Topic

Air permeability vs. moisture vapor transmission rate (MVTR): which one impacts moisture transport more in wind and rain jackets?

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Home › Forums › Campfire › Editor’s Roundtable › Air permeability vs. moisture vapor transmission rate (MVTR): which one impacts moisture transport more in wind and rain jackets?

- This topic has 92 replies, 19 voices, and was last updated 11 months, 2 weeks ago by

Philip F.

Philip F.

-

AuthorPosts

-

Jan 26, 2023 at 1:40 pm #3771481

Brett, if you’re talking to me, then I must have been unclear. :)

Agreed that Stephen is one of the heroes of this community. Also Richard Nisley and Roger Caffin; I think I have read most of what they have written here. I never gave a thought to fabric engineering before I started reading here a couple of months ago. Now I think way too much about it.

Please forgive me if I sounded critical. It’s not criticism; it’s just unemotional analysis. Perhaps my “inner Sheldon Cooper” may inadvertently pop out from time to time.

Agreed about all you said, but it’s basic stuff. I’m trying to ask questions that remain after all of the excellent discussion that has gone on for more than a decade at BPL.

If you were not talking to me, then never mind. :)

> “MVTR mainly comes into play with a rain or wind shell with a

> very low CFM when you have to button it up”Yes, that is my lifelong experience. Without benefit of real data, I think that both air permeability and moisture vapor transmission are involved in what I sense as “breathability”, with air permeability being the far larger contributor. This article appears to reach a different conclusion; hence my questions.

Jan 26, 2023 at 1:46 pm #3771482Just our own practice: a single layer of loose flappy Taslan under all dry conditions down to ~0 C. When we stop we do add.

Below 0 C we might have a light thermal layer under the Taslan for half an hour while we get going.

Very light rain and ‘not-cold’ conditions: that Taslan layer is all. Heat output evaporates the water.

Rain: silnylon poncho over body and pack, as often shown.No vests, no pit-zips, no fuss.

Cheers

Jan 26, 2023 at 2:11 pm #3771484Roger, Yep, that’s not off from me and my Ferrosi jacket (although I do wear a base layer underneath it). I don’t have a clue what Taslan is, other than both fabrics are some kind of nylon.

Love your mountain poncho. If I replace my front-zippered poncho someday, that’s the direction I would take (perhaps a Packa, as you have suggested in the past).

I watch Stephen’s investigations into tech membranes closely. I tried one of them; for me it is kind of “meh”. But there is hope that the industry will continue to improve. Perhaps the investigations here at BPL may help to influence them in the right direction.

Jan 26, 2023 at 2:56 pm #3771497I have been following this thread closely for a while now. As someone who has worked in the performance materials industry for over 20 years I am really interested to hear a lot of the comments. I also have many of these types of jackets and personally use them for my own adventures, cycling, backpacking, trail running, etc. I think the lightweight/wind shell category is one of the most complicated and misunderstood categories in all of outdoor apparel.

One key thing I have seen is that each brand has their own target for performance when they design a jacket, some brands focus on breathability, some on wind and water resistance, also weight, durability, packability, and not surprising – cost! Most are trying to find some balance of these variables so inevitably you always have some compromises in the final product.

I do find that cost is the one variable that is very key in how a brand approaches this product. As a reality most consumers don’t understand why they should spend $100-200 on a jacket that is not even waterproof. Very few people recognize the need for such a product or are unable to justify the cost of adding it to their quiver. Brands are keenly aware of this pressure on cost which can lead them to compromise on material performance in order to hit a price target. One issue that is not known to consumer is that there is a duty rate increase on materials that are not “rainwear”. There is a “rain” test (AATCC 35) that is applied to the garment or fabric that determines if it can be classified as rainwear. Rainwear has an import duty of 7 ish% and non rainwear is something like 23% so for a brand it is a critical cost decision. However to pass “rainwear” the fabric needs to be fairly shut down or coated which means less breathability (air permeability). Usually this means either a high-density material or some kind of coating to reduce water penetration and both reduce breathability. The other option is to just pay the higher duty to make a more breathable (air perm) product which will impact the retail price dramatically (and likely sales). Anyway just some insight, I like the conversations here but it is good to remember that these products don’t live in a bubble where there is some perfect solution, for most people it’s about finding what works and at a price you can justify.Jan 26, 2023 at 3:33 pm #3771499Wow, that’s great info, Kenny G. Thanks… I suspected that the industry lurks here. Too bad about the import duties. I’m pretty sure that there is an audience interested in technical wind garments. They are, however, under-served and mostly under-educated (except for the BPL portion of the audience).

