Editor’s Note: This is the second essay in a three-part series. Check out part one here and part three (video) here.

Introduction

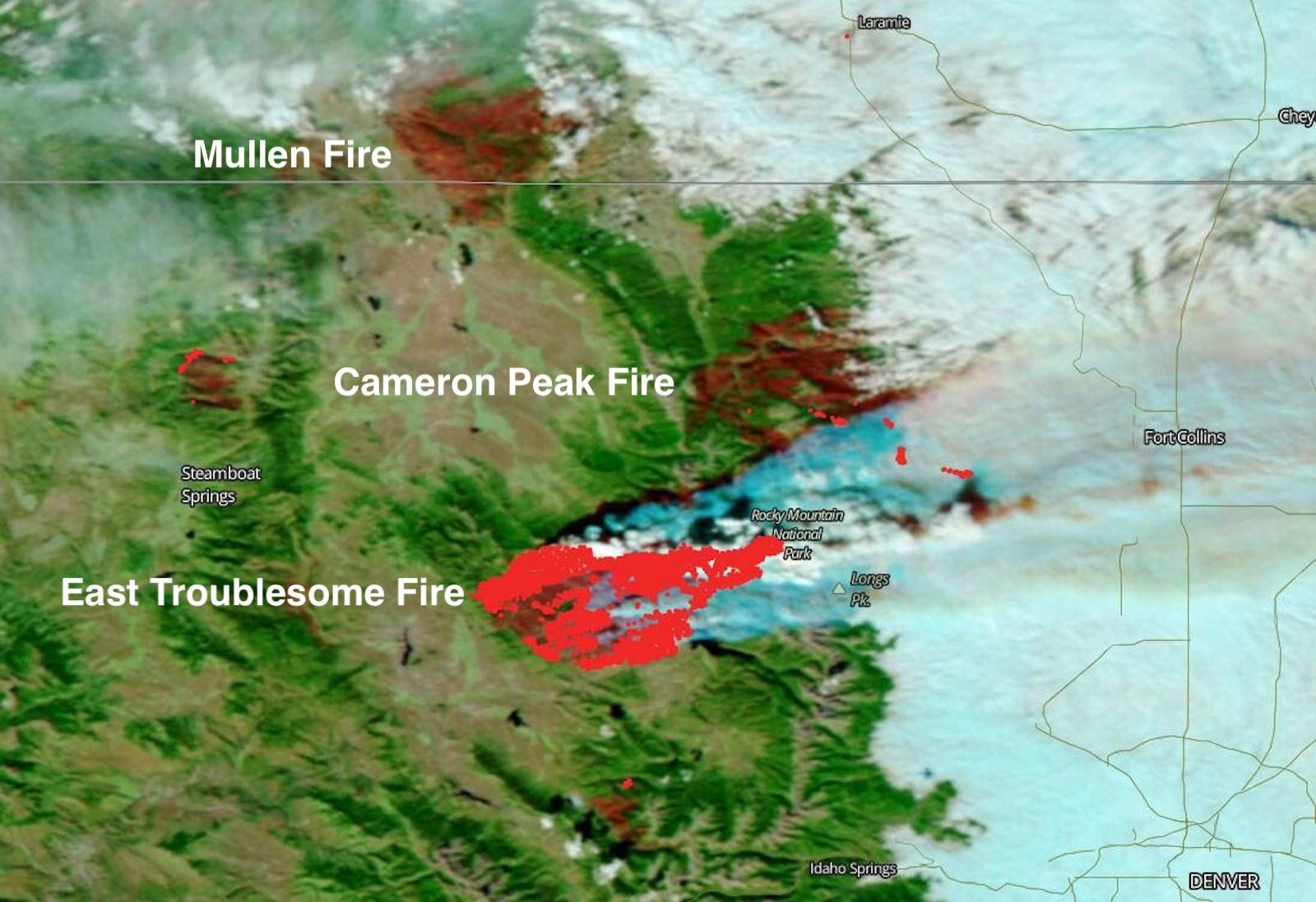

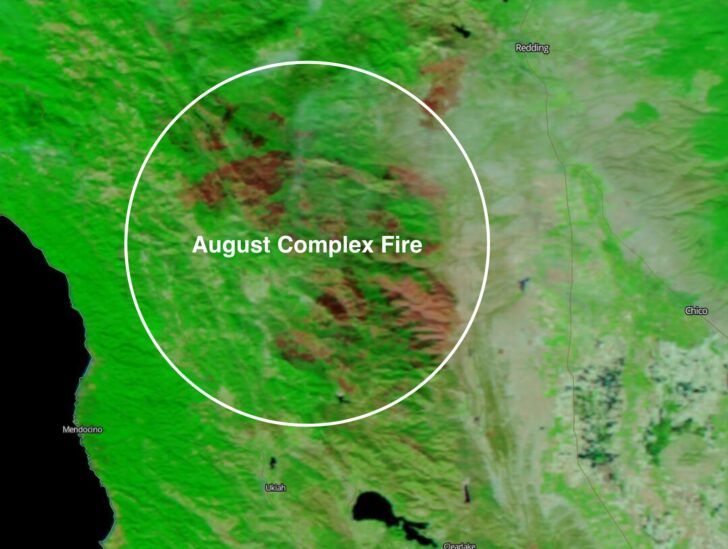

Wildfires in western North America have changed for the worse and will continue changing. Fire tornadoes ripped living trees out of the ground, set them alight, and dropped them miles away. Blazes consumed 400 mi² (1,000 km²) in one day. Researchers compared the worst wildfires to the firebombing of Dresden in World War II or Hiroshima’s destruction by an atomic bomb.

Existing fire forecasting software has proven useless, while scientists struggle to develop new models. Some researchers predict that, on average, next year will be worse than the year before – indefinitely. As Daniel Duane wrote in WIRED, “It is as if we’ve crossed some threshold of climate and fire fuel into an era of uncontrollable conflagrations.”

While reasonably cautious backpackers are unlikely to perish in wildfires, we must learn to live with altered fire behavior, landscapes, and rules. This essay is an exploration of what some of those changes might look like.

Closures

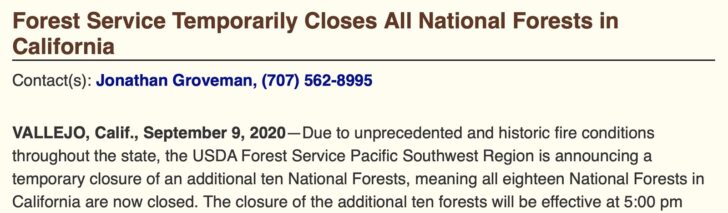

During active wildfires or even high-fire-danger weather, land managers will close parks and forests for many good reasons. Don’t try to sneak in, thinking you know better. You are probably interfering with firefighting just driving to the trailhead, and you could put others at grave risk if you need rescue.

For several weeks in 2020, every National Forest and BLM area, most National Parks, and many state and local parks in California closed to backpackers and all other recreational users.

