Editor’s Note: This is the first essay in a three-part series. Check out part two here. and part three (video) here.

Introduction

What is the future of backpacking in an era of frequent massive wildfires? This year’s giant blazes in the Western U.S. closed many thousands of square miles (tens of thousands of square kilometers) in forests and parks for weeks and months. While the backcountry burned, land managers couldn’t take any chances that trekkers might start new fires or need rescue. This year, helicopters plucked dozens of backpackers from the Sierra Nevada when rapidly spreading blazes broke out. And in Colorado, choppers rescued two dogs and 23 hikers when a relatively small fire blocked a trailhead.

Most experts expect wildfires to get larger and more frequent, which will significantly impact backpackers in ways that you might not have considered. Learning to work around massive wildfires will become yet another non-traditional backpacking skill in the western U.S. and other countries. This essay gives you some background on wildfires in the U.S., describes the potential health and safety risks, and suggests how to stay safer and healthier. The next essay in this series (to be published on Friday, October 3oth) will cover landscape changes, potential new rules for enjoying the backcountry, and adapting to a flame-filled future.

It’s important to keep things in perspective when we’re talking about the health and safety of millions of people affected by wildfires and smoke. The recreational longings of backpackers are low priority compared to the lives and health of people and landscapes.

Background

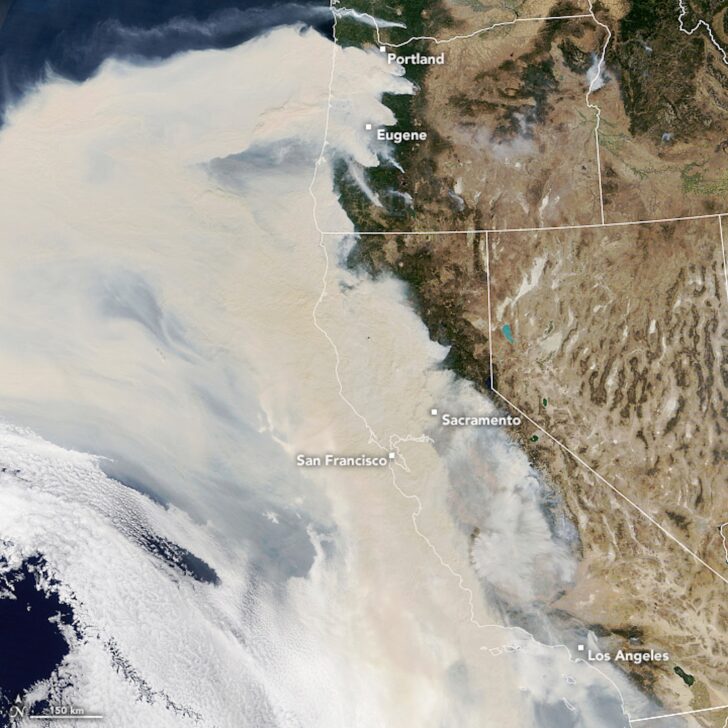

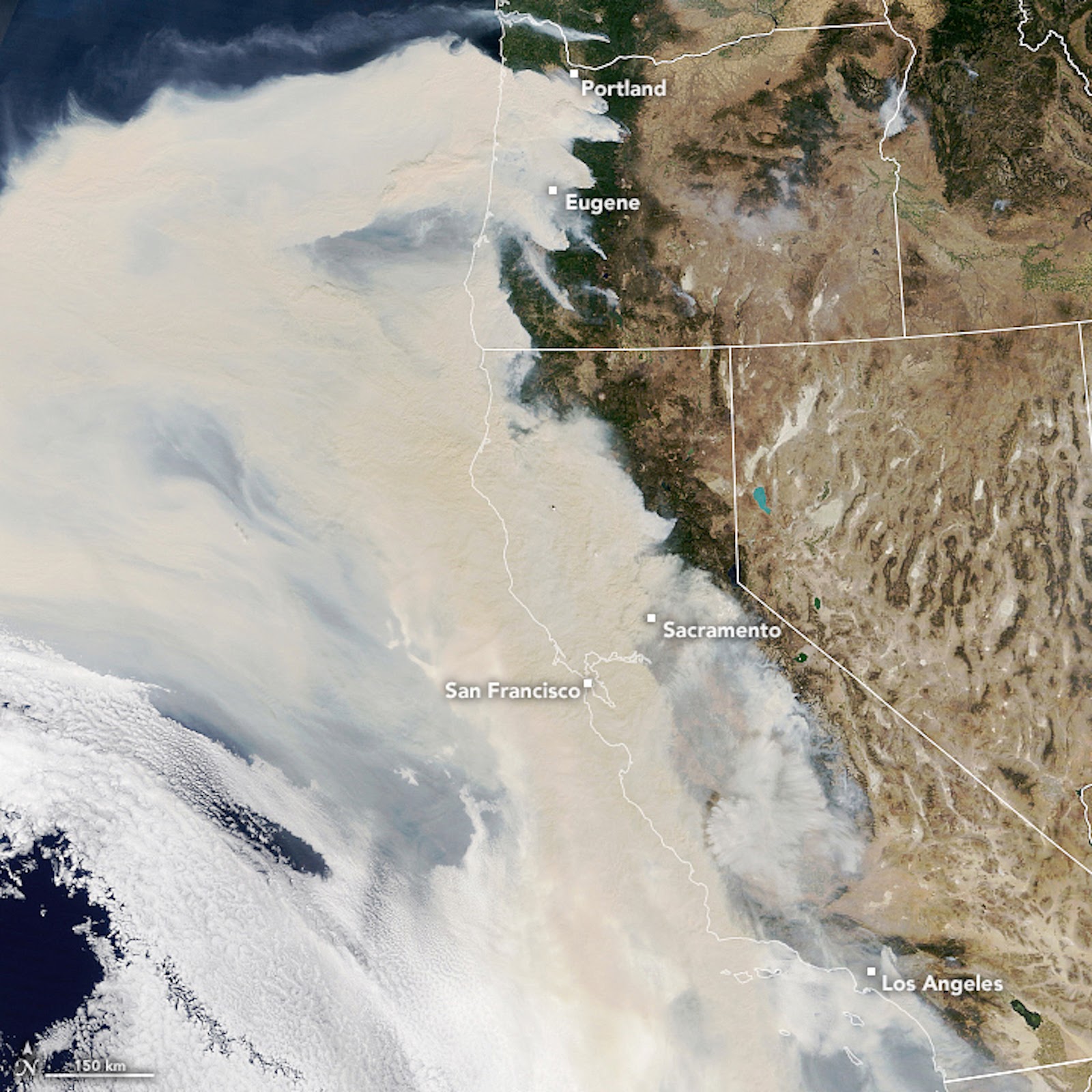

U.S. firefighters call wildfires “massive” or “megafires” when they reach more than 100,000 acres (156 mi², 404 km2). In 2020 alone, California suffered from ten massive wildfires, including its first modern “gigafire” over 1 million acres (1,560 mi², 4,040 km2) – the August Complex.