> the lightweight/wind shell category is one of the most complicated and misunderstood…

Part of that is the industry’s fault because they don’t bother to even attempt to explain it. Nothing personal. ;)

It took me a while to wrap my head around wind shell tech. There are a few monster threads on BPL that discuss wind shells in depth, often started by @richard295. I haven’t seen him post recently, but he is another of the heroes of this community. He was/is a proponent of the military specs for Level 4 and Level 5 of the PCU/ECWCS system developed at Natick Labs. They reportedly settled on CFM around 35 for L4 and around 5 for L5, both with >300 mm HH. Those kinds of specs are mostly unknown among civilians outside of BPL.

I don’t even know if those specs are “right”. It’s just that they are published. I ordered a PCU L4 from eBay in an attempt to find out.

Customers could understand this if it were explained clearly. It isn’t any more complicated than, say, torque vs horsepower.

Is cost the reason that EPIC is not more widely used for commercial wind garments? It would appear to solve many problems of DWR.

Jan 26, 2023 at 3:45 pm #3771500Epic and other silicone-based finishes are available from various sources, however silicon can significantly reduce breathability. There is however an uptick in interest in silicone now that most DWR’s are shifting to PFC free and have very limited durability. I think it is likely there will be more products using silicone finishing in future. As for consumer education it is not as simple as it sounds, people have to want to know something. As you can tell by reading this thread it is not as simple of a product to explain to someone as say Waterproof/Breathable… BPL is a very small community with a very specific focus. Kind of why I like to hang around and read threads…

Jan 26, 2023 at 3:54 pm #3771502I must emphasise that I have no current info on cost for EPIC.

Just how windproof an EPIC fabric will be depends almost entirely on the base fabric. The silicone coating on the fibres has little to do with that.What EPIC does offer (imho) is neither windblocking not rainproofing, but what we could call ‘non-wetting’. As such it is quite good for ski jackets: it sheds the snow without getting wet.

Cheers

Jan 26, 2023 at 4:15 pm #3771503> What EPIC does offer [is] … what we could call ‘non-wetting’.

Roger: I see. So the “>300 mm HH” spec is accomplished by the tightness of the weave, not by the EPIC encapsulation?

Kenny G: It is encouraging that the industry is at least interested in silicone finishes. The fabrics may be available, but the garments are hard to find other than military surplus.

> As for consumer education it is not as simple as it sounds. People have to want to know

Now that you say it, it occurs to me that the public learned about torque from car magazines; not from the manufacturers. Perhaps it is incumbent on BPL to continue to educate customers to ask the right questions?

Jan 26, 2023 at 4:18 pm #3771504Hi Bill:

GoreTex outperforming a Houdini Air on breathability?

There is nothing in my article that would support such a claim. In several articles, I have provided performance data on various Gore products and, with the exception of Gore Shakedry, the Houdini Air will always have higher MVTR.

I wouldn’t normally wear a windshirt for running; more likely fleece or a sweatshirt. I interpret that as “CFM rules”. Maybe I’m wrong about the interpretation, but the experience stands.

I wear a WPB for running over a base layer when I need protection from wind or rain. It has to be pretty cold before I want much insulation during a run. A typical Polartec 100 wt fleece has air permeability of around 220 CFM/ft2. A typical wind shirt might be 5-20 CFM/ft2. A WPB will be less than 5 CFM/ft2 and typically closer to zero. The fleece will have a substantially higher R-value than a wind shirt or WPB. Sort of apples and oranges, but sure, at some point, high air permeability, assuming some elevated wind speed, will remove more vapor than a wind shirt or WPB. If you are running at 5 mph in still air, there is little air pressure on the outer garment, so you need very high CFM to provide comfort. This kind of comparison has nothing to do with the garments included in my test.

Consider this from one of my articles: When you are hiking in still air at 3 mph, the air pressure on your outer garment is about .0001 psi. Alternatively, the vapor pressure difference between your skin and ambient at a range of environmental conditions can range from 0 psi to .78 psi. The only time the vapor pressure difference approaches 0 is at very high ambient temperature and humidity. At all other conditions, there is more force to remove vapor by means of vapor drive than air circulation.

A confounding factor is the zipper: In real life we lower the zipper and pull up the sleeves when noticeably sweating. However, doing that would interfere with testing the effect of air permeability.