Even after authorities declare a fire contained – with fire lines surrounding the blaze – trees and brush could continue burning until the first heavy rains or snowfalls. Wildfires sometimes jump artificial boundaries. Remnant fires can produce a lot of smoke; many trails are trashed; falling rocks, limbs, and trees could trap or injure you; and long-smoldering ash pits that look like solid ground could severely injure you.

Some parks and forests might stay closed for months or years after the immediate dangers subside. Land managers must fix problems like blocked or collapsed roads and trails, damaged or destroyed buildings, and broken or polluted water sources.

Short-term Landscape Changes

Species Adaptation (Or Not)

Wildfires do not create uniform destruction. Within a blaze’s boundary, we often see a mosaic of unburned, lightly burned, heavily burned, and nothing-but-ashes areas. This variety is fortunate because plants and animals in the less-affected parts can repopulate the heavily-damaged zones, sometimes quickly. And we often witness an explosion of rarely seen species that thrive in post-wildfire conditions, including open spaces, abundant sunlight, and mineralized soil.

But it doesn’t always work that way. Rare and endangered species populations can plummet or vanish. Wildlife may disappear temporarily or permanently. Trees and brush will be damaged or killed. Formerly postcard-worthy vistas often look like moonscapes.

Water Problems

Fires can expose rivers, lakes, and watersheds to more sun, dramatically reducing water levels in the short run. Many blazes leave behind blackened ponds and streams filled with ash, burned debris, or landslides. Developed water sources might suffer from destroyed spring boxes, burnt piping, damaged tanks, and melted spigots.