And the Creek Fire in the central Sierra Nevada virtually exploded one night, torching another 100 mi² (260 km2) and triggering heroic military helicopter evacuations of trapped campers and backpackers. A few of this year’s fires burned for weeks in the so-called “asbestos forests” on California’s foggy, damp north coast. For months, tens of millions of Golden State residents suffered from unhealthy levels of wildfire smoke.

Megafires also broke out in Colorado, Wyoming, and Oregon. The Cameron Peak Fire has grown to the largest in Colorado’s modern history, eclipsing a record set by a different wildfire just seven weeks earlier. In the past year, Australia burned an astronomical area, more than five times the U.S. total in 2020. And record-breaking swaths of Russian Siberia burned this year after smashing records less than 12 months earlier.

Recent Wildfire Sizes

| Country | Year | Square miles | Square km | Similar size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 2019-2020 | 72,000 | 186,000 | North Dakota |

| Russia | 2020 | 54,000 | 140,000 | Nepal |

| Russia | 2019 | 50,000 | 131,000 | Greece |

| Canada | 2014 | 17,600 | 45,600 | Slovakia |

| Canada | 2013 | 16,200 | 42,100 | Denmark |

| U.S. | 2015 | 15,800 | 41,000 | NH + MA |

| U.S. | 2020 | 13,000 | 33,700 | NH + CT |

| Brazil | 2020 | 7,800 | 20,000 | El Salvador |

| Portugal | 2017 | 2,000 | 5,000 | 6% of country |

Totals as of October 17, 2020. Sources: news reports, Wikipedia, Canada National Forestry Database, and U.S. National Interagency Fire Center.

Wildfires don’t just ravage iconic forests. I grew up watching Southern California’s chaparral-covered hillsides burn with regularity. In college, I learned that some of those bushes and trees depend on frequent fires for reproduction. Many of the same mountains and canyons burned again this year. Fires also raced through sagebrush in eastern Washington state, wiping out one of three small populations of a very endangered pygmy rabbit.

In too many cases this year, firefighters ran out of resources and defended carefully chosen towns and homes while letting large areas burn. The U.S. could expand wildland firefighting capabilities by a factor of 10 and still not have enough for years like this.

