A large, lazy cutthroat trout swings its hips, slow-swimming from the deep green waters towards my fly.

Upon its arrival to the surface, it stops short by half an inch and makes a slow quarter turn to get a better look.

And then swings a lazy 180 and swims back to the deep.

My heart is pounding. Time to try a different fly.

This feeling is the reason why I’ll go to almost any length to climb into the high alpine wilderness of the mountain west.

![]()

The summer heat in southeast Wyoming was starting to get the best of us. Lethargy inspired by high temperatures that were 10 degrees (F) above normal had us yearning for higher altitudes.

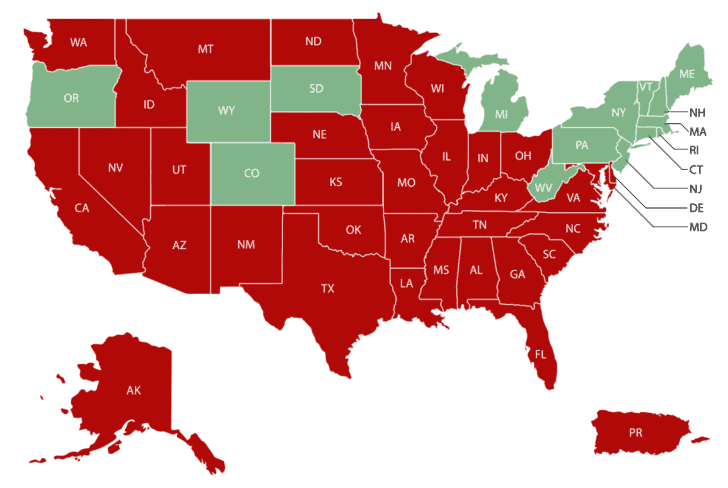

We had initially planned a trip south in the Colorado Rockies, but the coronavirus pandemic threw a wrench into those plans. Chase and I had to fly to Connecticut in a few weeks to move him into his new apartment there. We couldn’t take the risk that Connecticut would add Colorado (due to its increasing Covid-19 case counts) to the growing list of states from which travelers into CT would have to quarantine. Wyoming remained one of the few western states unlikely to be added to the CT travel advisory list, so we’d stay in Wyoming and seek higher elevation here.

![]()

We leave home in Laramie at 10 AM, and start our drive north through Rawlins, the Great Basin, Muddy Gap, and Jeffrey City.

We need to be back home in 56 hours.

Our destination: the Wind River Range.

![]()

On the drive, we plan our route.

We’d start at a trailhead popular among the locals, and hike a few miles on a maintained trail to an alpine lake for our first night. We figure an easy day would be good after a week of late nights and several hours of driving.

After passing through Lander, the southern gateway to the Wind Rivers, we check the map and begin our ascent up a switch-backed road into the foothills.

Shortly after the pavement ended, we meet a closed road-gate, still miles from our trailhead.

We get out of the truck and walk up to a laminated piece of paper with information about the closure due to road construction. No vehicles or ATVs. No bicycles. No hikers.

Ugh.

It’s already 3 PM, and we are running out of options, so it is back to the maps.

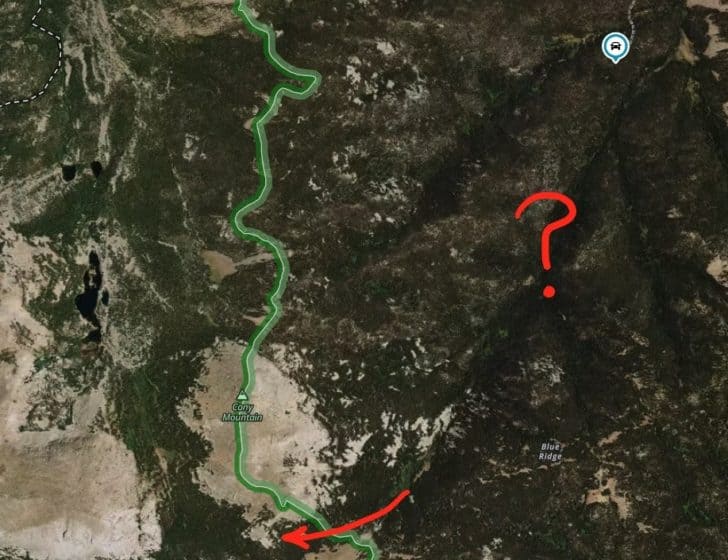

We finally pick a logging road that ends within three-and-a-half miles (as the crow flies) to the first lake in our canyon but found no beta whatsoever online about hiking in the creek drainage.

We knew it would be a bushwhack and that we’d climb a few thousand feet. But we are pretty good bushwhackers and highly motivated by tall tales of trout fishing in the alpine lakes above.

What we don’t consider, however, is that we weren’t crows.

![]()

I watch our trusty Tacoma’s odometer pass the 200,000-mile mark as we cross the North Platte River just west of Laramie. It’s a fitting celebration – a milestone achieved at one of the nation’s premier trout rivers en route to one of the nation’s premier alpine lake destinations.

But four hours later, as we rumble up Forest Service Road Number 304 at 8,800 feet (2,682 m), I feel nervous for the old girl and plead that her new struts will hold.

Our little forest road eventually turns into a rutted and rocky 4WD track. I slow to 5 mph as the rocks in the forest lane grow to diameters exceeding 18 inches.

In the middle of a creek crossing, we get stuck in the river sand, and I curse under my breath for not replacing the balding Duratracs sooner. But I switch to 4×4, rock back and forth, and we crawl out. In front of us, an impossibly steep hill climb. I’m not up for it, and I’m not up for putting her through it. She’s had a good run, and I back her into a wide spot in the road and shift to park.

We’ll take it from here, old girl.

I thank the old Tacoma for bringing us this far. We grab our packs, and walk up the remainder of the pseudo-road to its dead end in a lodgepole forest.

I take a compass bearing and start following an upward contour towards a nondescript ridge we need to cross before starting our descent into Sawmill Creek.

It’s a relatively open forest, and the travel is easy as we weave in and out of 60-year-old trees, stepping over the blowdowns of their siblings that lost the battle to the modern pine-beetle pandemic.

The skies darken, thunder booms overhead, and it starts to rain. I don’t worry too much about the weather, because like the crow, we have a destiny to fulfill.

![]()

In our first half-hour, we transition from the dry, open lodgepole forest to the lush greenery of the Sawmill Creek drainage.

My heart sinks a little. The forest understory in this valley is a tangled mess of blowdowns, currant bushes, swamps, and thick stands of young fir and spruce. Bushwhacking through this mess will take at least a couple of hours until we could break through to the more open whitebark pine forests that loomed at least a thousand feet higher.

And then, serendipitously, we noticed an open corridor through the forest, as far as the eye could see.

![]()

Lander, Wyoming is home to the world’s finest bakery, the National Outdoor Leadership School, Old Money, and the cemetery-interned cowboy who inspired the State of Wyoming logo. It’s also an old logging town.

The center of the area’s logging was in the Popo Agie River Valley in nearby Sinks Canyon. In the 1870s and 1880s, loggers ravaged the valley, and a handful of mountain sawmills were built in remote stream canyons of the Wind River Range, feeding into the Popo Agie River. One such operation was built in the Sawmill Creek drainage in the late 1800s, accessed by a crudely-built road suitable for a horse-drawn logging operation.

Member Exclusive

A Premium or Unlimited Membership* is required to view the rest of this article.

* A Basic Membership is required to view Member Q&A events

Home › Forums › Wind River Backpacking: Sawmills, Tenkara, and Trout in the Popo Agie Wilderness