Topic

Calling all fuel canister engineers!

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Home › Forums › Gear Forums › Gear (General) › Calling all fuel canister engineers!

- This topic has 86 replies, 12 voices, and was last updated 8 years, 1 month ago by

Roger Caffin.

Roger Caffin.

-

AuthorPosts

-

Dec 18, 2016 at 10:34 am #3440909

Well, we finally received the rudeness of some sub-zero (F) weather here in Boulder. So it was time to play with canister stoves in serious winter conditions (on my patio, where I could easily step inside for a warm drink, and opt to watch bowl games). After confirming once again that my modified Moulder Strip setups work great, and proving once more that more propane in the canister is mo’ better, I ran out of tests to run. So I decided to remove all of the propane from a new/full Optimus 4 oz. canister, so that I could later learn how a mixture of just iso-butane and n-butane would perform (the Optimus fuel is 25% propane, 25% iso-butane, and 50% lowly n-butane).

I used a BRS-3000T stove, and I placed the canister outside on an aluminum side table 3 feet away from my window, where I could watch the action from my lounge chair while I watched the ball games. The temperature went from 0* F to -5*F while I was doing this test, with minimal breeze. According to my rough calculations, iso-butane vaporizes at +2.3* F at my elevation of 5440 feet. So, theoretically, I should have been burning only the propane in the mix, right?

Well, the test went about like I’d expected, with the flame purring nicely as I burned off the propane. At 30 minutes the flame became much less robust, and about half as powerful, and I figured that it was just about out of propane. What surprised me (or rather confused me) was that it stayed that way for another hour. At the 90-minute mark, the flame then reduced to about 25% of the initial propane level, and there was a small yellow flame inside the usual, but weak, blue one. At 120 minutes I shut it down, thinking that something was a bit goofy. After it cooled down I brought it into the house and weighed the canister. There was 1.89 oz. of fuel left in the canister, which I have to assume was all n-butane. It appears that all of the iso-butane had burned off, which totally surprised me.

So I have a question of you learned canister scientists. We all know that a canister cools from the vaporization of the liquid fuel (under summer conditions). But exactly what is the resulting temperature from that vaporization? I assume that the effect is a bit different when propane vaporizes than when iso-butane does. So the question is this: Could the collective vaporization of these fuels actually RAISE the canister temperature when the ambient is 0 to minus 5 degrees F? It seems like something happened to raise the canister temperature to +2-3* F, where it would allow the iso-butane to vaporize (although weakly) and burn off. I need somebody to crunch some hard science numbers to perhaps explain to me how this could have happened (please, no random guessing here, Jerry).

Dec 18, 2016 at 12:40 pm #3440931First of, let’s deal with a common (exceedingly common in the general population that never took a “Separations” course as an undergrad or a graduate-level course all about distillation) misconception:

Namely that: The most volatile (lower-boiling, high vapor pressure) compound completely boils away completely and only then does the next more volatile compound start to boil, etc.

That ain’t true.

It isn’t true that “all the alcohol burns/boils off” when you flambe’ those pears or de-glaze a pan for a red-wine reduction sauce. It isn’t true that all the propane boils off before any of the iso-butane nor that the iso-butane boils away before the n-butane starts to.

The vapors produced during a single-step distillation (in a pot, in a fuel canister, in a fry pan) are richer in the volatile compounds early on and leaner at the end. The mix of vapors has less n-butane at the beginning and more n-butane at the end, but there remains some of each component throughout the canister’s use.

The more disparate the boiling points, the more distinct the separation during distillation. Say, propane and decane – I’m not going to calc it, but if you stopped the process right as the temperature shot up you’d have something like 99.8% of the propane boiled off and 99.6% of the decane left behind. But water/alcohol or propane/iso-butane/n-butane are not hugely different in their boiling points and some of each are boiled off throughout the canister’s use – but richer in propane early on. Hence, proportionally less propane remains behind and canister vapor pressure at any particular temperature decreases, gradually, with use.

So how do the “big boys” do it? How do they achieve high-purity chemical feedstocks? They have a series of individual distillation processes in tall columns. They add heat at the bottom, add the mixture in the middle, and take the low- and high-boiling components off the top and bottom of the column, respectively. Some columns have the equivalent of 20 stages. Some have the equivalent of 100 stages. They don’t bother to do that for fuels – gasoline and diesel are each a range of 200+ hydrocarbons and while they need to have particular vapor pressures, the “cut” doesn’t have to be precise. So those distillation columns are large in their volume capacity but not designed for high purity outputs. Other, much taller, skinner distillation columns are used to, for instance, provide higher-purity benzene as a feedstock for instance to make styrene (and then onto polystyrene and EPS, etc).

