Late last year, United States President Donald Trump took action to reduce the size of two national monuments in Utah, Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante. His decision marked the first time in more than 50 years that land protection rollbacks have occurred at this scale. The decision has sparked intense debate over the President’s right to take such action and, more importantly, what kind of precedent this action could set for the future.

On one side, GOP (Grand Old Party, otherwise known as the Republican Party) politicians and many rural Utah residents that regard these protections as a federal overreach are delighted for the opportunity to establish their own regulations to protect and maintain these lands.

Shortly after Trump’s decision, Utah Republican Representative John Curtis sponsored a bill to officially recognize the two smaller monuments and prohibit new mining and drilling operations on the original 1.3 million acres. It would also create a new pair of management councils for each monument, which would be comprised of state, local, and tribal representatives.

But on the other side, local tribes and environmentalist groups are worried about the immediate threat to those lands and the dangerous precedent this might set. Shaun Capoose, a member of the Ute Indian Tribe Business Committee and the Bears Ears Coalition points out that the bill sponsored by Rep. Curtis gives President Trump the authority to hand pick members to sit on the aforementioned councils, including those from tribal areas.

Capoose says the bill would essentially be “a return to the 1800s when the United States would divide tribes and pursue its own objectives by cherry-picking tribal members it wanted to negotiate with.” He argues that tribal governments should retain the right to select their council representatives, not the U.S. federal government.

To more fully understand the potential impact of this decision, let’s start by taking a look at what exactly was included in the proclamation signed at the Utah State Capitol on December 4th, 2017.

What The Proclamation Means and Where it Came From

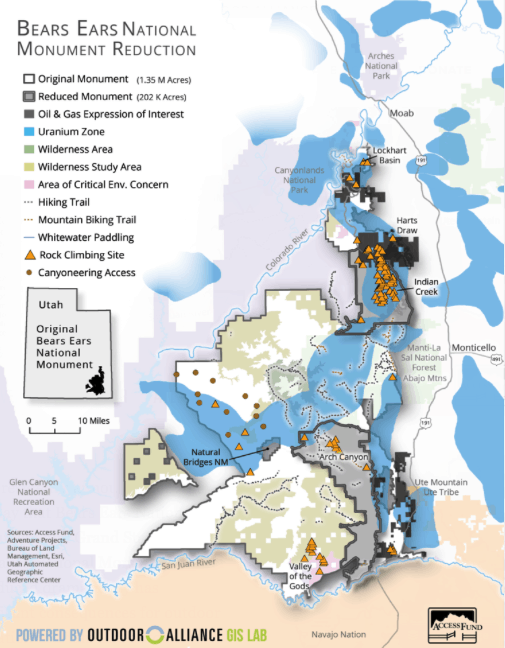

The terms of the proclamation championed by the President and Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke state that Bears Ears National Monument will be reduced by about 85 percent and will now include about 315 square miles of land.

Likewise, Grand Staircase-Escalante will be reduced by about 48 percent, a reduction from nearly 3,000 square miles down to 1,569 square miles. These maps tell the visual tale of the size and significance of the rollbacks.

At the start of the year, President Trump ordered Zinke to review a list of 27 national monuments. Under the terms of the 1906 Antiquities Act, the President has broad power to declare federal lands as monuments. Some of the controversy, however, lies in whether the specifics of the act also grant the President the authority to remove protections from federal lands without Congressional approval.

In addition to Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, Zinke also recommended reductions for Nevada’s Gold Butte National Monument and Oregon’s Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Decisions on these reductions have yet to be made. Also, Andrew Marshall’s recent story here, Wandering in a Thirsty Country, provides more information on recent developments at Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument.

Presidents have actually taken action to redefine the boundaries of national monuments on a number of occasions, the latest of which came in 1963 when President John F. Kennedy changed the boundaries of Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico, effectively reducing the amount of land under federal protection by just under 1,000 acres.

Trump’s decision, however, is far and away the largest land protection rollback attempted under the auspice of the Antiquities Act. Under Zinke’s advisement, President Trump has removed approximately 1 million acres from Bears Ears and another 300,000 acres from Grand Staircase-Escalante.

History of the ‘National Monument’ Designation

As mentioned earlier, the Antiquities Act of 1906 was a major step to give the President the power to designate historic buildings and archaeological sites as “national monuments.” Theodore Roosevelt declared Devil’s Tower in Wyoming America’s first national monument in September 1906 and subsequently designated 17 other national monuments during his administration.

According to the original proclamation that established Devil’s Tower, Roosevelt cited that the tower was “such an extraordinary example of the effect of erosion in the higher mountains as to be a natural wonder and an object of historic and great scientific interest and it appears that the public good would be promoted by reserving this tower as a National Monument.”