You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet

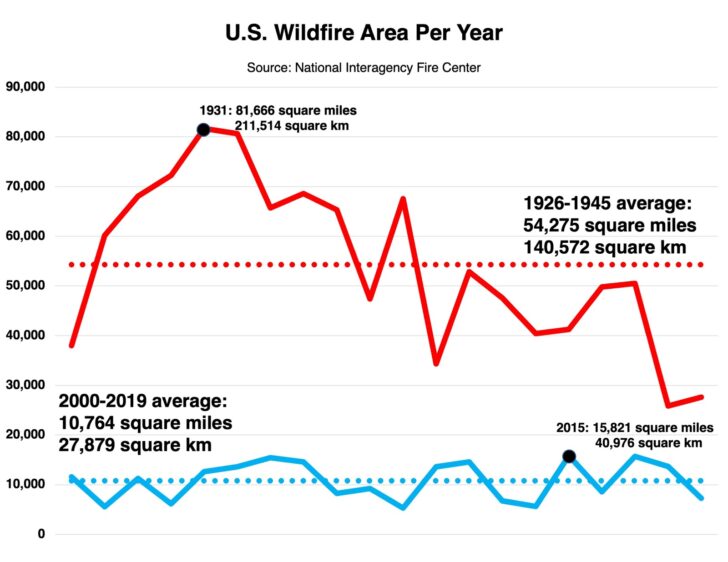

This year we’re experiencing fire activity that some forecasts claimed might happen 30 years in the future – yet we could see a rerun every couple of years. But in the U.S., we haven’t even reached the fire totals of the early 20th century.

Scientific studies project longer fire seasons, more fires, and bigger fires worldwide. Our new wildfire era has many causes and many potential solutions. But for this article, I’ll focus on backpacking safety and health risks and what you might do to reduce them.

Immediate Dangers

If you are backpacking far from civilization when a wildfire breaks out nearby, you don’t have many options. Even finding out that a large blaze is headed your way might be impossible. Consider these suggestions to reduce your risk.

- Before your trip, check on wildfire and weather forecasts. Even if red flag warnings aren’t posted, any predictions of hot, dry, windy conditions dramatically increase fire likelihood. Look over your planned path and work out possible escape routes. If you have cell coverage or a satellite communicator, check on conditions daily, with the assistance of trusted home contacts if needed. Consider modifying your trip to make fleeing easier. Or change the dates or location of your trip.

- If evacuation looks likely, pack quickly and leave immediately. Don’t delay hoping the fire might change direction at the last minute – that’s probably too late. Take the shortest route to safety, even if that means you exit hundreds of miles from your car – you’ll figure it out. Let emergency contacts at home know of your changed plans as soon as possible.

- Finally, despite your best efforts, a wildfire might trap you. Pushing the SOS button on your PLB or satellite communicator is totally appropriate – but don’t expect a quick, miraculous rescue. You must fend for yourself until help arrives or you escape under your own power.

- A backpacking shelter won’t protect you from choking smoke, falling trees, and raging flames. If threatened by fire, head for an open area with as little vegetation as possible, ideally next to a lake or river where you could submerge. This year’s fires yielded several stories of trapped people surviving in the water, with their nose and lips barely exposed to falling embers and thick smoke. Find a stable spot where the river won’t sweep you downstream if you lose grip on the rocks or vegetation.

Short-term Smoke Impacts

Scientists have found more than 100 chemical compounds in wildfire smoke and suspect many more. Its composition changes depending on fire intensity, time of day, and fuels like trees, brush, or buildings. Modern structures and furniture contain various potentially toxic and carcinogenic burnable materials, including plastics, furniture, cleaners, and pesticides.

And smoke can still be hazardous hundreds or thousands of miles (kilometers) downwind. You might be backpacking several states away from a blaze and still suffer.

Wildfire smoke can cause a lot of problems quickly. Visibility might drop so low that navigation or even trail walking becomes almost impossible. Plus, your eyes are likely to burn, itch, and make tears.

You will probably cough a lot – that’s normal and good for you. Smoke could also trigger asthma or other lung conditions. Even a short exposure to wildfire smoke can temporarily increase your risk of stroke and heart attack. Studies show that emergency room visits jump 10% or more after smoky air arrives. And if you are close enough to flames or smoldering stumps, carbon monoxide poisoning can make you woozy or kill you.

