Topic

Identifying geography based on map

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Home › Forums › General Forums › Philosophy & Technique › Identifying geography based on map

- This topic has 53 replies, 6 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 12 months ago by

Doug Coe.

Doug Coe.

-

AuthorPosts

-

Sep 11, 2019 at 8:42 pm #3609832

I’ve mentioned before that I am terribly navigationally challenged. I have taken a fairly rigorous course on wilderness navigation which helps in principle, but not so much in practice. I have been making it a point to keep a map and compass out on most of my on-trail trips just to practice. But I am having a really hard time looking at geography, looking at the map, and then figuring out what I’m looking at.

Most recently, I was going north on Trail 101 in the Sawtooth which is open at some places and partially forested in others. I was looking northeast and I saw a peak with my view partially obstructed by trees. I knew that it was either Ebert, Baron, or Baron North. Based on the trail we had covered, I didn’t think it was Ebert. To the west, I could also see one peak, which I thought was either Grandjean Peak or Tohobit Peak. I then triangulated where where I was on the trail using the mountains to the left and right of me . Needless to say, I was incredibly wrong and I had identified the wrong peaks and located myself around 2 miles off.

Are there any tricks to doing this? Any good ways to practice? I think the major challenge is that the angles change as you walk making the mountain look differently.

And I did have an altimeter, which was spot on. I know that’s an important part of navigation, but I feel that I should get the other parts down solid.

Sep 12, 2019 at 12:16 am #3609867One of the best things you can do is to make a habit of knowing where you are at all times. This requires looking at your paper map often and comparing it to obvious landmarks, changes in contour, changes in slope angle, changes in direction (compass), barometric altitude (can vary by hundreds of feet), crossing of streams and trail junctions, etc. Estimate your location on the map, then confirm with your cell phone or GPS. IMHO there’s no way around this – it takes time and actual practice in the field to get a good feel for how contour lines on a map correlate to what you see with your eyes.

Sep 12, 2019 at 12:28 am #3609872What Lester said. “This requires looking at your paper map often and comparing it to obvious landmarks, changes in contour, changes in slope angle, changes in direction (compass), barometric altitude (can vary by hundreds of feet), crossing of streams and trail junctions, etc. ” If using an altimeter on a multifunction watch, you need to calibrate it daily against a know reference.

Triangulation is a standard technique, but as you have learned, requires that you correctly ID the landmark. You also need to account for magnetic declination and the 3 to 4% error that any one hand held magnetic compass can have.

Sep 12, 2019 at 12:32 am #3609873Practice, practice, and practice.

It will come.Cheers

Sep 12, 2019 at 12:41 am #3609874Is there any practice that I could do when not in the wilderness? I don’t go as often as I’d like, so practice is reasonably rare. When I’m with a group, they do tend to get annoyed when I pull out the map and compass since it slows us down and the trail is quite obvious. I will usually do it during breaks.

Sep 12, 2019 at 1:46 am #3609883Maybe you could try a map that has shading in addition to the contour lines. The shading will make the terrain more obvious so maybe it’ll help your eye learn to associate the relief with the appearance of the contour lines? caltopo.com can add the shading, as can mytopo.com. Just a thought.

Sep 12, 2019 at 4:19 am #3609903Wear your compass on a string around your neck. Feel free to pull it out whenever you want to take a quick look. You do not have to be stationary for this. Start to associate the compass North with the sun position. Very often all I do is glance at the sun: elevation gives me time of day, and that with the sun position gives me approximate North. You do not need to be highly accurate in estimating North.\

Photocopy the relevant area of the topo map onto A4 paper (into B&W showing contours and creeks and roads) and carry that in a map case around your neck. Practice looking briefly at the map and mentally orienting it to North. Then try to relate that to the country around you. This too you can do while walking.

You need to be able to convert the contour lines into slopes in your head. I am sure there are web sites dedicated to teaching this. After a while you will be able to say to yourself that according to the map you should be heading West up onto a spur ahead, and looking around you will be able to identify the spur – and so on.