According to an article from the Harvard University Press on the origins of the Antiquities Act, one of the original motivating factors behind the passing of the Antiquities Act was the fact that many Native American cultural sites were being looted and in danger of disappearing entirely. A large group of scientists lobbied for the act because they believed these sites could not wait to be protected by slow-moving congressional action.

Since Roosevelt’s time in office, every president aside from three, Nixon, Reagan, and George H.W. Bush, has used their authority to establish national monuments. In total, more than 120 national monuments have been dedicated since 1906.

According to the National Park Service Archaeology program, however, several of these monuments were later abolished or redesignated by Congress. For example, the 85th Congress redesignated Petrified Forest National Monument a National Park in 1958 and Cinder Cone National Monument (created by President Teddy Roosevelt) was later incorporated into Lassen Volcanic National Park by the 64th Congress in 1916.

A Brief History of Land Preservation and Management

The mission of the National Park Service is to “[preserve] unimpaired, the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.”

Going back to the 1800s there were many elegant voices, including John Muir and Henry David Thoreau, who proclaimed the importance of protecting and preserving lands for the enjoyment and betterment of future generations.

Some on the government side, like forester Gifford Pinchot, believed that parks were best managed by a Forest Service promoting “the greatest good for the greatest number” through the well-managed regulation of timber and other resources.

Pinchot’s philosophy led to the damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley to provide a safe, stable water supply for the growing population in San Francisco, a move that more staunch conservationists like John Muir and Henry David Thoreau were ardently opposed to.

While these two sides adamantly debated the benefits of strict conservation versus responsible use and management, their debate signaled a vast improvement over the incredibly resource-intensive practices of the 1800s.

As a result, areas like Lake Tahoe benefited. Now known for forests as far as the eye can see and a lake with crystal clear water as blue as the sky, anywhere between 70 and 90 percent of the region’s forests were clear-cut during logging and mining operations throughout the late 1800s.

The establishment of Tahoe National Forest in 1905 helped to preserve some Native American travel routes, villages, and summer gathering sites but also served to slow logging and mining operations and set the stage for the region’s shift from a mining and logging hub to a year-round tourism destination.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In the years since the Park Service’s creation in 1916, countless individuals from all over the world have made use of America’s system of national parks, monuments, and landmarks. The value of untouched land, however, is hard to quantify.

Attempts to quantify the value of untouched land require the consideration of quality versus quantity, but it’s also a question of economic viability in contrast to the proverbial question of what’s best for the people.

Preserving a small section of canyon that was once home to the Anasazi Native Americans, for example, could provide insights into the history of the climate in that area and the downfall of a once-prominent people. The information that can be learned in this canyon can arguably provide more benefit than the economic gains that could be found by commencing mining or drilling operations in the region.

So, just what are we gaining by blocking development and restricting certain activities on these lands?

For many, there are countless intangible benefits to preserving a portion of our country untouched. For starters, the history, artifacts, and natural wonders that are preserved in America’s national park system are expansive, and potentially unmatched by any other country in the world.

But much deeper than that, untouched land, or ‘wilderness,’ gives us a place to disconnect from the concrete jungles where so many of us spend 99% of our lives. It was John Muir who said: “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity.”

Trips away from the regular, man-made landscape we frequent provide space to reflect, time to disconnect from technology, and opportunities to connect with Nature; a connection that can – and must – be rekindled.

But for some, the financial gains and job growth that come with increased mining, drilling, and other ventures outweigh the intangible benefits of untouched wilderness, and they too have a point. These economic gains can be reinvested in education, healthcare, social programs, and much more. These are all important to improving the overall quality of life here in the United States, and thus, we encounter the tricky balance that lawmakers and politicians are asked to strike.

Many of us depend on open, wild spaces to maintain our quality of life, but increasing access to affordable healthcare and the improvement of our education system are also noble initiatives that would seem to be amenable to many Americans.

Others believe that, in preserving “the natural and cultural resources” of this country, we have simply halted the harvesting of these resources for times of greater need. But has that need now arrived? And what do we lose from a cultural and historical standpoint by opening previously federally designated preservation sites to the development and the potential harvesting of natural resources?

It is true that part of the platform that President Trump ran on centered on the idea that the federal government needed to spend more time solving domestic problems and devote more money to improve the quality of life for “everyday Americans.”

In my graduate studies, we discussed sustainability as it related to tourism. One of the core ideas we looked at was the struggle to give equal consideration to economic, environmental, and social-cultural ramifications of tourism decision-making.

When approached from the perspective of sustainability, it made sense to utilize and cultivate resources that are more “local.” This means reducing foreign resource extraction and the importing of goods and materials and investing in domestic resources while also making a plan for the renewability of these resources.

