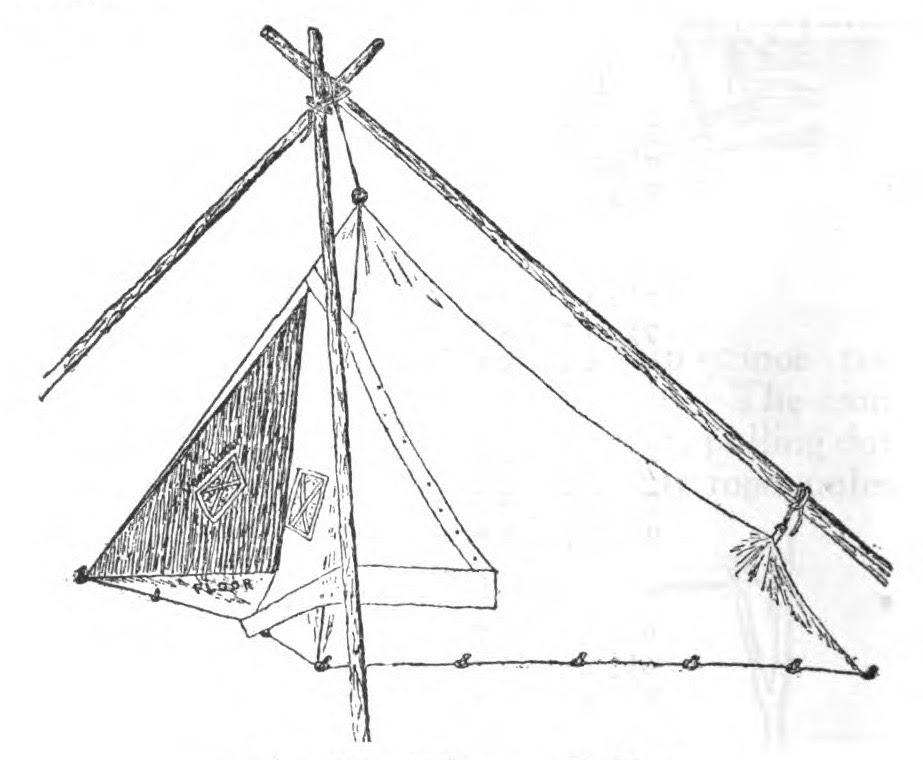

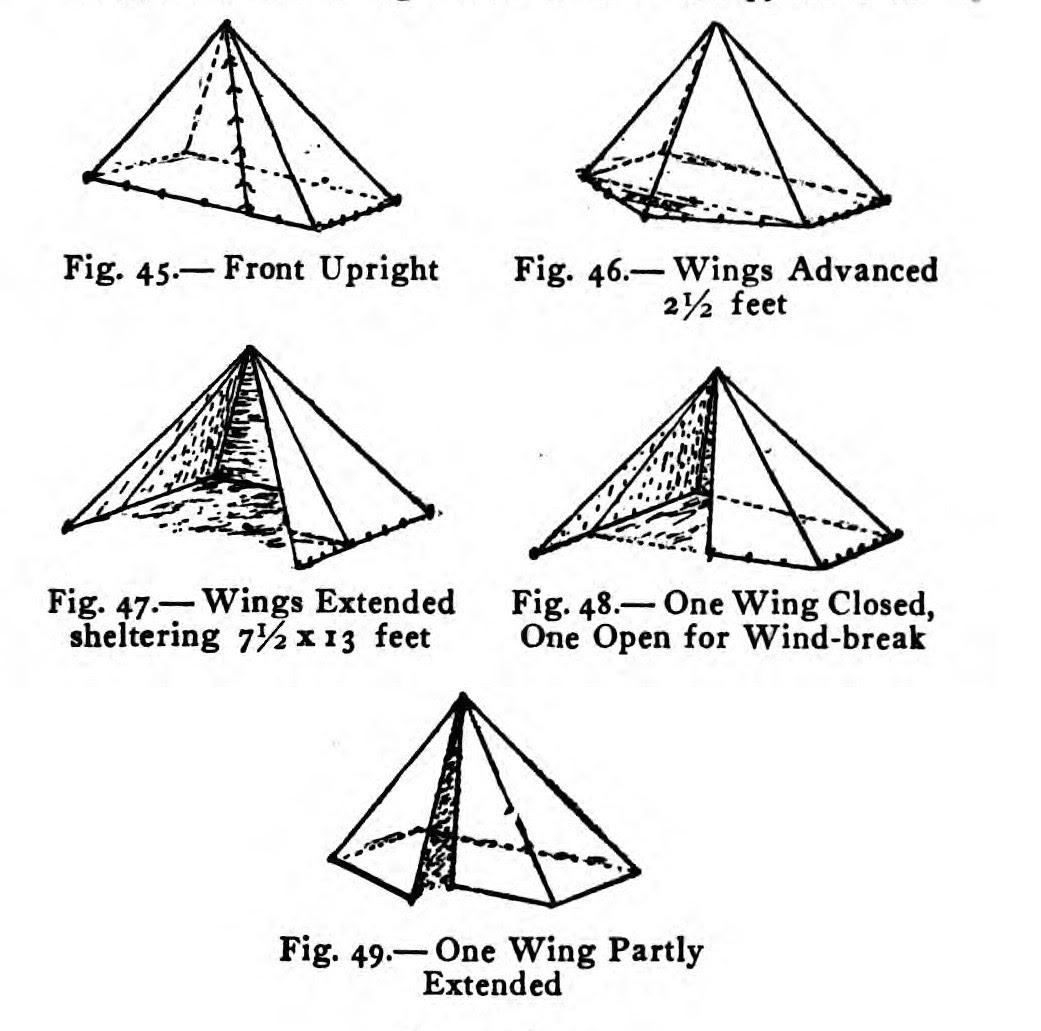

The 3F tents are based on recent patterns, but also reminiscent of much older, classic designs —especially the Compac Tent (3.4 pounds, 1.5 kg ) and the Royce Tent (4 pounds, 1.8 kg). Horace Kephart referenced these old tents in his 1911 manual Camping and Woodcraft. The author noted that Thomas Hiram Holding of London supplied a wedge tent “of Japanese silk, that weighs under 12 ounces; and it is a practical little affair of its kind.” But for the hiker who “goes out alone for a week or two at the fall of the year, or at an altitude where the nights are always cold” Kephart advised, “take a half-pyramid tent, say of the Royce pattern, but somewhat smaller.”

As of 1969, Recreational Equipment Inc.’s catalog included a “One-[Person] Tent” of tapered wedge design, with a canopy of finely woven cotton and pictured in deep blue. It may have been part of their line of several Swedish imports. Much lighter solo wedges in coated nylon were already available through a contemporaneous Eddie Bauer catalog.

Proliferating Designs

Today among leading one-person designs, the 28.6 oz (810 g) Durston X-Mid 1P is $200 and made of polyester, said to reduce stretching in rain. Six Moon Designs, one of at least several comparable small firms in the U.S., has produced a matter-of-fact YouTube video, showing that its Lunar Solo tent ($230) employs more durable and waterproof textiles (polyester) than competitor knock-offs, and yet is marginally lighter. The Swedish firm Hillenberg offers a well-established line of heavier singles in the range of $600 that seem suitable for alpine blizzards. But even as ingenious solo tent designs have proliferated, the whole genre is called further into question when lined up against very small, single-wall two-person domes (Black Diamond Equipment First Light, $370) available for the past 20 years.

Feeling penurious and with a genuine aesthetic revulsion toward domes, in March 2020 I acquired the 3F Ultralight Gear CangQiong 1 offset design. A longstanding but selective attraction to “reverse snob appeal” slightly clouded my judgment. The actual name of this product is rarely used in English-language marketing. It’s called instead of the “Single Person Tent Outdoor Ultralight Camping Tent 3 Season Professional Nylon Silicon Coating Rodless Tent.” Delivery from Xiamen took eight weeks.

In Michigan’s Lower Peninsula recently, I spent four October nights in the CangQiong 1, confirming its high-quality stitching and carefully designed reinforcements. It shrugged off light showers. Although smaller and more than twice the weight of Holding’s silk wedge of 1911, this tent is indeed “a practical little affair of its kind”— and yet another sign of human progress.