Dec 18, 2016 at 1:19 pm #3440932So now, on to your actual questions,

“We all know that a canister cools from the vaporization of the liquid fuel (under summer conditions).”

True. Always true. The “heat of vaporization” is pretty constant, being only a weak function of temperature and pressure. In most of my work, I treat it as a constant (e.g. 970 BTUs/pound of water vaporized) over a wide range of conditions.

“But exactly what is the resulting temperature (drop) from that vaporization?”

To the annoyance of civilized people everywhere, I’ll use English traditional units.

n-butane has a heat of vaporization of 166 BTUs/pound (386 kJ/kg). To boil off a pound of n-butane, and maintain its temperature, you must add 166 BTUs. If you don’t add heat, the canister and fuel in it will cool.

iso-butane’s “Hvap” is 157 BTUs/pound (365 kJ/kg).

propane’s is 184 BTUs/pound (428 kJ/kg).

Those are so close to each other, we’ll take a weighted average of 170 BTUs per pound.

Burn off ALL of a 454-gram canister’s fuel and will lose 170 BTUs of heat because you took a pound of liquid into a pound of gas (and the gas molecules have more energy, flying around at the speed of sound, than those liquid molecules did just bumping into each other).

Okay, so what does losing 170 BTUs of heat do to the canister? It gets damn cold. So cold, it stopped working long ago. But let’s do the calc, anyway. The specific heat of propane and butane are both 0.39 (BTU/pound-F or J/gram-C). The specific heat of the steel in the canister is 0.11. We can almost ignore the steel. So I will. 170 BTU = 0.39 x 1 pound of fuel x temp change of the fuel (in degrees F). That temperature change would be a drop of 436 degrees. Taking you to impossibly low temps, nearly absolute zero. But if you wanted to create some super-lows temps in your garage, er don’t – work outside! But if you insulated that canister really well, and forced it to vaporize the propane/butane by sucking on it with a vacuum pump, inside you’d start getting butane ice crystallizing around -220F in the remaining liquid propane and the propane itself would freeze solid at -306F. And the “cool” thing about that is you’d start getting oxygen condensation (liquid oxygen condensing onto the canister).

In practice two things happen long before that: The canister gets colder than its environment and starts absorbing heat from its surroundings. And as its temperature falls, the evaporation rate and therefore the cooling rate decreases. So it sputters to low level of gas output without ever actually going out.

“Could the collective vaporization of these fuels actually RAISE the canister temperature when the ambient is 0 to minus 5 degrees F?”

No. Vaporization will always be cooling the canister and its contents.

“It seems like something happened to raise the canister temperature to +2-3* F, where it would allow the iso-butane to vaporize (although weakly) and burn off.”

Heat from the surroundings, radiant heat from the flame/hot metal above, conduction through the stove valve stem, and the awesome power of the “Moulder Strip (TM) (R) (C)” are the only things allowing continued vaporization.

Your error lies in the assumption that all the propane is gone when some smaller fraction actually remains. As evidenced by continued vapor pressure above atmospheric at 2F.

Dec 18, 2016 at 2:03 pm #3440938Yes, David is correct. Most miscible substances, say propane and butane, will form a eutectic at some point. Basically it means that in a mixture, trying to distill any fraction out of the mix will result in the same mix being carried over. Or, fractionating a mixture by distillation fails.

Dec 18, 2016 at 2:48 pm #3440950Thanks, guys. David, your lengthy explanation is very much appreciated, and I could stay with you for the most part. The only real-world experience I have had with fractional distillation (outside of my college chemistry classes) was when I lived in Saudi Arabia. We had a good friend, an older guy that was about to retire. He gave us his still that he had since the 1960s, when Aramco (and Saudi Arabia) was much more lenient about ex-pats drinking alcohol. In fact the company actually used to issue stills for the ex-pats to make ethanol with. It was a beautiful machine–stainless steel, large capacity, and lots of gauges, and it came with a detailed manual that told us how to use it, what temperatures all the chemicals boiled at, etc. The recipe called for 50# of sugar, a can of baker’s yeast, and a large plastic trash can full of water. After a few weeks it was ready to distill. It took forever to boil off all the “cats and dogs” (various aldehydes, ketones, and esters, etc. which went directly into the drain) to finally get the temperature to the ethanol boiling point. We would then start collecting the product, and we had to be very careful to be there when the temperature jumped up, which meant all the Et-OH was done, and a new chemical was starting to boil off. The first run yielded about 10 gallons. So after we cleaned the still we did a second run, which was quicker, but not by much. The second run yielded ~ 7 gallons, the 3rd ~ 5.5 gallons, and the 4th (the final run) gave us 5 gallons of very pure ethanol. A 5th run, they say, doesn’t improve anything. The funny thing is that the Brits that lived in the compound would usually stop after the first 3 runs. Man did we ever have weird “cats & dogs” hangovers after the parties they threw!

