Stories Begin to Appear

I picked up my friend Clayton from his apartment near the University of Utah and we headed south from Salt Lake City on I-15 with snowflakes swirling around us. The pale sky made me cold as I imagined backpacking in the Bear’s Ears area in January. I reached for the heat and slid the dial a bit more to the right. Warm air blasted my face. Was I prepared for this?

It would be my first adventure in the Bear’s Ears area. Prior to this trip (which occurred in my early 20s) I had been more interested in the simple aesthetic beauty of desert canyons. Water pouring over orange sand, and fragments of the cobalt sky reflected in it. But after a while, I started to think more deeply about places. The beauty remained, but it began to penetrate time in both directions: centuries into the past, and centuries into the future. And if a particular place — say, Coyote Natural Bridge in Coyote Gulch, for example — was here 800 years ago, who walked under it? What did it mean to them? As these questions developed, the existence of the stories of the land began to appear. But not the stories themselves, just the fact that they exist. I could start to see them, like unlabeled books on a shelf I couldn’t quite reach. First I would have to start walking and asking questions, then maybe, just maybe, a few of those layers would start to reveal themselves.

First stop: Comb Ridge.

By the time we were bumping down Butler Wash hours later, I could suddenly smell beer. One of the beers behind the seat had sprung a leak from all the jostling back and forth.

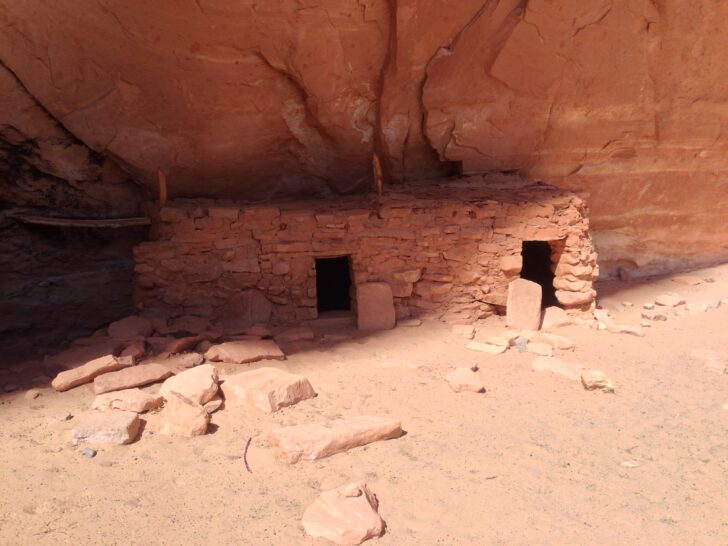

Just before the golden hour, we found a pullout in a cow-trampled sagebrush flat. There was an old, rusted-out trough being used as a fire ring. We decided we’d use it too. But first, we would walk up the nearest arroyo we could find towards Comb Ridge. I had heard that there were ruins in every single one of these little canyons, so choosing at random would be a good test. Before we even entered the short canyon we spotted a granary high up on the cliff. We both wondered aloud how they reached the spot, much less built a structure there.

“Don’t you think you could prop a log up there and then use that ledge to pull yourself up?” Clayton speculated.

“Maybe,” I said. “But then think about hauling those bricks up there.”

“True.” Said Clayton.

We kept looking for a minute but the puzzle did not come together, so we decided to let the structure remain a mystery and turned and walked up the canyon. Within a few hundred feet we found another structure, this one at ground-level, against a south-facing cliff. It was in sad shape. The roof had long since caved in and the walls were working their way to the earth. Old, dried fragments of cowshit peppered the dirt floor, and coarse, black hairs clung to the edges of walls where cows rubbed against them scratching gnat-bites and fly-bites. No wonder this old house was falling apart — its new tenants were the wrong size.

The clouds above us turned from gray to orange against the turquoise January sky and we began to amble back towards the car. That night was around zero degrees Fahrenheit (−18 °C) and my sleeping pad deflated: Russian thistle, I assumed. I cursed the cows (misdirected curses, I know) silently as I got dressed in the dark. I dug an old synthetic sleeping bag out of the car, walked back to the tent, and placed it over the deflated pad. I removed my shoes and reentered my bag shivering. I waited for cold spots. None. It worked.

The next morning we hiked to the top of Comb Ridge so we could get a better idea of where we were. There was the big, juniper-covered mound of Cedar Mesa to the west and the slightly taller Dark Canyon Plateau to the northwest, where the namesake buttes of Bear’s Ears sit. In the south, beyond the long spine of the ridge was the San Juan River. I couldn’t see it, but I knew it was there. We didn’t linger long though — we were on a mission.