In March, AliExpress listed the model at $70, but payment difficulties on that site sent me to Amazon, which charged about $100. Now, seven months later, its price is up substantially, although a tent branded Flames Creed (not 3F) at a glance appears identical and is more reasonable ($89) as of this writing.

Cheap Tents Compared

I can most directly compare the CangQiong 1 with recent experience of a different one-person tent: the Wenzel Starlight. Its pleasingly classic, “mountain tent” form, and even an A-frame door bring to mind 1960s REI backpacking tents. Mine was a $28 Walmart purchase. From April to November last year, I spent a dozen nights in this relatively spacious, two-pound (896-gram) tent during walks along the western border of New England. But my Starlight has a sad secret: On a November evening in the Taconic Mountains, the “beak” or hood shielding its door ripped as I carelessly inserted an A-frame pole too tightly. This tent, now discontinued by Wenzel, remains marginally usable and repairable, but I’m uncertain of taking the trouble and expense.

The 740’s construction inspires incremental confidence. It’s also preferable for its spacious, well-protected vestibule and door, and 10 inches (25 cm) of extra headroom. Although the 740 may at any time meet Starlight’s fate, it’s more likely to stand up adequately. For 10 years, I gradually wore through the floor of a tent similar to the Starlight, acquired for $19 from a local version of K-Mart. Clearly (to me), cheap and lightweight tents are potentially reliable. Moreover, recent experience may now inspire slightly greater tent-handling care.

Condensation Complaint Department

In mild weather, condensation inside coated tents, including the Starlight and 740, is largely insignificant. But a couple of nights spent hard by the banks of a midwest river near-freezing saw the 3F Ultralight Gear CangQiong 1 produce copious condensation by dawn. (In similar weather at a less dank location, this same tent stayed reasonably dry). Long ago I spent a night of inexpressible misery inside the K-Mart pup tent after a predicted rainstorm unexpectedly produced eight inches of wet snow at nightfall.

For several years following this pup tent incident, I avoided down sleeping bags in all but summer weather—regardless of available tentage. I acquired various floorless tarp shelters—solo and otherwise. Liquid simply drains away into the snow or dirt. Banked snow or even autumn leaf-drop can seal the perimeter from cold drafts. Moreover, floors may be the quickest tent component to wear out. But sewn-in floors and netting are an indispensable defense against insects in season and serve as a reassuring barrier against mud and crud.

Still fearful of drowning in an icy sea of condensation, I now rely on a sleeping bag cover or bivouac sack to protect from any rare discomfort inside sketchy shelters. A cover also shields the delicate sleeping bag from dirt and abrasion, while conveniently serving in lieu of a stuff-sack for transit and as a closet storage bag. In relevant circumstances, covers with fully waterproof “floors” can also make a groundsheet redundant.

Unlike many 3F products, its Tyvek Bivy bag (7 oz / 200 g) appears to lack narrowly comparable competition. Recently advertised at $20, it performed well inside the CangQiong 1 on four autumn nights near freezing. The unit is doubtless somewhat weatherproof when new and/or not excessively laundered. It’s too narrow, however, for winter sleeping bags and lacks a reliably waterproof floor. Various do-it-yourself Tyvek bags seem feasible for the talented.

Other, much more durable and desirable light covers are available—starting at about $100.

Further Reading:

- Matthew De Abaitua’s memoir The Art of Camping (Penguin Books, 2011) includes a survey of camping history and literature from a British perspective with significant detours to America. DeAbaitua’s bibliography, including works by Kephart and Holding, covers 17 pages.

- Dan Durston, a U.S. designer who reviews gear for Backpacking Light.com, has written with clarity and authority on geometrical issues of tent design. See his blog essay “The Volumetric Efficiency of Trekking Pole Shelters.”

Related Content:

Recent One-person shelter reviews

- Six Moons Designs Lunar Solo

- REI Co-op Flash Air 1

- Tarptent Notch Li (2020 version)

- Big Agnes Scout 1 Platinum

Forum

- Looking for a cheap tent? Our community has some ideas…

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › Life in the Dog House: A Survey of the One-Person Tent, With History