David, the only thing you said that had me confused was the following:

“But water/alcohol or propane/iso-butane/n-butane are not hugely different in their boiling points…”

With the boiling points being propane (-40* F), iso-butane (+11* F), and butane (+31*), wouldn’t that be considered significant differences? Especially between propane and iso-butane?

We are enjoying a +20* F day today, and I’m letting the rest of that Optimus canister reach ambient temperature. I want to see if there might be enough iso-butane left to jump-start my Moulder Strip setup.

At any rate, I feel like I’ve learned that these canisters can indeed work down to 0* F, at least for a good while. The lower flame output that I witnessed during the last half of last nights test would certainly be capable of boiling water.

Dec 18, 2016 at 4:39 pm #3440961Vaporization will constantly cool the canister.

and heat from the strip will warm the canister

and if the canister gets warmer/cooler than air, then heat will be transfered from/to air to/from canister

those three will balance at some canister temperature.

Like David did, you can calculate the first, but the other two depend on variables not known, but it would be easy for the canister to be a few degrees warmer than air. Like even 10 degree F. That’s the whole purpose of the strip.

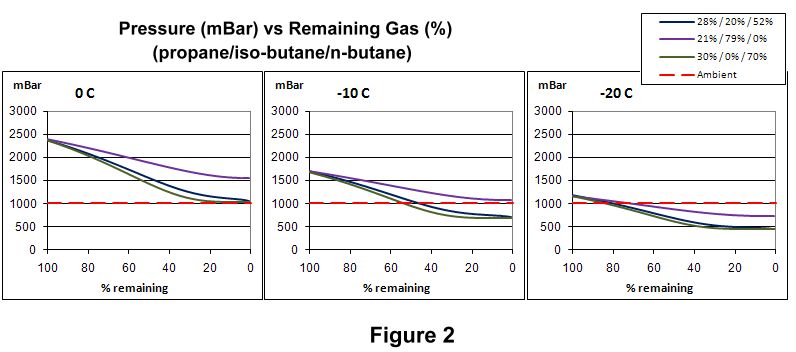

Roger has some charts and formula for how propane gets depleted at different temperatures, fuel ratios, and amount of fuel used. It’s sort of complicated. https://backpackinglight.com/effect_of_cold_on_gas_canisters/

Like look at “Pressure (mbar) vs remaining gas”. -20 C is pretty close to your temp. You can infer from those plots how much the propane gets disipated, like 30%/0%/70% is purple, 15%/0%/85% is red, at 100% fuel remaining there’s maybe 400 mbar beteen the purple and red, at 40% fuel remaining the two curves are pretty close, so most of the propane has disipated.

and you can see from those plots, towards 0% fuel remaining, the two mixtures that have 0% n-butane gradually get close to each other, and the other three mixes with lots of n-butane gradually get close to each other but below the first two curves. Therefore, for cold temperatures, choose a fuel with the smallest amount n-butane.

Dec 18, 2016 at 5:09 pm #3440965Gary,

Those boiling points aren’t far enough apart to achieve a high degree of separation in a single stage. You can see that in “Figure 2” in the 2010 BPL article Jerry cited:

If a high degree of separation was happening, the pressure curve during boil off would be more like stair steps as first the propane boiled off, then the iso-butane. Just as you saw with the jumps in temperature when you were distilling your hooch (in blatant disregard of local mores <smile>): first you saw the more volatile nasty compounds boil off, then a long run of ethanol, then a brief period of less-volatile nastiness before getting primarily water (which remained as the “bottoms”). You saw that more stair-step-like behavior in your still because of the multiple stages – boiling, condensing, and reboiling – going on through the height of the distillation column. And then you went for even better separation by doing repeated runs and tossing the first and last cuts.

Dec 18, 2016 at 7:44 pm #3440979Gary,

Maybe if I word what David and Jerry said a little differently, it would make more sense to you.