I think this means you are overdressed or the garment in question has insufficient vapor transfer capacity.

You may be missing the point of the article: over the range of performance of the garments evaluated, high MVTR can support more vapor transfer than high air permeability.

If I had done the test with an AirShed, with its very high air permeability and likely high MVTR (I have not measured one) this conclusion might have changed. You can have a garment called a wind shirt with sufficiently high air permeability that you will not be protected from the wind. I did not include garments like that in the test.

We know that certain wind shirts can have similar or even better MVTR performance than the best-performing WPBs. Usually, this comes with elevated air permeability. Under some circumstances, high air permeability may be desirable. Generally, not for me. Elevated air permeability (certainly over 20 cfm/ft2) will leave me cold when exposed to high winds and/or cold air temperatures. I prefer wind shirts with air permeability below 5 Cfm/ft2.

Nor have I ever claimed that a high MVTR is a panacea that will solve all moisture accumulation problems in a clothing ensemble. You still must layer in such a way as to balance excess heat production during your activity with the ambient conditions. A high MVTR WPB with adequate ventilation can provide a wider comfort range than many wind shirts. But any garment can fail to control moisture transfer due to specific weather conditions or high MET levels. You always have to layer responsibly.

I really don’t think you can make a blanket statement that the results of my research don’t reflect reality. It is possible that my test results don’t reflect your reality. The conditions under which my test was conducted are well documented. We know the various weather conditions, the terrain, the level of effort, the base layer, and the shell layers that were used. We know the air permeability and MVTR for the garments I tested. We know that the test was conducted at a significant and consistent MET level.

In your case, we don’t know anything about how you might have tested to reach your conclusion. We don’t know what WPB garments were worn, we don’t know their air permeability or MVTR. Critically, we don’t know your level of effort while wearing the WPB or the wind shirt. We cannot compare any 0f the critical variables present for any of your experiences, and we don’t know if they remain constant as you move from garment to garment.

One of the nice things about my test methodology is that anyone can do this test. All you need is a good scale to measure base layer weight before and after your activity and a heart rate monitor to keep track of your level of effort. You should be able to get adequate weather data for the test. You want a medium to heavy-weight base layer. A heavier wicking base layer will take longer to saturate and hold more moisture than a light base layer. So, let’s establish your reality by you repeating the test with whatever wind shirts or WPB shells you like but keeping track of the relevant data and results.

We will have to estimate your metabolic rate. (I had a metabolic test done so I could relate heart rate data to metabolic rate prior to conducting my test.) If you do the test with garments I have not measured, I can conduct MVTR and air permeability tests. I suggest that this is what it takes to substantiate your performance claims.

Now, there are wind shirts can provide better MVTR performance than a WPB. Only WPB fabrics with the highest MVTR performance can perform better than a typical wind shirt. Most WPB garments will have MVTR that underperform compared to typical wind shirts. So, when you do this test, I suggest using a WPB made from one of the fabrics listed in Bret’s post. I would not include any Gore fabrics (except Shakedry). Of course, a few wind shirts will outperform (for MVTR) many top-performing WPB fabrics. Some examples: OR Helium Wind Hoody (2021), BD Alpine Start (I have tested various years, all with similar results), Pat Houdini Air, Mountain Hardware Kor Preshell (2019), and some others. For me, the good MVTR performance of the Houdini Air, Alpine Start, and Kor Preshell do not translate into comfort because they have high air permeability. This means I will be cold in cold or cool temperatures with elevated wind because of high air permeability.

Let’s repeat some key points:

This article demonstrates that for the range of MVTR and Air Permeability tested, MVTR can remove more water vapor than air permeability.

Garments with high enough air permeability can remove more water vapor at the price of protection from wind and cold. Such garments were not included in the study. This study found that a garment with air permeability of zero but high MVTR removed far more moisture vapor than a garment with moderate MVTR and moderate air permeability.

It is certainly possible that a wind shirt might have high enough MVTR and low enough air permeability to provide protection from wind and cold. The OR Helium Wind Hoody (2021) is a good example. However, with a hydrostatic head of 405, it will not keep you dry in a steady rain.