Good navigators do NOT rely on getting the map out after 4 hours of blind travel to try to work out where they are now. Instead they keeping a running image of the map in their head and keep updating their position at every minor point.

Mind you, this is not so easy when you are deep in the forest on flattish country!

Cheers

Sep 12, 2019 at 6:05 am #3609915“Start to associate the compass North with the sun position.”

Give or take a hemisphere, of course.

Sep 12, 2019 at 6:33 am #3609917Of course. I said ‘North’ because that is what one talks about with a compass.

Cheers

Sep 12, 2019 at 8:48 am #3609920Adam

If you’re serious about mastering land navigation I always recommend Lyle Brotherton’s “Ultimate Navigation Manual”. It’s a comprehensive course based on his work with Special Forces and SAR teams that’s full of practical advice and exercises. Work through this programme for a few months and you’ll become a confident and effective navigator.

(Forget about the Kindle version – the many diagrams are poorly reproduced. Get the paper version)

Sep 12, 2019 at 1:09 pm #3609937You are getting great advice listed above. There is a sport called Orienteering. I’m not sure where you are, but there are clubs in most areas of the USA where you can go to events. They have courses based on difficulty level. If you do competitive, the classes are then by age and sex. So as a 60+ year old male, I’m not competing against 18 year olds. My local club has meets during the school year. Starting in September and running into the first part of May. We have an event every few weeks. The places are state parks, scout ranches, city parks, national parks (LBJ National Grasslands, photo of that place is on our website) and private camps. It does require constant attention to what you are seeing around you versus the map you have. When orienteering, we do something called “thumb the map”. This means you always have your compass in your hand and one tip of it, is placed on the last thing you identified (Creek intersection, trail junction, hill….).

There are lots of great Orienteering web sites which have advice on best-practices.

Here is my local club website, click the “Get Better” for links to other resources

Sep 12, 2019 at 2:09 pm #3609940Great advice – thanks esp Geoff and Ray – really helpful information!

Sep 12, 2019 at 4:01 pm #3609948Roger—I should have added a smiley face. Just joking about how different it is down under, where-the-sun-is-wise. :)

Sep 12, 2019 at 6:18 pm #3609959Good navigators do NOT rely on getting the map out after 4 hours of blind travel to try to work out where they are now. Instead they keeping a running image of the map in their head and keep updating their position at every minor point.

Or they do what’s called “thumbing the map”. Fold the map such that the section on top is the section you are currently hiking through. Locate yourself on the map and put your thumb there. Make sure that your map is oriented so that “up” on the map is in the direction you are traveling. Now continue to walk while holding the map, even though your map hand is down at your side as you walk. Try to keep your thumb in the same place as you walk. The next time you look down at the map, you won’t have to spend time re-orienting yourself on the map. You should have moved some incremental distance along the trail under your thumb, depending on map scale, your rate of travel, etc.

Ray’s Orienteering recommendation is also excellent. I belong to the Southern Michigan Orienteering Club and do the same thing. SMOC does NOT break up the field for standard meets into age or sex categories. I think that only happens for the large competitive events, like the longer Rogaine events, etc.

http://attachpoint.org is a good place to start if you’re having a hard time identifying orienteering and/or adventure racing events near you.

Sep 12, 2019 at 7:21 pm #3609969You’ve gotten some great advice so far, especially from Lester and Roger. One thing not mentioned yet is map scale. A 1:24000 map will be much easier to micro-navigate with than say a 1:70000 scale map. Of course you may have to carry more maps depending on your trip, but it’s usually worth it. BTW, I don’t recommend shaded maps because when you flip them upside down or sideways they can look inverted.

To answer your other question: “Is there any practice that I could do when not in the wilderness?”. Yes! I do this all the time. Get a map of your local area and memorize it. Seriously. Start with a small area, then work bigger. Also, get a wrist or stop watch to time how long it takes you to cover various distances. When I go for walks around my town I pay attention to everything; What direction I’m going (always know where north is), how long I’ve been walking, where the sun is, what direction the wind is coming from, what plants grow where, which dogs to beware of, etc. When I get home I check what I remember against the map. It’s a fun exercise and will improve your powers of observation dramatically, which will really help when you’re out on the trail.

