Factors that influence the ability to carry weight in a backpack:

- Conditioning

- Distance

- Elevation Gain

- Environment and Terrain

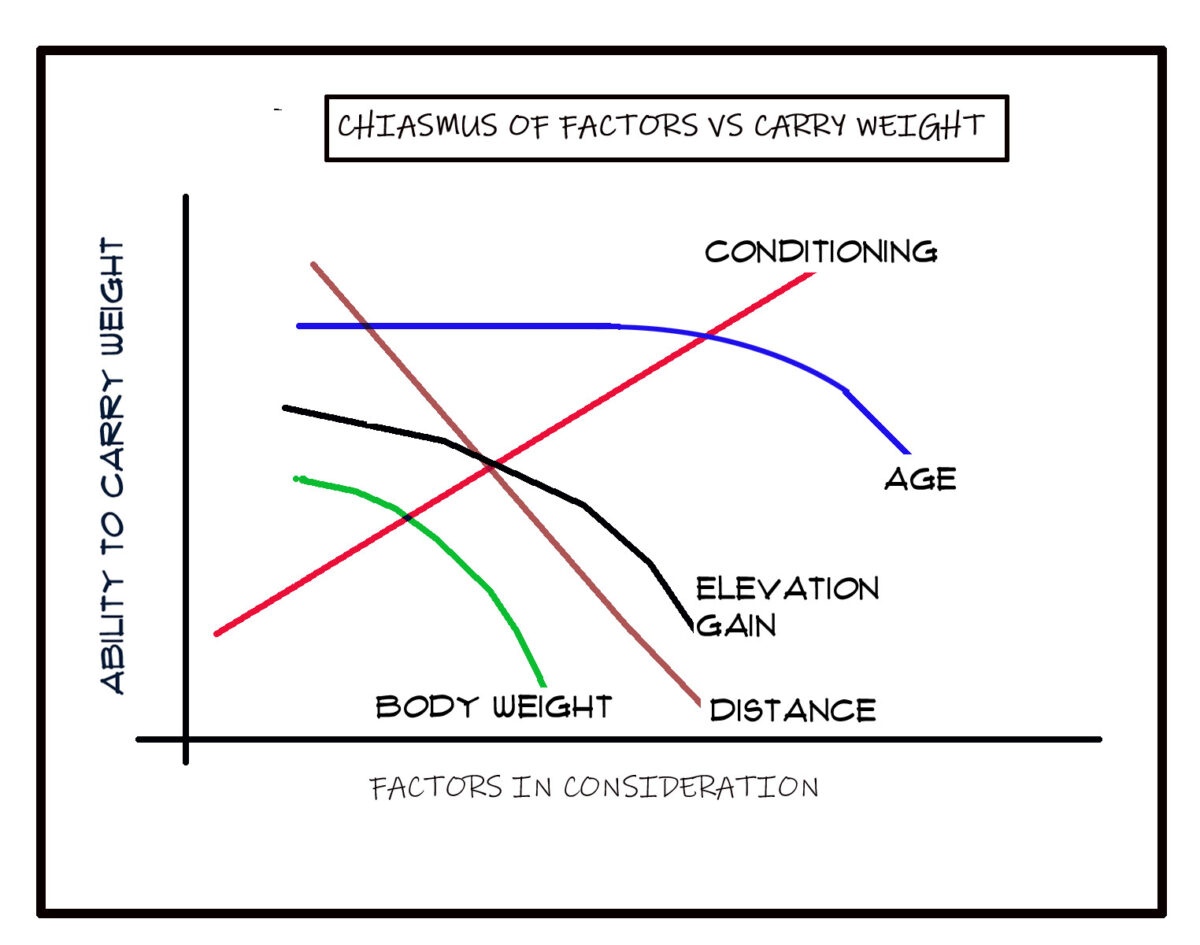

There are many factors that determine how much weight is reasonable to carry in your backpack. A few of the major considerations are your physical conditioning, the distance you plan to travel, the elevation gain, and the environmental conditions such as terrain. There are lots of particulars that differ from hike to hike but those things are certainly substantial when considering the weight you will be carrying.

In 1972 Harvey Manning (Backpacking One Step at a Time) suggested that “experts regularly go for a week in good weather, gentle country carrying only 30-35 pounds.”

He was implying that was a light load and then said that 40 to 50 pounds were more common for a 9-day trip. I also remember reading, at about that time, that 1/5th of your body weight was a comfortable weight for a backpacking trip. So that suggests a 170-pound male could easily carry 34 pounds. That is probably still true, but as I suggested above, there are many things to consider. Certainly, the ultralight gear available today makes it easier to reduce the loaded weight of your backpack substantially. Consider just the tent, backpack, and sleeping bag. I have reduced the total of those three to 3 kilos, or about 6.6 pounds. For just those items, that’s half of what I used to lug around hiking and climbing in the Cascade Mountains when I was young. As Colin Fletcher put it, “[the result is that today we carry] …loads that by old standards are featherweight.”

One thing that is difficult to measure is comfort. And comfort is something I carefully take into consideration on every trip. I can save 4 ounces by taking my lighter-weight sleeping bag. But if there is any chance at all of freezing weather up high I take the heavier bag. I could save 2 ounces on my air mattress, but my heavier one is more comfortable and my good nights sleep is worth it to me. So while I pare away carefully at the weight of almost every item, sometimes a warmer, softer or more durable item is worth its weight. And, really how much more are my 2 ounces of the mattress and 4 ounces of sleeping bag? If you consider body weight and pack weight it is like two-tenths of one percent of the total weight.