The Fight For and Against Bear’s Ears

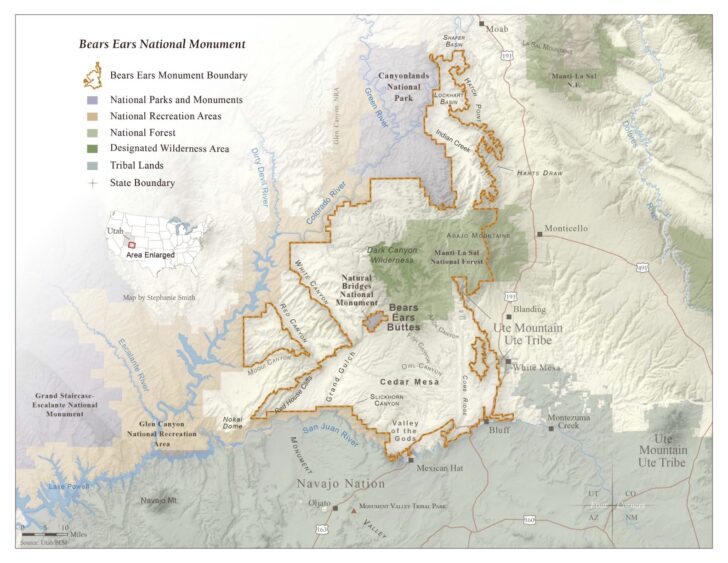

We sat at the top of Comb Ridge in January of 2011, so about five years before the area would come to be known as Bear’s Ears National Monument. Most of what we were gazing out on — and much we couldn’t see from that vantage — would be included in the designation. I didn’t know it, but around that time moves were already being made to increase protection in the area. Just a year later, in 2012, the nonprofit Utah Diné Bikéyah (UDB) was formed.

Utah Diné Bikéyah began to create a comprehensive ethnographic map of the area, plotting the layered histories of several cultures as a starting point from which to begin thinking about how to implement a new conservation strategy. By 2013 they had come up with a proposal for the Diné Bikéyah National Conservation Area, which was about 1.9 million acres (7,690 km2) in size. In response to these efforts, Utah Congressman Rob Bishop along with Representative Jason Chaffetz drafted the Public Lands Initiative (PLI). What appeared at first (as promoted by PLI representatives) like a conservation compromise actually documented policy proposals that would increase extractive activities1, reduce decision-making representation of tribes2, and ensure that future presidents would be unable to designate a National Monument in the seven counties participating in the PLI and where future monument designation would be most likely.3

In response to what has been called a bad-faith PLI, the Bear’s Ears Inter-tribal Coalition was formed in 2015. The group is made up of five tribes: Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, and Uintah Ouray Ute, each of whom has deep connections to the Bear’s Ears area. They encouraged President Obama to designate those 1.9 million acres identified by UDB. His administration considered both UDB’s 1.9 million acres and the smaller proposal laid out in the PLI’s map, eventually settling on 1.35 million acres for Bear’s Ears National Monument, which was somewhat of a compromise. Of course, not long after this, President Trump reduced the area by over 80%. Now a third administration is looking at the monument. President Biden signed an executive order on his first day in office, promising to have a look at the boundaries. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American in a President’s Cabinet, visited the area the second week in April 2021.

The Ruin

All the while, I have backpacked periodically in the area, seeking out well-known ruins, stumbling across surprises. Back in 2011, when Clayton and I were given rough directions to a site of particular interest, my coworker had drawn his finger in a circle around an area of the map, a vague, mile-wide radius. He said he didn’t want to give us precise directions because that would ruin the thrill of the hunt. A mile radius looked small on the map but would be a different story in reality.

The snow was six inches deep as we plodded into the canyon in the light of day. Though it was barely above freezing we were soon in t-shirts. At the bottom of the canyon, the snow was even deeper, almost a foot in places. We walked into the vague radius that housed the site and looked at the terraced canyon walls for some sign of residence. If I had to live there, where would I choose to live? Clayton continued up the canyon while I scrambled upwards to what had the appearance of being a good lookout. There I found a small ruin with three doors, a second small ruin, and the whole high shelf strewn with potsherds.

It wasn’t the site we were after, but something about it completely bowled me over. I picked up small, grey corrugated pieces with the fingerprints of their makers still pressed into them. The clouds above the canyon, flat and gray just a second prior, became orange catching the last light of day, and suddenly expanded like leavening bread towards the earth. The sudden closeness of the sky, the descending cold, the inevitable night, and my aloneness at the site sent me hurtling through time. Or rather everything that ever was and would be seemed to be happening all at once. I had been to Mesa Verde, the Pantheon, and Se Grada Familia, and those places had filled me with awe, but not like this.