Another technique I use for learning and fun is to fire up Caltopo and Google Earth side by side and do some comparisons of the same area I’m going to hike or have hiked. The 3D in Google Earth isn’t perfect, but it’s fun and free.

Feb 1, 2020 at 9:38 pm #3629555I ordered Lyle Brotherton’s book, and it is quite good. One thing I’m struggling with is route planning. Brotherton talks about micronavigation, that is navigating to a target that may not be that far away, and then navigating to the next target, etc while taking the topography into account. For example, you may navigate to a gully, then go right and traverse along at a set altitude until you reach a flat clearing, and then head at some bearing up to a saddle. He talks about identifying landmarks in that would tell you that you got off course.

I like the idea because it allows you to always know where you are, but I’m finding it challenging to implement in reality. Imagine I’m going from point A to point B and ultimately to point C. Getting from point B to C seems fairly straightforward, but getting from A to B does not. Imagine there were no roads. How would you find your way with only a map and a compass?

Feb 2, 2020 at 12:15 am #3629567

Feb 2, 2020 at 12:15 am #3629567Well, that IS map&compass navigation. One probably cannot do it straight off the street: in the sort of country your map shows it would require some experience. But there is an old saying:

You avoid mistakes by experience

You get experience from mistakesThe route you show is not one I would ever attempt ab initio: it makes no sense (unless there really is an old 4WD track there). In the absence of any cleared track in that country I would navigate by using spurs and knolls, not by traversing. This is what has been done between B and C.

If there is a track there, I imagine the (dozer) driver just kept climbing at a ‘reasonable’ angle. Why he was there is another matter – logging maybe? I should warn you that old logging dozer drivers are known to have been start raving mad at times. He could of course simply turn his machine around and come back down at any time.

So, your example is not realistic. If walkers do go from A to B it will be because there IS a track there.

Cheers

Feb 2, 2020 at 5:51 am #3629574OK, “Identifying Geography Based on a Map”….

This trip is basically following the Newport Creek drainage up to Hex Peak at the top of the drainage.

The A-B-C route starts at about 2380 ft and ends at 5034, a gain of 2654 ft over 5-6 miles. It is not a particularly rewarding hike because you are in the trees until you get to Hex Peak.

Finding the start point is not particularly easy. Use your odometer to find and cross Newport Creek (if coming from the south), then go 1/4 mile and find Point A. If coming from the north, cross Newport Creek, then turn around and find point A.

The road from point A is pretty steep, and it goes up a bit of a draw. You can see this because the slightly wavy topo lines head up hill.

The terrain is ok once you reach the top of this little draw. After the old road to the left, which you may not see, the road is pretty flat. The road bends 90 degrees to the right, and after that it is very steep and crosses a steep slope to point B. When the road bends 90 degrees left you are close to point B. Look for the trail to the right. The trail is going to pretty much follow the ridgeline to Hex Peak. The trail crosses a bit below Hex Mountain. Your best view is the from the bare ground just past Hex Mtn, close to the trail junction.

Feb 2, 2020 at 10:24 pm #3629660One of the things that helped me when I was first getting into hiking and backpacking in college, was during breaks, I would always lay out my map and orient it correctly (N on map was pointing N) so I could see it in relation to the landmarks around me on the trail so I usually had an idea where I was in what I was seeing which helped me keep track of where I was hiking later. Stopping for those breaks near a marked trail junction so you know where you are on the map, helped place me on that map and made it easier to identify those peaks around me.

Feb 3, 2020 at 8:35 am #3629689I guess I wasn’t clear. In this made up scenario, you magically teleport to point A. Then you need to get to point B crosscountry. There are no roads in this scenario.

I can see using Newport Creek as a handrail and walking next to it. But at 2800 feet, it gets cliffy so I don’t think you’d be able to go much farther. From there, it’s not entirely obvious how to reliably get to point B.

In reality, there are roads and the route is quite trafficked and fairly straightforward. Views are surprisingly good.