Toxic or cancer-causing chemicals from fires and smoke can make water in wildfire areas and downstream unusable, even for washing. One rural system found benzene levels 40,000 times higher than EPA standards after a fire. You could experience serious challenges finding drinkable water, even from previously-reliable sources.

Trail Damage

Trails can suffer severe damage during wildfires, caused by erosion from firefighting work, collapsed retaining walls, rockslides and landslides, fallen trees, and even stealthy 2,000 F (1,000 C) ash pits. Trail signs may be down and pointing the wrong way or reduced to slag and ashes.

With trail maintenance funds often redirected to wildfire suppression, don’t expect government employees or contractors to repair problems quickly. Typically, issues will persist until teams of volunteers fix them. The PCTA is still repairing trails and signs damaged by wildfires in 2018.

Long-term Landscape Changes

For years after a wildfire, you might hike through blackened scrub and forests, over burnt deadfall, with trails difficult to follow or gone, while skirting newly-sprouted noxious species like poodle-dog bush and thistles. Expect on and off closures of trails, trailheads, forests, and parks.

In some burned areas, you’ll encounter restoration activities: dead tree removal, trail repairs, campground rebuilding, tree planting, and controlled burns. And you might see drones in the sky, dropping seeds, herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers, or just surveying the area. Workers may move some trails, outhouses, campgrounds, and ranger stations, leading to map errors. Land managers may choose to close or abandon certain features forever.

It’s Just Not the Same Here Anymore

And sometimes nature takes other paths. Post-fire erosion can quickly strip hillsides, leading to poor plant growth. Fires can burn so hot it sterilizes the soil and kills seeds and roots, delaying repopulation by decades. So-called “invasive species” may live up to their name, filling ecological niches before native plants and animals have a chance – and forever changing the biological landscape. Plus, the local climate might have changed so much that certain trees can’t grow there anymore. These new landscapes also might be much more fire-prone than the old ones, adapted to warmer and drier conditions.

For many years burnt-over areas could have streams and lakes filled with ash and debris, undrinkable water, and experience more massive and more frequent landslides. Since fewer trees and bushes will suck water from the ground and cast shade on snowpacks, rivers and streams can carry earlier and much higher spring runoff, making for more challenging crossings. Higher lakes and reservoirs could temporarily drown trails and campsites. And research shows that some burned areas get significantly hotter, while others cool a few degrees.

Finally, resupply towns and resorts often sustain severe wildfire damage. Some could close forever. Many will suffer from polluted tap water and frequent power outages for years, making bottle refills and battery charging even harder.

Land Management Changes

This year, federal, state, and local land managers issued many emergency orders, including total closures and stove bans. And some of them might get more enthusiastic about using more prescribed or cultural fires or letting burn fires that don’t directly threaten civilization. But others will rely on old practices like logging disguised as thinning or forest management.

Here are some of the potential impacts on backpackers.

Stoves and Shovels

Expect significant, possibly permanent changes in stove and campfire policies for many western U.S. parks and forests. Authorities could prohibit everything but off-the-shelf stoves with a valve, as they have from time-to-time in the past. Stoves burning gasoline, kerosene, alcohol, wood, and hexamine might be banned due to their perceived fire-starting potential. For a short time, National Forests and BLM lands in California prohibited all “ignition devices,” including stoves, lighters, and fire steels – meaning no-cook meals only. Dreaming next to a campfire in the western backcountry seems doomed.

Yet banning stoves and campfires increases other risks. You’ll have nothing but body heat and possibly wet insulation to prevent hypothermia. You won’t be able to start rescue signal fires. And no more purifying water by boiling it.

Don’t be surprised if some land managers require backpackers to carry a shovel. They’ve forced whitewater rafters to carry those tools for decades, to put out “escaped campfires.” While camped next to a river on rocks and sand. During campfire bans.

Feller Bunchers and Herbicides

Many parks and forests might ramp up so-called mechanical thinning operations using powered equipment ranging from chainsaws to feller bunchers. You’ll definitely wake up when noisy machines in the same canyon roar to life. I love the smell of engine exhaust in the morning – that’s why I went backpacking!

And the U.S. Forest Service often applies herbicides like glyphosate (aka Roundup) and dicamba after wildfires to knock down unwanted plants and allow commercially-valuable trees to grow.