I replaced the tiny pieces of broken wares and looked at the sky. Fading fast. I’d better get going. I scrambled down, being careful not to slip on the snow-covered slickrock. Clayton and I reconvened at the bottom. He told me he had stopped looking for the site altogether, instead following a deer track just to see where it went. The snow was deep and the night began to get colder. The sky went from winter-blue to purple and the leavened, orange clouds deflated and retreated back into the firmament far from earth. We never found the site but it didn’t matter.

How Does a Backpacker Give Back?

I, of course, didn’t take any potsherds, arrowheads, or corncobs. The only thing I took away was the experience of being there: awe, wonder, and feeling like I was seeing into deep time. But, according to archaeologist and conservation advocate R.E. Burrillo in his book Behind the Bears Ears: Exploring the Cultural and Natural Histories of a Sacred Landscape, I may still have been engaging in what could be considered a form of pillaging. Let me explain.

Burrillo tells the story of getting his truck stuck in a creek in the Bear’s Ears area around Christmas many years ago. He is saved by a climber who winches his truck out of the ice. The climber asks Burillo why he likes archaeology. “What I said at the time is that I love hiking and backpacking to archaeological sites, investigating and taking photos of them,” Burrillo says. “Becoming an archaeologist meant turning my favorite hobby into a job, as Confucius supposedly advised.” The climber thought about this and then asked him what he gives back.

Burrillo had no good answer at the time. The climber said, “I know a lot of people who don’t give a shit, they don’t think much deeper than buying new gear and putting up routes, but I know these places wouldn’t look very much like this if we didn’t do something to look after them.”

Many years later, Burrillo finally found out how to give back. He became one of the primary voices calling for the designation of Bear’s Ears National Monument. He wrote op-eds, researched, and worked on advocacy projects. And, of course, wrote a whole book about the area he loves so much.

His story urges me to ask what I have done to give back. So far I have given back close to nothing. The concept of reciprocity wasn’t in my vocabulary in 2011, and now, ten years later, I still don’t know exactly how to give back to a place that has provided me with experiences like the one described here. But this theme keeps finding me, prompting me to consider it more seriously. Recently, I had the privilege of interviewing writer and adventurer Craig Childs for a podcast episode, and he touched on the same concept. “I’ll be dead and gone before I ever really figure out what needs to be fed back into this place and the people of this place,” he says. “But at least I can get close, at least I can do my best.” In his case, each book he writes is an endeavor to give back to the desert he loves. He takes what he has observed while walking through remote canyons and over orange slickrock and transforms the observations into words that have the intention of drawing the reader into the experience so that they too can develop affection for these places. Through affection we can begin to learn what a place needs, how we can help, what role we can play.

It’s a small gift, but I hope that even this article — my meager effort to become more aware of the reciprocity asked of backpackers like myself — is an attempt to give back to the places that have given me so much.

Further Reading

- Behind the Bears Ears: Exploring the Cultural and Natural Histories by R.E. Burrillo

- The Madness of Dissasociation — an interview with Craig Childs

- Biden has to ‘get this right,’ Deb Haaland says of monument decision after Bears Ears tour

Endnotes

- PLI SEC. 1102. ACTIONS TO EXPEDITE ENERGY-RELATED PROJECTS. “(a) In General. — The State of Utah —(1) may establish a program covering the permitting processes, regulatory requirements, and any other provisions by which the State would exercise the rights of the State to develop and permit all forms of energy resources on available Federal land administered by the Price, Vernal, Moab, and Monticello Field Offices of the Bureau of Land Management…” The main takeaway from this section seems to be the fact that they were trying to move energy development decision-making from the Federal Government to the State.SEC. 1103. PERMITTING AND REGULATORY PROGRAMS basically makes permitting easier.

- PLI SEC. 110. BEARS EARS ADVISORY COMMITTEE. This section of the PLI states that tribes would have had a consultative rather than managerial role with regards to Bear’s Ears. Committee members would have been chosen by the Secretary of Interior. This would have allowed then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke to choose people who wouldn’t be noise-makers. In addition, these committee members would have had to live in Utah which leaves the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (located just across the border in Colorado, but still with a strong vested interest in Bear’s Ears), out of the decision-making process.

- The Antiquities Act provision is in section 3 of H.R.5781 which was a companion bill to the PLI. It reads: “A national monument designation, or a boundary adjustment that increases the size of an existing national monument, under section 320301 of title 54, United States Code, within or on any portion of Federal land in the counties of Summit, Uintah, Duchesne, Carbon, Grand, Emery, and San Juan, in the State of Utah, shall be made only pursuant to an Act of Congress.”

Related Content

- More by Ben Kilbourne

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage. Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead. Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › The Overlook: Giving Back to Bear’s Ears