Feb 3, 2020 at 1:18 pm #3629717using Newport Creek as a handrail and walking next to it.

I don’t know what the scrub is like there, but in Oz that would be he last thing you would do. Very slow!Cheers

Feb 5, 2020 at 9:58 am #3629967Adam I’m not sure I understand exactly what you are asking. The question(s) may be difficult to frame on a complex subject but questions are always good. The Prophet Amos said something like “The wise man seeks council”

The Cherokee pretty much always followed the ridge lines when they wanted to get somewhere in a hurry; and if there weren’t some really deep pass with nice wide valleys on both sides. The AT from about Harper’s Ferry south probably basically follows a series of Native American trails.

Following a drainage is usually problematical because of the typically steeper terrain (left/right and up/down, water follows the quickest path) and heavier vegetation; not to mention the sudden transitions that give us those lovely waterfalls and the need quite often to cross and re-cross the drainage (wet- maybe dangerous) because of steep obstacles (anything higher than about 8 feet can often be impassable – think pour-offs in the desert southwest) Plus wet slippery footing. Elisha Mitchell the geologist for whom Mt. Mitchell, the highest point east of the Black Hills is named; died from loosing his footing and slipping over a waterfall on the slopes of that mountain.

The book mentioned by Geoff should acquaint you with all the geometry/math and technique.

A general rule of thumb might be that you extend the distance between contour line crossings as much as practical. You also avoid spots where the contour lines are close together! Following this “rule” you pretty much end up with the road in your example. You’ll note that in the steep lowest part it runs parallel beside the tighter contour lines for the unavoidably steep lower very first part until crossing them at right angles. Those types of contour lines where the line runs roughly perpendicular to the fall line to a “V”turn tend to follow the easiest grade. The road then sort of parallels the contour lines as they widen and run parallel to the slope until again it’s forced to cross going up. Once the route gets near enough to B it follows the ridgeline from B to C which also follows the rule. Maybe another generalization would be that its good to go parallel to contour lines wherever or whenever possible but it also helps to have the ground under each foot basically about the same level which is why ridges are better than side-slopes.

Of course vegetation, fire and flood damage and fun stuff like Talus can change the route calculation. Nothing like a laurel hell or an alder thicket to make things interesting.

There are lots of good comments copied upthread and I really like this one from Paul:

“Another technique I use for learning and fun is to fire up Caltopo and Google Earth side by side and do some comparisons of the same area I’m going to hike or have hiked. The 3D in Google Earth isn’t perfect, but it’s fun and free.”

Like Paul I’ve found that looking back over terrain I’ve covered on foot (and from the virtual air in 3-D!)can really help to put everything into perspective. This can really help those maps take on a 3-D shape.

And like pretty much everyone I agree that practice makes perfect; or good enough until perfect comes along.

Feb 5, 2020 at 11:11 am #3629981Let me try to explain again. Let’s say you want to bag Hex Mountain, starting a point A. For this scenario, it doesn’t matter how you get to point A. You got there somehow, and you know that you are precisely there.

You look at the map. It’s very clear to you that once you get to point B, you’re good to go. Navigation is quite straightforward from there.

The challenging part is getting from point A to point B. Unfortunately, you realize that it’s all cross country travel and there are no roads to guide you. I know the map shows roads, but your cartographer friend who works with the Forest Service tells you that those roads were never built because they ran out of money. Otherwise the map is correct. Unfortunately, an intern printed up the map and added them anticipating that they would build the roads, but it never happened. They also ran out of money to print new maps. Whoops. In reality, this would be quite unlikely, but this is a hypothetical scenario.

One way to do this would be to follow a bearing the entire way from point A to point B. Although there are techniques to do this where you follow this bearing to an intermediate landmark, in reality, this is incredibly slow going especially if you run into any obstructions such as downed trees.

You thus realize that you need to plan a different route. You realize that the best thing to do is break up the trip from point A to point B into smaller legs that may not be the most direct route there. This may be following a bearing for a short distance or following geographic features. After each leg, ideally you’d end up at a place where you’d mostly know where you are, and you’d plan the next leg from there. For example, you might be at a certain altitude at the base of a gully, or on top of a small prominence.