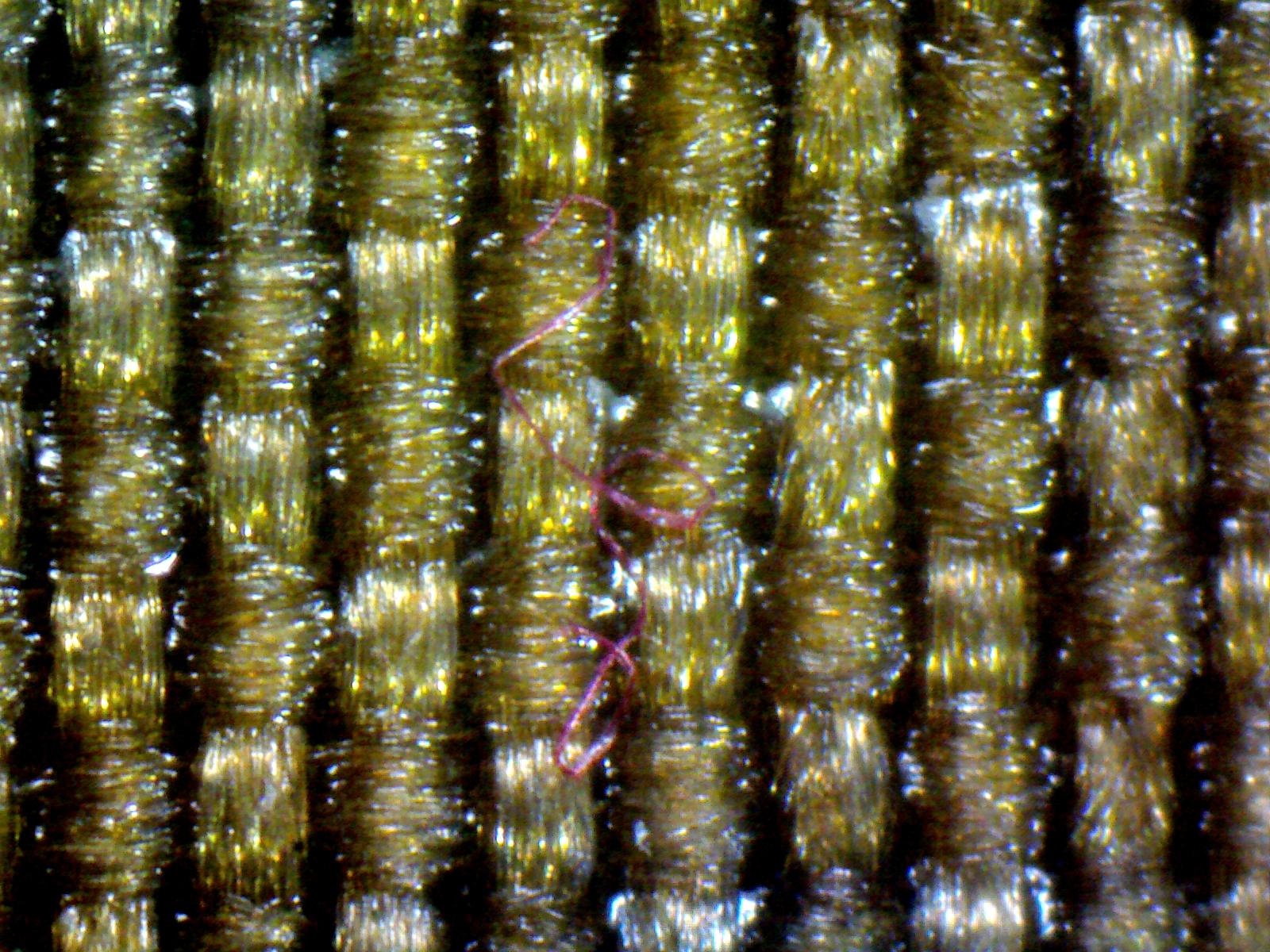

Jan 26, 2023 at 4:38 pm #3771505I have tested several Epic garments. Generally, they offer very low air permeability and mediocre MVTR. Hydrostatic head ranges from around 200 to a little over 1000. The coating provided permanent water resistance. When viewed under the microscope, there could be very poor control of the application thickness. The uneven coating application may impact hydrostatic head, air permeability and MVTR.

Nextec Epic Praetorian. Very tight weave produces both low air permeability and poor MVTR. You can see globs of silicone on the fibers.