Cultural Fires and More Park Closures

If we’re lucky, government agencies will allow more areas to burn using prescribed fires or cultural fires overseen by Indigenous peoples, who learned to manage fire-adapted landscapes over many millennia. Before European colonization, Native Americans in California often burned over 18,000 mi² (47,000 km² ) every year. The Karuk Tribe in Northern California is just starting to work with the U.S. Forest Service to expand these culturally and environmentally vital fires.

Since 1970, Yosemite National Park has used prescribed burning and allowed selected backcountry fires to blaze without interference for weeks or months. Land managers might follow the example of Florida, which for the last 100 years has practiced widespread controlled burns. A fire big enough to make headlines in California is barely noticed in the Sunshine State. And ranchers in Kansas set fire to more than 3,000 mi² (8,000 km²) annually to improve grazing. Yet it took Sequoia National Park more than a decade to gain approval and the right conditions for a 1.6 mi² (4 km²) prescribed fire.

We might see an expansion of forest and park closures during all or part of a fire season. I wouldn’t be surprised if some areas close to recreation for many years due to high fire risk and lobbying from surrounding suburbs.

Emotional Impacts

Imagine hiking for days through blackened forests, with occasional unburned patches, or passing the remains of animals that perished in the fire. It’s okay to cry. It’s okay to be angry. It’s okay to feel whatever you feel.

And don’t be surprised if fear comes up. Fear that the fire could return, or fear that your favorite area that hasn’t burned yet could go through something like this. Those are all normal reactions.

Your favorite stream crossing or your favorite view may be unrecognizable. That post-trip ice cream bar that you always enjoyed at the mom and pop resort? Gone. The rustic buildings replaced by piles of ash and broken foundations. Beautiful forests, shrublands, and grasslands may change dramatically as new trees, bushes, and herbs move in.

But life on earth is always changing. We can learn to appreciate a new landscape with the right knowledge and attitude. Often by the time a burned-over area re-opens, the first signs of life are appearing. Healthy green sprouts carpet the hillsides. Birds return quickly to take advantage of new shoots and open skies and fill the air with song. You can rejoice in the renewal of life.

Be prepared for a wide range of emotions as you backpack through an area that’s been through a devastating wildfire.

Advocacy

Experiencing vast tracts of devastation and altered landscapes might motivate you to advocate for healthy wildlands and reduce future destruction. Fires are a critical part of the ecosystem and native culture in the Western U.S. and many parts of the world.

Maybe you can do something to prevent enormous landscape-changing wildfires. Let land managers know that you support prescribed fires, cultural blazes, and letting backcountry wildfires burn. If you live near wildlands proposed for these fires, don’t automatically oppose them. This year’s mild wildfire could prevent next year’s catastrophic blaze – which won’t even pause at your property line. And support non-profit groups that advocate for better forest management, far beyond raking and logging.

Adapting to Changes

How can backpackers adapt to a future with more and bigger wildfires, over an extended season, plus forests and parks with new rules?

Skills and Tools

It might be time to learn a new skill – backpacking without cooking. Except that going stoveless might mean eating differently and (gasp) carrying more weight.

In areas with bad water quality, consider using activated charcoal filters to remove more known and unknown nasty compounds. Simple membrane filters, chemicals, boiling, and UV won’t work. One California lake hasn’t returned to pre-burn pollution levels after more than 13 years.

Switching Times and Locations

Rethink trip timing, perhaps backpacking less during lengthening wildfire seasons and periodic closures, and more in the formerly colder and wetter months. In much of Southern California and other parts of the world where wildfires are nearly a year-round problem, that might mean going elsewhere.

Many people want to reduce their exposure to herbicides and pesticides. If you discover that land managers are using those chemicals to promote wildland “health” in an area – maybe you should consider a different hike.

And some trails will stay off-limits until they get rebuilt. Consider volunteering on trail crews to help pay back and pay forward enjoyment of the backcountry.

Supporting Each Other

Take a friend along for your first hike through a recently-burned area that you love. Share your feelings to help both of you deal. You can support each other as you work through intense emotions – and maybe deepen your friendship.

Be careful in helping someone else experiencing strong emotions. Reserve your judgments. Be supportive. Don’t tell them how they should feel or how they should react. Helping another person with their emotions can help you process your own. And you’ll both end up more content.