My question is: what would be your planned route and why?

Feb 5, 2020 at 2:15 pm #3630008Well I can copy part of my evidently rambling discourse from above

- A general rule of thumb might be that you extend the distance between contour line crossings as much as practical.

- Those types of contour lines where the line runs roughly perpendicular to the fall line to a “V”turn tend to follow the easiest grade

- Maybe another generalization would be that its good to go parallel to contour lines wherever or whenever possible

- it also helps to have the ground under each foot basically about the same level which is why ridges are better than side-slopes.

- And another: If there is a wide space between contour lines that can indicate a flatter ledgy stretch. Try to incorporate those into your route where possible.

Here’s an example of a problem from the Great Smokies Mts. There is still an existing trail to the McGee Springs Campsite which is on the right of the map. The spot on the top left is called the Big Pool and it’s where the 3 forks of Raven Creek come together to form Raven Creek proper. There used to be a trail from McGee Springs to the Big Pool but it is no longer maintained and doesn’t show on the mapbuilder topo. The elevation drop is severe. The vegetation is intense with pockets of laurel hells. How would you get to the Big Pool? BTW There is an easy way to cheat on this one.

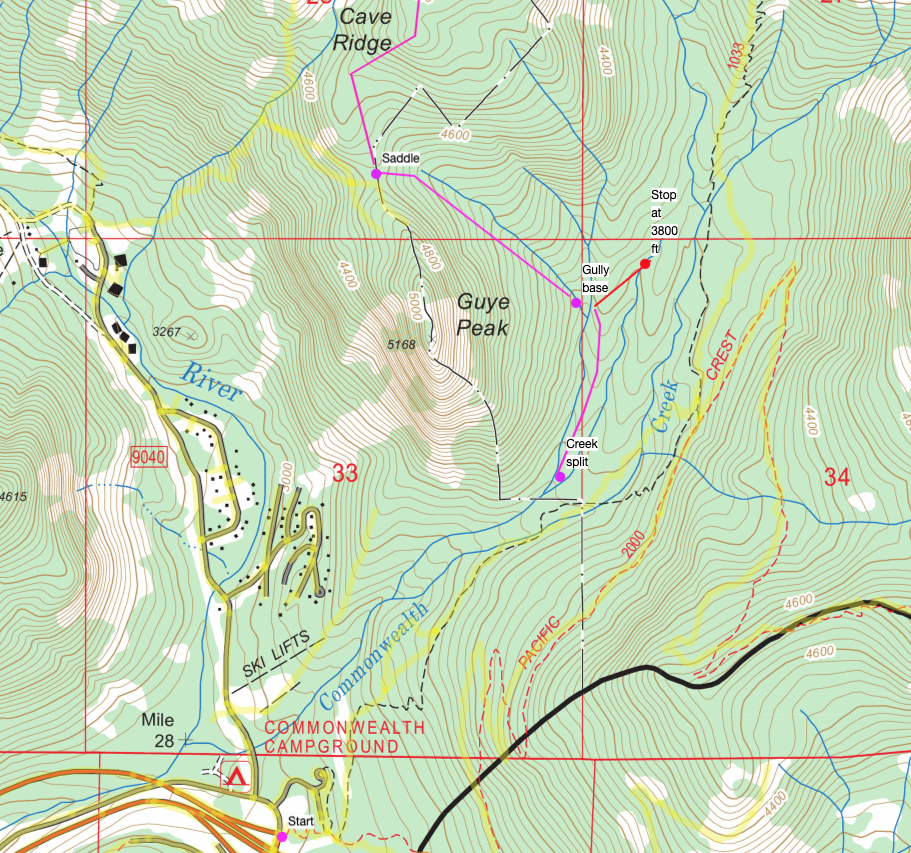

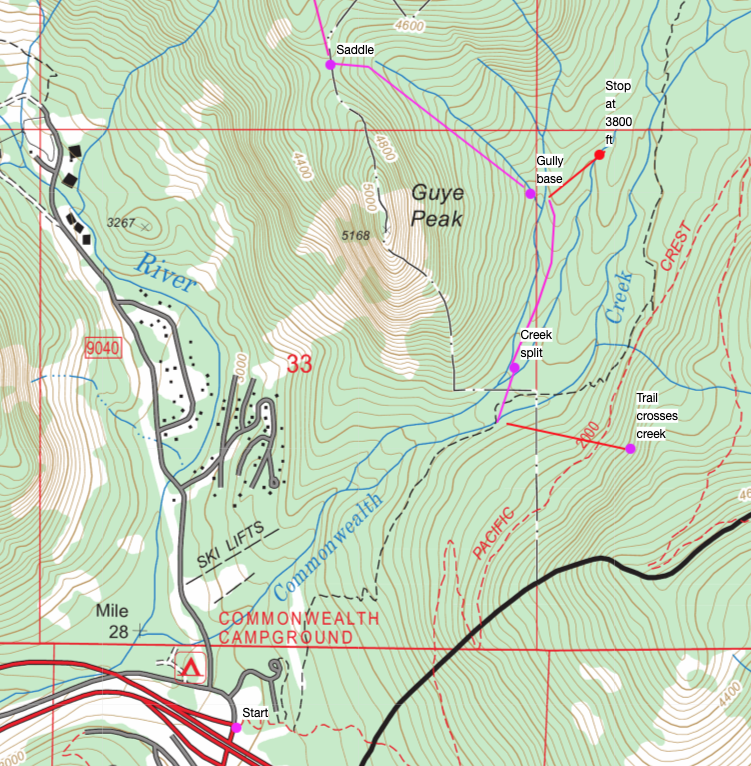

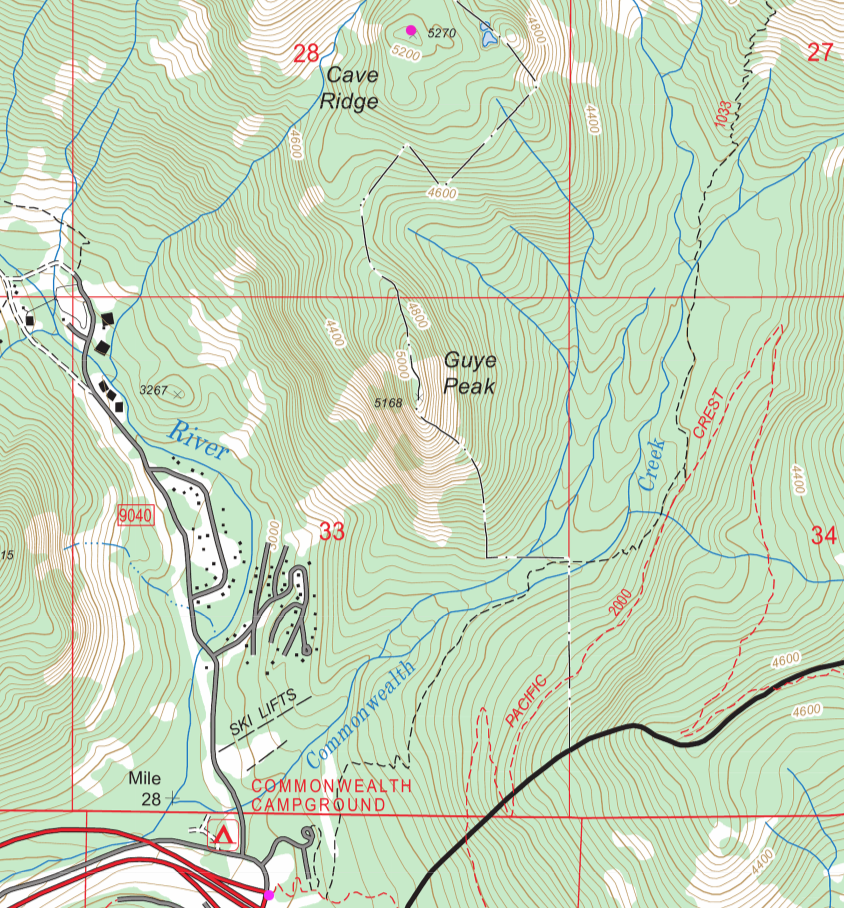

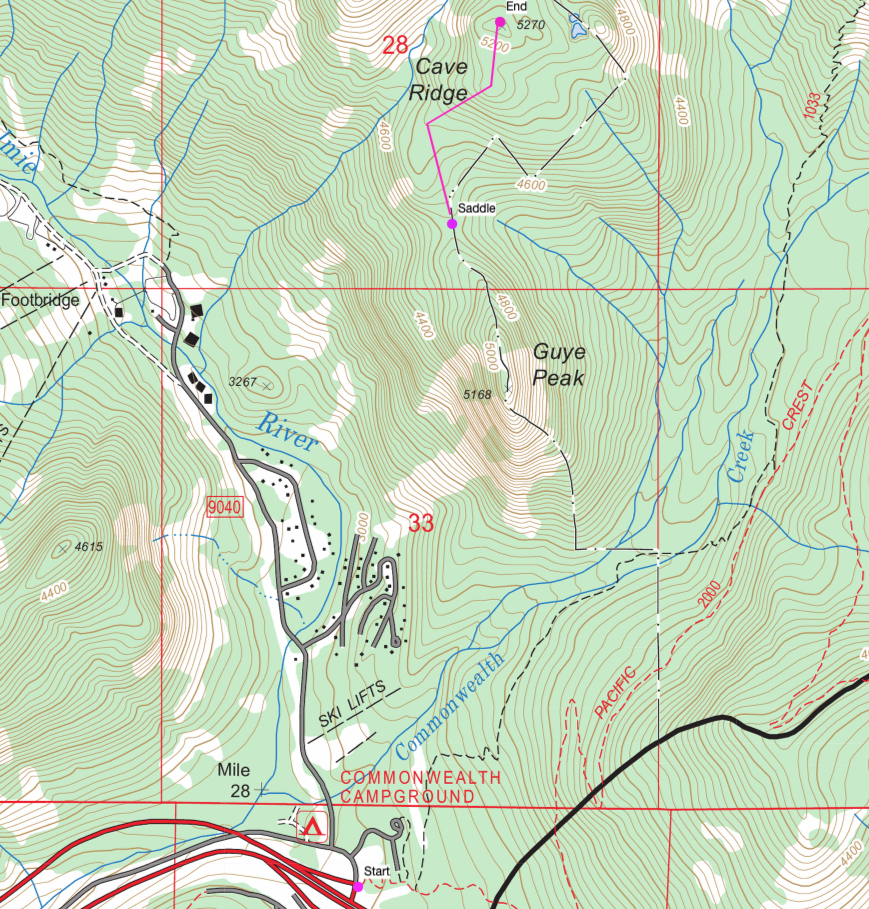

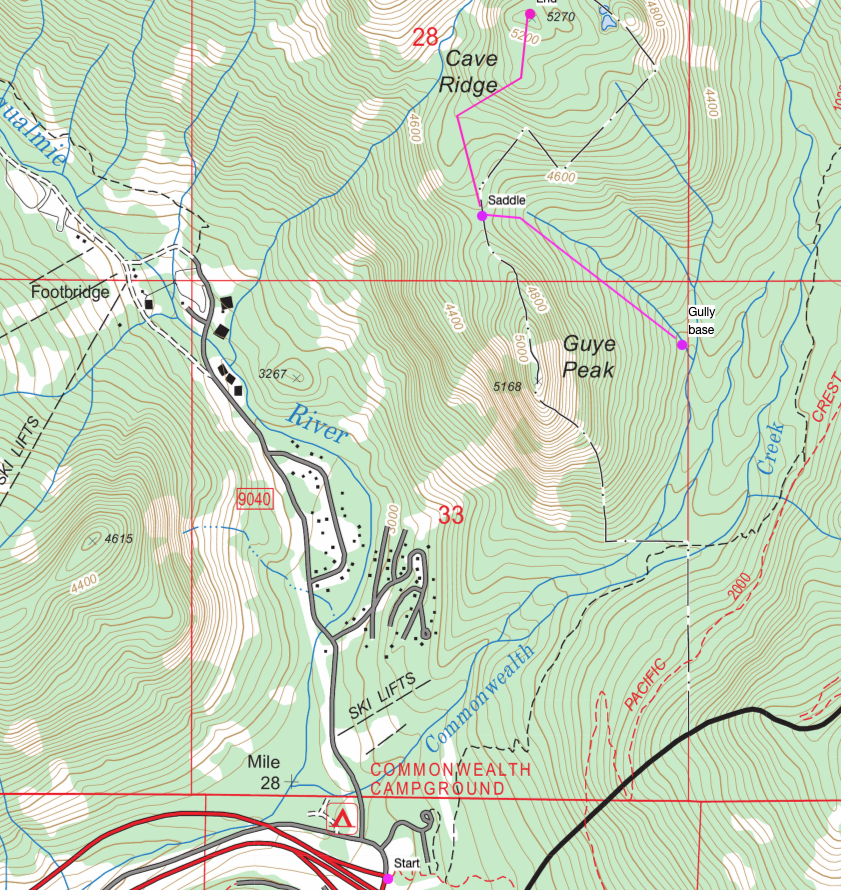

Feb 5, 2020 at 2:18 pm #3630011So here’s an example of trip planning detail for Hex that I’m looking for.

So you want to start at the trailhead and end up on the top of Cave Ridge. Obviously doing this as the crow flies is a bad idea.

The first thing I realize is that it is best reached by the saddle between Cave Ridge and Guye Peak. From there, it seems straightforward to take a bearing / follow geography up.

So now the issue is how to get up to the saddle. There is a nice gully to take me up.

Finding the gully is a bit trickier. You can follow the northernmost creek from the split in the two creeks. Hopefully, this is obvious, but may not be so if there is little water flowing. You