Jan 26, 2023 at 4:50 pm #3771506Stephen, you are correct about Epic and other silicon “coated” fabrics. The silicon will clog up the fabric and reduce breathability. However with current state of DWR’s and the rush to PFC free chemistry there will soon come a point where consumers will have to decide if they want breathability at the risk of a jacket that just absorbs water. I think layering systems are more and more necessary as a way to manage and adapt to variable conditions. The problem with current DWR’s is at a point where you almost need a $10 poncho to cover up your $400 jacket to keep it from getting wet… But maybe there is another chat room for that conversation…

Jan 26, 2023 at 4:55 pm #3771507Woah, Stephen, there’s a lot of misquoting and context-shifting there. We are discussing your article; not mine.

My comments are about this:

> This article demonstrates that for the range of MVTR and Air Permeability tested,

> MVTR can remove more water vapor than air permeability.I am just pointing out that that conclusion doesn’t match real-world observations of many people (not just me). Perhaps your ongoing research will shed further light on the subject.

You’re a huge contributor to the public knowledge base. Thank you for your relentless search for the truth. (and, yes, I have read all of your papers on BPL.)

Jan 26, 2023 at 4:56 pm #3771508Some comments about ‘breathability’:

Our Taslan windshirts seem to breathe very well. Part of that may be due to the fabric itself: it is not coated and not ultra-light, although it does have visible pores between the fibres in the weave. Well, so much for the fabric.

What has not been mentioned yet is that the design of the windshirt means it is loose and flappy, even on the arms. My best guess is that more than 3/4 of the air flow out of the windshirt as it is worn is not through the fabric but due to bulk air movement as we move around. Now try to model that!Fwiiw, I still think that anyone complaining about a lack of breathability is simply wearing too much clothing. If you re ‘working’ (ie walking), your basic metabolic rate is probably enough to keep you warm down to near 0 C. You just don’t need multiple layers.

This is BackpackingLIGHT. Ditch the excess!

Cheers

Jan 26, 2023 at 5:01 pm #3771509Well said.

Can you describe what Taslan is? Pretend I live on the other side of the planet and have never heard of it before you mentioned it.

Jan 26, 2023 at 5:33 pm #3771513The definition of Taslan has evolved over the years.

At the start it was simply a plain weave fabric using air-textured fibres. Such fibres are not smooth straight fibres which you might find in a (usually shiny) UL fabric; instead the individual fibres in the threads are a bit curly or kinky – more like organic fibres. This is done by air-blasts near the spinnaret. The effect is to make the fabric more ‘textured’ and softer, unlike the smooth shiny UL fabrics.

Unlike a (cheap) polyester shirt which tends to cling to the skin if you are at all sweaty, a Taslan fabric will not cling. The surface of the fabric is too ‘fluffy’ for that.

Today you can find both nylon and polyester ‘Taslan’ fabrics. It comes with both a plain weave and a taffeta weave: the difference there lies in the sort of weaving loom used. You can even get a stretch version of Taslan: add a bit of elastane or supplex to the weave. In addition, the mfrs have started to experiment with coatings to enhance the properties: improved water rejection. I think the coatings may be silicone. I question their value.

I have some (a sample) EPIC-treated cotton fabric on my shelf. It was a disaster. The coating was much softer than the thread, and going though any scrub quickly ripped the coating on the surface off, so the fabric got very wet but could not dry very easily. I discussed this with a company techie who eventually fully agreed with my assessment (once he found out about my fabric knowledge).

It is not a really cheap fabric, but it is usually quite a strong fabric. It needs a strong poly-cotton thread rather than a cheap straight cotton thread, which is usually weaker. Our Taslan trousers and windshirts have lasted a long time in the harsh Australian scrub.

Cheers

Jan 26, 2023 at 6:01 pm #3771516Thank you. I know that you’ve been talking about it for years. Sounds great. :)

I accept your conclusion that it is strong and breathable and good. I’ve never seen (or noticed anyway) a garment described as being made from Taslan. Like your mountain poncho, you’ve got

uniquemost excellent custom gear.Jan 26, 2023 at 9:04 pm #3771533My Taslan is a few years old. It is nylon. As I said: my Taslan clothing lasts a long time.

To be honest, my Taslan gear is derived from clothing made by Macpac of New Zealand. But I don’t think they make these any more. The company has been through a few changes in ownership you see.

Most outdoors gear mfrs make most of their money from the street fashion market – psuedo-outdoors gear. And they get it made in China. Us walkers are very much a small bit off to the side. To be sure, there are a few cottage companies who focus on us – but they are few.

Cheers

Jan 27, 2023 at 1:44 am #3771544I have found the fashion/pseudo-outdoor-gear thing frustrating: Great features with inappropriate fabrics. Promising fabrics with inappropriate features. Shells without suitable pockets; cut too short instead of parka-length.