And that brings up another subject. How significant are a few ounces or even a pound? Do you really think you will notice the difference? I understand the old saying, “Pay attention to the ounces, and the pounds take care of themselves.” But there can also be a misplaced idea that exact numerical precision is somehow justified. Say you have the ability to carry a 34-pound pack without undue hardship on a particular trip you are planning, but you have now carefully reduced your pack weight to 17 pounds. Is even another pound going to be significant? If you eat better, sleep better, or are better protected from harsh weather the extra weight may even have a positive effect on your enjoyment, safety, and health.

Conditioning

This is huge and I think largely ignored in ultralight backing discussions. If you backpack on a regular basis like once a week you quickly get an idea of your physical fitness. Of course, you can also measure it. What is your BMI? What is your resting pulse? Do you have a training program that includes aerobic and resistance training? Google this; ” How much physical activity do adults need?” Aerobic training significantly improves your capacity to transport and use oxygen in the muscles. Trained muscles have a better capacity to use nutrients. Cardiac output is the most significant improvement when you do regular and intense aerobic training. Some people will object, but I believe that Doctor Cooper’s original book on aerobic conditioning is better researched and supported with references than much of what you see on the internet today. That having been said, using a fraction of your body weight as a guide to your loaded backpack weight is a fallacy because it doesn’t take into account a person who is substantially overweight.

Perhaps, back in the day when they suggested a backpack of 1/5th your body weight they should have said, “1/5th of your body weight when your BMI is between 18 and 25 kg/m².

Your absolute physical conditioning is reduced (I find) with age. Studies show that as a person ages body fat generally increases between ages 30 and 40. At about that age a plot of the times for the marathon for men and women begin to rise at a higher rate. An “inflection point” as it is sometimes called. Regular vigorous physical activity produces physiological improvements no matter what age. However, at a younger age, you can expect a higher rate of improvement. In conclusion, if you don’t have a regular exercise-training program and/or are overweight, you will probably be much better off starting an exercise agenda than spending a hundred dollars to save a few ounces of backpacking gear. It would cost me less to lose a pound of excess fat than to purchase a lighter piece of gear, and I think it would make me feel even better at the end of a long hiking day.

Distance

How far you travel in a day during a backpacking trip should also be factored in when you determine how much you will want to carry. They say when you get to 20 miles in a marathon you are halfway there. Actually, you are three-quarters of the way there, but the last 6 miles are often the toughest part of the race. In my experience hiking, 14 miles seems much further than twice a 7-mile hike. Perhaps it is an exponential relationship of some sort. I’m sure a mathematician could write an equation to model distance vs. effort output. For some people, their feet are a limiting factor. For others, it seems their back starts talking to them at some distance. For most perhaps it is general fatigue. Stopping for rest breaks, taking on water and snacks helps, but regardless the last few miles of a relatively long hike takes a toll. Backpack weight is less of a factor on a relatively short trip, but if you are going what you consider a long distance, then weight becomes much more important. When I hike with people who favor shorter distances each day I am more inclined to take a little extra weight of comfort or convenience.

Elevation Gain

Because I have always seemed to be hiking in the mountains I have noticed, to put it mildly, that gaining elevation takes considerable energy. And the physics of it is rather simple. At least it starts that way. Work and energy have to do with the displacement of an object with mass. So the higher you haul a pack and your body uphill, obviously the more work is done and the more energy is expended. But your ability to do so, both physically and psychologically, is not so nicely measured. When planning a trip you should carefully look at elevation gains, as much or more, than the distances traveled. It should be obvious that this is where pack weight becomes critical. You can break up the elevation gains by camping earlier, but remember the output, from a physics viewpoint is still the same. In conclusion: Weight is less critical when elevation gains are less.

Environment and Terrain

Distance and elevation will be easily looked up in a guidebook or by looking at a topographic map. However, there can be a big difference in what you actually find on the ground. As a friend of mine once said, “there are sure a lot of ups and downs between the 40-foot interval of the contour lines on the map.” Someone else said, “it didn’t look that far on the map.” Some of the trails you hike will be well maintained and on others you may be slowed by climbing over windfalls, walking through creeks, or even stopping to figure out where the trail even goes. A well-maintained trail takes less effort so perhaps a few extra pounds isn’t so critical, but when you have to constantly walk over or around obstacles it is going to take more energy and be more awkward with a heavy pack. Getting a recent trip report or talking to someone who has been there should help you make critical decisions about your pack weight. For example, if I am camping above the tree line I might take a tent instead of a tarp. So your judgment about what is a comfortable weight and what you will “need” will include your conditioning, distance, gain, but also the environment, terrain, and trail conditions.

Conclusion

Perhaps the reason I wrote this is that I see how easy it is to become obsessive about cutting down the pack weight: sometimes unnecessarily, and sometimes at the expense of comfort, safety, and health. I think it should be apparent from what I said, that there is no perfect pack weight, or base weight, that fits all circumstances and people. Every trip and every person differs and we also differ over time.

Home › Forums › Factors that influence the ability to carry Weight in a Backpack