Topic

Case Studies: Using Google Earth to Plan Wilderness Trips

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Home › Forums › Campfire › Editor’s Roundtable › Case Studies: Using Google Earth to Plan Wilderness Trips

- This topic has 5 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated 6 years, 7 months ago by

Luke Schmidt.

Luke Schmidt.

-

AuthorPosts

-

Jun 3, 2018 at 5:02 am #3539937

Companion forum thread to: Case Studies: Using Google Earth to Plan Wilderness Trips

This article presents some case studies of using Google Earth for wilderness trip planning, with a presentation of my process and lessons learned.

Jun 3, 2018 at 3:49 pm #3539968On your #2, I’d add for burn scars you may need to talk with someone familiar with plant (successive) growth. In the western Gila wilderness after a massive burn, a major trail has been cleared (plenty of hunting expeditions), and the various maps (at the ranger stations or online) just show trail/”maintained trail”.

However for hikers, fast growing spiny cats-claws make it rough for hikers unless, as the ranger put it, the hiking party wants to bring pruning shears and I’d add, a machete. It will be this way for the next few years until the trees grow enough canopy where the shade kills the spiny plants. So Goggle Earth is great (even the mobile apps both Mac and Android), but talking to knowledgeable people who’ve been on the ground can be essential to having a decent trip.

Jun 4, 2018 at 1:55 am #3540064Thanks Luke.

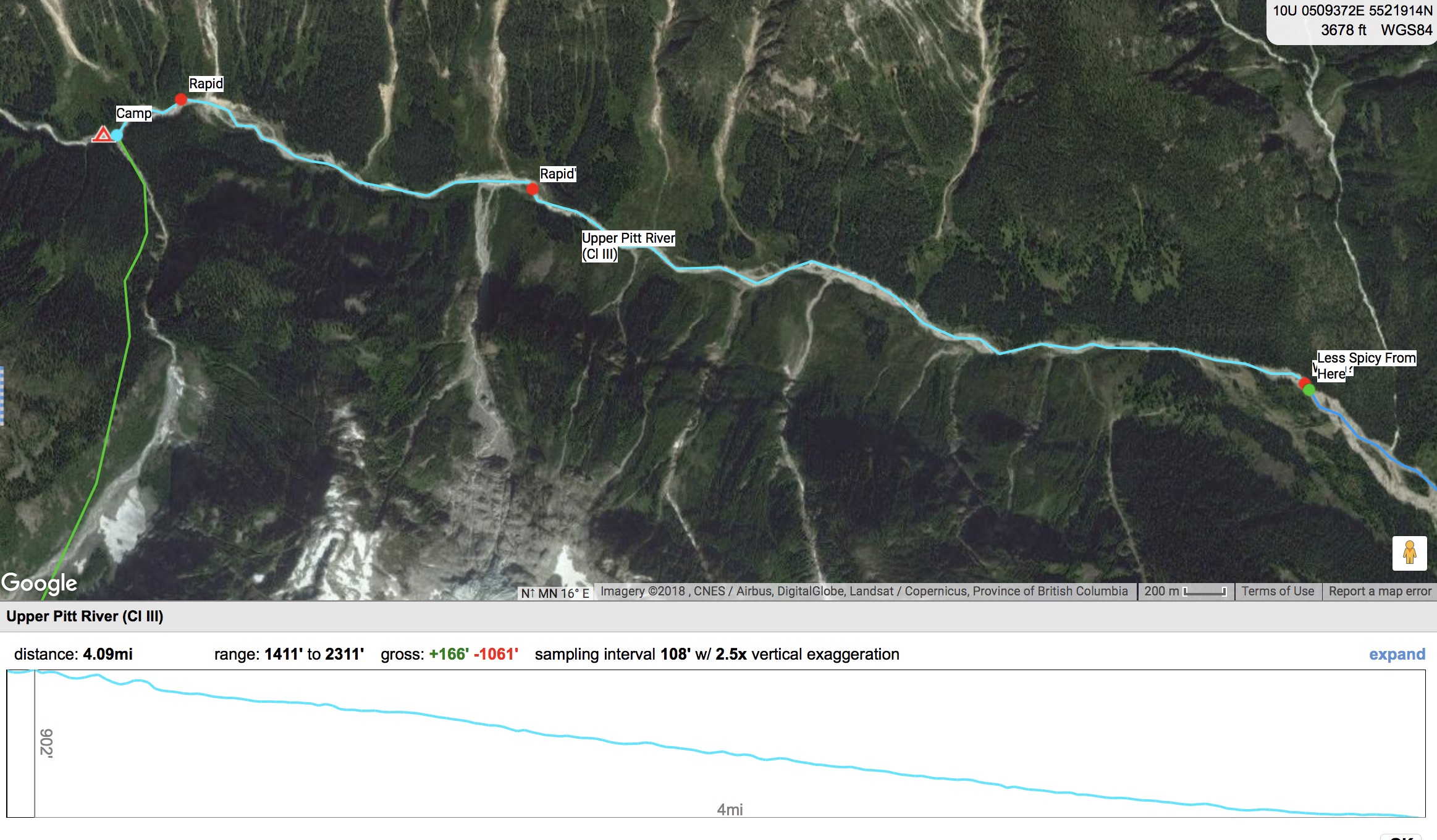

I just took another look at a river I’ve had on my radar. Looks like 225′ feet per mile for the first 4 miles (2300 to 1400′). Hmm….looks like a problem.