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed before, during, and after trips through scorched wild areas. Stay in the here and now. One foot in front of the other, one sip of water after another, one deep breath leading to the next. Enjoy each moment of nature’s renewal.

Setting Good Examples

There are few documented cases of backpackers starting wildfires. But that’s not the public perception. We should lead by example, going beyond the legal requirements, and doing much more to avoid setting blazes. I’m not recommending that everyone switch to uncooked food forever – that’s not even wise for trips in frigid weather. But the safer you can make your meal preparation, the better.

Respecting closures and new rules while practicing Leave No Trace, especially when people are watching or when you post to social media, can encourage other trekkers to make this new way of life part of everyday practice.

As backpackers, we have special responsibilities to leave natural settings “unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” That includes changing where, when, and how we pursue our passion, further minimizing our chances of starting wildfires, and modeling responsible behavior. These changes could include switching from the absolute lightest equipment to safer-for-the-wildlands gear. Think of it as owing the Earth some ounces (grams).

Conclusion

As I researched and wrote this story, new backcountry blazes started, and too many existing ones kept growing. Alarming scientific studies and shocking tales appeared daily. It honestly seems like we’ve entered a new wildfire era.

Backpackers must adapt to larger, faster, more frequent, and more catastrophic wildfires and their aftermaths. Some of these changes will be easy – others will be tough. And we should set good examples for other backcountry visitors as we trek into this brave new world.

Life is full of risks. Take reasonable precautions and learn to enjoy a changed and changing landscape when backpacking after a fire.

More Information

Creek Fire forces hikers into ‘Mordor’ smoke and across Sierra, including a boy and dog, Fresno Bee

https://www.fresnobee.com/news/california/fires/article245629010.html

Six astounding stories from backcountry visitors trapped by wildfire, including one first time backpacker forced into an off-trail, cross-Sierra death march – by headlamp. Many good decisions, some less good. Highly recommended.

2020 Western United States wildfire season, Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_Western_United_States_wildfire_season

An irregularly updated overview of this catastrophic, but historically wimpy fire season.

The West’s infernos are melting our sense of how fire works, WIRED

https://www.wired.com/story/west-coast-california-wildfire-infernos/

A chilling account of how wildfire behavior has dramatically changed for the worse, the scientists trying to understand why, and how we might adapt. Highly recommended.

Unsafe to drink: Wildfires threaten rural towns with tainted water, CalMatters

https://calmatters.org/environment/2020/10/california-wildfires-unsafe-drinking-water/

Reports on seriously polluted rural water systems after California’s wildfires this year.

The loss that’s killing the West’s wildlife, The Atlantic

How wildfire patterns changed from patchy destruction to widespread devastation, threatening endangered species, and entire landscapes.

California blooms again after last year’s fires—but it’s not all good, CalMatters

https://calmatters.org/environment/2019/02/californias-charred-hills-bloom-again-not-all-good/

Recent Malibu wildfires triggered changes in plant species that can be good, bad, or both. An example of what’s happening in many landscapes.

4 Million acres have burned in California. Why that’s the wrong number to focus on, National Public Radio (NPR)

A good argument for reinforcing and protecting human communities in the wildland-urban interface while letting the backcountry burn.

Concerns grow about herbicide use in wildfires’ wake, E&E News

https://www.eenews.net/stories/1063715827

The U.S. Forest Service often applies glyphosate and dicamba to manage forest recovery.

What the west can learn from Florida about forest fires, Outside

https://www.outsideonline.com/2320206/prescribed-wildfire-solution-florida

Megafires don’t even make the news in Florida, where they’ve learned to live with and manage fire-prone landscapes over the last 100 years.

‘Silver lining’ in wake of Point Reyes wildfire, San Francisco Chronicle

This year’s Woodward Fire in Point Reyes National Seashore is already showing promise of a net benefit to the landscape.

Burn area safety, Pacific Crest Trail Association

https://www.pcta.org/discover-the-trail/backcountry-basics/fire/burn-area-safety/

A good explanation of the risks that backpackers should manage when traveling through charred areas.

Related Content:

More by Rex Sanders

In the Forums

Skills and Gear

- Our three-part series on dealing with wildfires while backpacking is a good companion to this essay.

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Product mentions in this article are made by the author with no compensation in return. In addition, Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › Adapting to Changing Wildfires: Part Two