Survivalists advocate the preservation of America’s natural resources and reliance on extracting resources, goods, and materials from the rest of the world for as long as possible.

I am still personally struggling with the challenges to both perspectives, but I often come back to the same basic question: is it better to become the greatest nation in the world by succeeding in making every other nation worse, or is it better to cultivate an internally sustainable system that many other countries in the world could model for their own benefit?

For my part, the latter certainly sounds like a more ethical approach that has the best chance to improve quality of life for the entire global community.

A Final Question to Consider

Perhaps the biggest question that the president’s decision to downsize these two monuments brings up is whether the federal government is the best entity to preserve these lands or whether state and local governments should play a larger role.

In the speech he gave to announce the rollbacks of the monuments, President Trump spoke directly to Utah residents (but also possibly to the entirety of the American people) when he said, “Your timeless bond with the outdoors should not be replaced with the whims of regulators thousands and thousands of miles away. I’ve come to Utah to take a very historic action to reverse federal outreach and restore the rights of this land to your citizens.”

The President’s statement was well received by some and viewed as mere lip service to others. Supporters, such as Utah’s Republican Senators Orrin Hatch and Mike Lee, appreciate the opportunity to decide how land in their region should best be used. But interestingly, President Trump’s statement contradicts the philosophy of the first proponents of the federal land management, such as Gifford Pinchot, who believed that a responsible federal regulatory body would be best suited to manage significant national resources to ensure “the greatest good for the greatest number.”

Opponents, some of whom have already filed lawsuits blasting the proclamation as illegal, lament what they believe to be an abuse of presidential power due to the lack of clarity over whether this action is protected under the Antiquities Act, and an affront to one of the nation’s largest collections of dinosaur fossils (in the case of Grand-Staircase Escalante) and sacred tribal lands (in the case of Bears Ears).

An overwhelming majority (98%) of public comments since the decision show support for keeping the monuments as they were and even Secretary Zinke acknowledged that “comments received were overwhelmingly in favor of maintaining existing monuments.” But Zinke later went on to dismiss those comments as “a well-orchestrated national campaign organized by multiple organizations.”

Interestingly, however, some polls conducted in Utah and throughout the Western states have turned up a variety of results both for and against the rollback. A January poll conducted by the Colorado College, for example, found the state almost evenly split on the subject, with 49% of Utahns opposed the reduction while 46% supported it.

Closing Thoughts

The question of who is best equipped to manage these lands is very difficult and complex. There are many interests that must be heard, and history suggests that coming to a solution that is amenable to all parties is nearly impossible.

Perhaps those with the deepest pockets and strategic connections have more influential voices than others. We’ve seen the need for further development and the potential for economic gain win out over desires for conservation and preservation time and time again, i.e., Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell.

But there will always be power in a well-organized and driven public opposition. As we move forward, it’s important that the federal government remains engaged with every group that has an interest in these areas and, indeed, in any national park or national monument that comes into question in the coming years.

The value of land and, more specifically, its value to future generations, cannot be estimated. It comes down to a question of ethics, and I for one would like my children to grow up with the ability to travel far and wide across this country, the ability to escape cities and developments and find open, untouched natural spaces, and pride in the fact that the United States has, and will maintain, the world’s greatest system of National Parks.

Sources

- https://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2017-12-04/trump-to-scale-back-2-national-monuments-in-trip-to-utah

- https://www.history.com/news/how-we-got-national-monuments

- https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/index.htm

- https://www.outdooralliance.org/blog/2017/12/7/what-the-national-monument-rollbacks-mean-for-outdoor-recreation

- https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/utah-national-monument-bill-john-curtis_us_5a54d031e4b0efe47ebcfc58

- http://www.legisworks.org/congress/59/session-1/publaw-209.pdf

- http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=24101

- https://www.deseretnews.com/article/900000045/times-in-history-when-us-presidents-have-acted-to-shrink-monuments.html

- http://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record/ImageViewer?libID=o293443&imageNo=1

- http://harvardpress.typepad.com/hup_publicity/2017/05/the-origins-of-the-american-antiquities-act-samuel-redman.html

- https://www.fs.usda.gov/main/tahoe/learning/history-culture

- https://www.nps.gov/archeology/sites/antiquities/monumentslist.htm

- https://www.regulations.gov/docketBrowser?rpp=25&so=DESC&sb=commentDueDate&po=0&D=DOI-2017-0002

- https://www.thespectrum.com/story/opinion/2018/03/02/do-utahns-support-bears-ears-national-monument-and-how-much/383638002/

- https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/zinke-doesn-t-care-what-you-think

Home › Forums › National Monument Reduction: What Are We Really Losing?