But after the first four miles it drops from 225′ per mile to 60′ per mile (aside from that one steep gorge). That might work:

-

This reply was modified 3 years, 8 months ago by

Matthew / BPL.

Matthew / BPL.

Jun 4, 2018 at 6:08 am #3540105Good article, many lessons learned the hard way, which often is the only way that works.

Lots of thoughts on this kind of trip planning:

– Use the Google Earth historical imagery timeline to view photos in different lighting, seasons, and years. Knowing roughly which year that burn happened can help you avoid a suffer fest – or plan on it. A snow-covered scene with late afternoon lighting can show you details invisible at noon in mid-summer.

– Most people (including me) are terrible at interpreting “flat” photos for 3D content. That’s one reason Google Earth combines topography with photos to help you see in 3D. Examine critical points from multiple compass angles and azimuth (vertical) angles. I’ve had many “aha” moments just playing around, even in heavily forested areas where the vertical view is almost uniformly dark green.

– However, combining relatively crude topography (common in forested wilderness areas) with highly detailed air photos can produce weird artifacts and misleading impressions. Google Earth also makes it too easy to fly under or through solid earth without warning.

– You absolutely should compare maps, topography, and images from other reliable sources like Bing maps and local authority maps (e.g. National Park or National Forest maps in USA). Some of them might be available only in paper. The horror!

– Even with the best air photos, topo maps, software, and interpretive skills, you’ll still be surprised. That’s kind of the point in striking off trail or floating rivers with no mile-by-mile trip guide. Plan for extra time, supplies, equipment, and skills to get you out of tough situations. Don’t be afraid to say “let’s turn around and live to play another day.”

– River gradient is very important, but not everything. If it’s over 100 feet per mile, probably big trouble. Anything under needs further investigation.

– For example, the Colorado River through Grand Canyon averages about 8 feet per mile. “Hours of flat water punctuated by 20 seconds of terror,” including some of the biggest rapids in the Southwest. Geology, landforms, and climate are equally important in determining the frequency and difficulty of rapids along a river. More beta is better.

– Don’t be fooled by average gradient over long distances. Some rivers are relatively flat for many miles, before they drop into a short steep gorge, then flatten out again, e.g. California’s Trinity River above and below Class V Burnt Ranch Gorge. If you think “only 40 feet per mile average gradient, we’re good to go,” you might be unhappily surprised. Consider calculating mile-by-mile gradients to be sure.

– As the story mentions, a bright stretch of river could be deadly whitewater, gentle riffles, a boneyard of white rocks – or simply the sun reflecting off flat water. Another reason to look for photos at other times and dates to help you sort it out.

– For some rivers, you can match historical air photos with historical flow information from an upstream or downstream gage, to scope out what the river looks like at different flows. That can help you identify hidden rapids, and plan your trip for the best flows – or the flows you’re stuck with for other reasons.

– Remember, dangerous rapids at low flows can disappear at high flows, and vice versa.

– Rivers change, sometimes in a flash (flood). Always expect the unexpected around the next bend. In the Grand Canyon, Crystal Rapid formed virtually overnight in 1966, changed almost continuously for the first couple of years, changed again in the big floods of the 1980s, and is still one of the most challenging rapids in the Canyon 52 years later.

– As described in the story, one side of a mountain range or ridge doesn’t predict what the other side will be like. Differences in geology, climate, sun exposure, trail development, and many other factors can make a big difference in vegetation, soil, and rockiness.

Hard to imagine John Wesley Powell and company heading down the Green and Colorado rivers in wooden boats rowed backwards, knowing almost nothing about what to expect downstream. That was an adventure in the unknown!

— Rex

Jun 4, 2018 at 6:18 am #3540106Also, if a nearby river has well-known gorges, waterfalls, or major rapids along fault lines, or changes in rock type, etc., you might be able to extrapolate to your river of interest. Often you can trace these features on topo maps, terrain maps, or air photos; a geologic map can help if available. Even if you can’t interpret the symbols on a geologic map, lining up rapids with colors and borders, and following those borders might tell you a lot.

Similar logic might help you scope out difficult cliffs and canyons on land, too.

— Rex

Jun 4, 2018 at 7:12 am #3540112Good thoughts Rex. I haven’t looked at geologic maps but I have noticed that parallel rivers often have for gorges that seem similar at similar elevation. I’d guess the underlying rock is similar.

-

This reply was modified 3 years, 8 months ago by

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Our Community Posts are Moderated

Backpacking Light community posts are moderated and here to foster helpful and positive discussions about lightweight backpacking. Please be mindful of our values and boundaries and review our Community Guidelines prior to posting.

Get the Newsletter

Gear Research & Discovery Tools

- Browse our curated Gear Shop

- See the latest Gear Deals and Sales

- Our Recommendations

- Search for Gear on Sale with the Gear Finder

- Used Gear Swap

- Member Gear Reviews and BPL Gear Review Articles

- Browse by Gear Type or Brand.