find the next split and you are where you are, around 3800 ft. If you continue and hit the second split of the creek, the bearing up the slope is quite different, and it’s a bit higher in elevation.

Finding the gully is a bit trickier. You can follow the northernmost creek from the split in the two creeks. Hopefully, this is obvious, but may not be so if there is little water flowing. You find the next split and you are where you are, around 3800 ft. If you continue and hit the second split of the creek, the bearing up the slope is quite different, and it’s a bit higher in elevation.When this is snow-covered, this is even trickier, so maybe I would rely on the bearing up the slope plus the altitude?

Finally, getting to that junction is fairly straighforward. You go until the trail crosses the creek.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

HAPPENING RIGHT NOW (February 11-21, 2025) - Shop Hyperlite Mountain Gear's Biggest Sale of the Year:

Our Community Posts are Moderated

Backpacking Light community posts are moderated and here to foster helpful and positive discussions about lightweight backpacking. Please be mindful of our values and boundaries and review our Community Guidelines prior to posting.

Get the Newsletter

Gear Research & Discovery Tools

- Browse our curated Gear Shop

- See the latest Gear Deals and Sales

- Our Recommendations

- Search for Gear on Sale with the Gear Finder

- Used Gear Swap

- Member Gear Reviews and BPL Gear Review Articles

- Browse by Gear Type or Brand.

Finding the gully is a bit trickier. You can follow the northernmost creek from the split in the two creeks. Hopefully, this is obvious, but may not be so if there is little water flowing. You find the next split and you are where you are, around 3800 ft. If you continue and hit the second split of the creek, the bearing up the slope is quite different, and it’s a bit higher in elevation.

Finding the gully is a bit trickier. You can follow the northernmost creek from the split in the two creeks. Hopefully, this is obvious, but may not be so if there is little water flowing. You find the next split and you are where you are, around 3800 ft. If you continue and hit the second split of the creek, the bearing up the slope is quite different, and it’s a bit higher in elevation.