I can see the appeal of making your own, especially when you are a one-man R&D department.

Has BPL considered publishing a series of sewing tutorials?

Jan 27, 2023 at 12:51 pm #3771573MYOG – yes indeed. I am a fan.

There are hordes of sewing tutorials on the web, really hordes. The consensus seems to be that the best ‘solution’ is just to start sewing. It’s a craft really, and that you can’t learn it by reading. I agree.

MYOG to suit YOUR needs. That said, BPL does feature a fair bit of fabric info.

Cheers

Jan 27, 2023 at 1:00 pm #3771574Yes, there is a ton of info in the MYOG section. Just not “how to begin”.

I’ve looked elsewhere, although not rigorously. All I found that looked suitable was TheJasonOfAllTrades YouTube channel. Perhaps that’s enough. Thanks.

Jan 27, 2023 at 1:17 pm #3771583There is a huge number of quilters out there, and they have lots of web tutorials. I infinitely prefer the text-and-photos ones rather than YouTube: you can’t ‘study’ a YouTube video. And a lot of amateur YouTube stuff is a waste of electrons anyhow.

But remember that the quilters and most others are sewing cotton fabric, not synthetic, and that their cotton fabrics are usually heavier than our preferred UL synthetics. This affects what needles, threads, stitch lengths and stitch tension we use. You can be a bit rougher with medium-weight cotton fabrics.

Some hints worth noting:

Sewing UL fabrics under tension, as shown here, gives much better results. Hold at front and back and stretch.

Use a light poly-cotton thread, not a heavy one, with UL fabrics. Plain cotton thread suited to cotton fabrics is easy to buy, but it is too thick for UL gear. Straight synthetic thread is strong, but can be tricky to handle.

Getting the right thread tension and stitch length for the fabric needs some experiment. Spend the time getting that right.

Synthetic fabrics slide around very easily: use LOTS of pins in the hems to keep it properly lined up and not skewed. Obviously you don’t put the pins in the rain-shedding areas; just the hems.

Cheers

Jan 27, 2023 at 6:27 pm #3771611I agree about YouTube in general. TheJasonOfAllThings seemed interesting because he is an ex-industry pro who does MYOG tutorials about outdoor gear. I use “Enhancer for YouTube” extension to give me fine control over playback speed (down to 0.1x), which makes it easier to study a vid. I also agree that reading is faster, and studying a good diagram can be the best.

Thanks for the tips. I’m sure they will come in handy.

Jan 27, 2023 at 6:37 pm #3771613Good diagrams, with written verifiable references!

Beats the heck out of a bloke waving his hands in front of a wobbly camera.And I still say that good design beats both air perm and MVTR.

Cheers

Jan 27, 2023 at 7:05 pm #3771614Yep. Now I just need to find a good source.

I believe you about design. Frogg Toggs is another example of the benefit of blousy design. Still, some fabrics are noticeably more comfortable than others. In lieu of more data, my sense is that air permeability matters.

Jan 28, 2023 at 11:29 am #3771651the point of the article: over the range of performance of the garments evaluated, high MVTR can support more vapor transfer than high air permeability.

I get the point of the article and recognize its potential value for a use case scenario where the user privileges totally blocking the wind above all else. That’s not my use case but HYOH.

What’s being called “high air permeability” here is relative to the parameters of the testing protocol, which deliberately exclude what most of us would call high air permeability today — fabrics between 40 to 80 CFM (and mostly above 60).

Hence, the reference to “high air permeability” above is misleading. Shouldn’t the sentence be amended to something more like this: “high MVTR can support more vapor transfer than incremental increases in air permeability within the low CFM limits specified by this test”?

Low CFM/high MVTR cannot compare to truly high CFM for moisture evacuation. When I’m working hard, I definitely want and prefer something like the Patagonia Airshed (CFM 60+) over any of the alternatives covered here. Just wish I could get similar in a lighter package.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Our Community Posts are Moderated

Backpacking Light community posts are moderated and here to foster helpful and positive discussions about lightweight backpacking. Please be mindful of our values and boundaries and review our Community Guidelines prior to posting.

Get the Newsletter

Gear Research & Discovery Tools

- Browse our curated Gear Shop

- See the latest Gear Deals and Sales

- Our Recommendations

- Search for Gear on Sale with the Gear Finder

- Used Gear Swap

- Member Gear Reviews and BPL Gear Review Articles

- Browse by Gear Type or Brand.