Wildfire smoke can be a severe problem for people with asthma, bronchitis, COPD, diabetes, and chronic heart disease. Children, pregnant adults, and elders are especially sensitive.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says:

“Wildfire smoke is a mix of gases and fine particles from burning vegetation, building materials, and other materials. Wildfire smoke can make anyone sick. Even a healthy person can get sick if there is enough smoke in the air. Breathing in smoke can have immediate health effects, including:

- Coughing

- Trouble breathing normally

- Stinging eyes

- A scratchy throat

- Runny nose

- Irritated sinuses

- Wheezing and shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Headaches”

Long-term Smoke Impacts

When you inhale microscopic smoke particles, your lungs absorb some of them. Then your body attacks them like viruses or bacteria. Except that these foreign specks don’t break down as quickly, so your immune system stays highly inflamed longer – which affects everything else in your body.

Researchers suspect links to lower birth weights, damage to organs including the lungs, heart, liver, kidneys, and brain; and more susceptibility to diseases like COVID-19. In one study, summer exposure to wildfire smoke caused flu cases to jump three to five times higher the next winter. A news story described wildfire smoke as “like tobacco, without the nicotine.”

Is it Safe?

This summer, many of us constantly refreshed web sites like PurpleAir.com and fire.airnow.gov, watching as PM2.5 values moved up and down with smoke levels. These pages even displayed color-coded dots indicating health risks based on short-term studies. As we just learned, the long-term effects are mostly unknown.

Researchers can’t definitively answer the question, “Is it safe to go backpacking when it’s smoky?”

They do know this: more smoke is worse, prolonged exposure is worse, and vigorous exercise makes everything worse. One scientist’s rule of thumb: stay inside if you smell smoke or the sky is orange.

Changes for Health and Safety

Here are some suggestions on how backpackers can stay safer and healthier in this new era of wildfires. Also, the Pacific Crest Trail Association (PCTA) posted excellent advice on burn area safety for all hikers.

- Escape route planning should become part of your pre-trip process. Spending a few minutes at home considering your options will be much better than scrutinizing maps in a semi-panicked state under orange, smoke-filled skies, with flames cresting over the ridge.

- If wildfire smoke is thick, but flames don’t threaten, your best option might be to stay put until the haze clears. If you have asthma or other lung problems, use your inhaler and medications as directed. Move to cleaner backcountry air when and where you can.

- We’ve become all too familiar with face masks in 2020. You might want to take a lightweight, vented N95 mask to filter wildfire smoke – simple coronavirus masks won’t help much.

- If you are already deep in the backcountry when the smoke blows in, you could reduce your activities and stay put until it blows out again. That might not be practical, depending on your location and supplies. Do your best to reduce smoke exposure.

- Hats, glasses, and sunglasses might keep ashes out of your eyes – a little. Stay well-hydrated to assist coughing when the smoke is thick. Wear a wet bandana or neck gaiter over your mouth and nose – it might help.

- You could rethink trip timing, backpacking less during wildfire season, and more in the formerly colder and wetter months. In much of Southern California and similar regions where wildfires are a year-round problem, that might mean going elsewhere.

- If you are in a sensitive health group – pregnant, older, or with pre-existing health conditions – reconsider plans to trek in the backcountry when fire and smoke risks are high.

Conclusion

More frequent massive wildfires producing choking smoke seem to be the new normal. These blazes present increasing health and safety concerns for backpackers. But you can take steps to reduce your risks.

Were you trapped by a wildfire while backpacking? Have you suffered from too much forest fire smoke in the backcountry? What did you do to stay safe and healthy? Share your experiences below so we can all learn.

More Information

2020 Western United States wildfire season, Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_Western_United_States_wildfire_season

An irregularly updated overview of this historically wimpy fire season.

Can New Research Help Reduce the Impact of Wildfires? Governing

https://www.governing.com/now/Can-New-Research-Help-Reduce-the-Impact-of-Wildfires.html

Much of what we are told about wildfires and forest management is wrong, according to peer-reviewed scientific research. Highly recommended.

Wildfire Smoke, CDC

https://www.cdc.gov/disasters/wildfires/smoke.html

How breathing in wildfire smoke affects the body, National Geographic

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/09/how-breathing-wildfire-smoke-affects-the-body/

How bad is all that wildfire smoke to our long-term health? ‘Frankly, we don’t really know’, Los Angeles Times

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-09-19/california-fire-smoke-health-risks

Three clear explanations of what little we know about the effects of wildfire smoke on the human body, plus tips on protecting yourself.

Unsafe to drink: Wildfires threaten rural towns with tainted water, CalMatters

https://calmatters.org/environment/2020/10/california-wildfires-unsafe-drinking-water/

Reports on seriously contaminated rural water systems after California wildfires.

Related Content

More By Rex Sanders

- GPS – The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

- Standards Watch: Sleeping Bag Temperature Ratings

- Improving R-Values for Consumers

In the Forums

- Our community discusses the 2020 wildfire season.

Skills

- Check out our three-part series on dealing with wildfires while backpacking.

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › Adapting to Changing Wildfires: Part One