Don’t think in terms of boiling points of pure liquids when you have mixtures. You need to look at the partial pressures. Well below the boiling point of n-butane, it still has a vapor pressure. If other components in the mix have a partial pressure that combined with the n-butane vapor pressure is above atmospheric pressure, the canister works and is burning some n-butane. That is what the plots that Jerry sited and David showed are referring to.

I hope that helps and does not make things more confusing.

Cliff

Dec 18, 2016 at 8:13 pm #3440984Thank you David T. You saved me the effort.

To repeat: the assumption that ALL the propane and nothing else will boil off by themselves is common but totally wrong. Moonshiners dream of this idea…

All I will add is that BPL has a quite large range of techie articles on stoves and fuels, and 90% of questions can be fully answered by reading them. Maybe 95%?

Cheers

Dec 18, 2016 at 8:41 pm #344098696.7% of questions can be answered by reading existing BPL articles and posts.

Coincidentally, 96.7% of statistics are made up on the spot.

Dec 18, 2016 at 8:45 pm #3440987yeah, that’s the plot : )

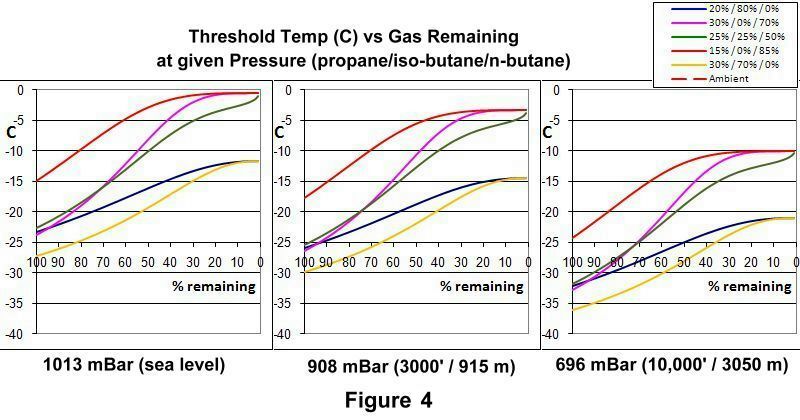

“Threshold Temp vs Gas Remaining…” is another good one

Dec 18, 2016 at 8:57 pm #3440989Your error lies in the assumption that all the propane is gone when some smaller fraction actually remains. As evidenced by continued vapor pressure above atmospheric at 2F.

YES, so as the fuel mixture burns off the relative percentage of propane is reduced but there is going to be some remaining even when the total fuel level is low. One of my early delusions was that the fuel in the can was like a ‘layer cake’ with propane being the top layer.

This is why I was so eager to get the transfer gizmo for straight (granted, with trace amounts of other stuff) N-butane for testing in order to eliminate this effect… to the extent possible for home experimentation, anyway.

Having burned a small truckload of fuel canisters the last 3 years or so in cold and very cold weather, I’ve developed a fairly good feel for how they’re going to burn just knowing the initial fuel mix, the approximate remaining fuel level, ambient temperature and stove setup. The observations and explanations mentioned above mesh very neatly with my experiences.

Dec 18, 2016 at 9:24 pm #3440991according to “Threshold Temp vs Gas Remaining…”

Look at the red plot 15% propane 85% n-butane. At 30% or 40% of fuel remaining, the threshold temp quits raising – in other words, essentially all of the propane is dissipated at that point.

It’s not as bad when there’s more isobutane, because the boiling point of isobutane is closer to propane

Dec 18, 2016 at 10:27 pm #3440996The figure I read was 76.23% …

as quoted by 58.27% of experts.Cheers

Dec 19, 2016 at 5:29 am #3441001The figure I read was 76.23% …

And how many of those stats, in fact, all stats, is decent ? :)

Dec 19, 2016 at 7:47 am #3441010I wonder what the Threshold Temp vs Gas Remaining would look like for 50% isobutane, 50% n-butane

Dec 19, 2016 at 8:13 am #3441014I want to thank all of you for indulging me here. I think I now understand how all of this works (pretty much). With all due respect to partial pressures and eutectics, my takeaway here is this:

- Have as much propane in the canister as possible, with the rest being iso-butane.

- Employ the Moulder Strip when things get really cold.

- If the above don’t work, check into a Holiday Inn Express

(Also, don’t distill your own ethanol–buy Everclear instead)

I greatly admire the collective wisdom of this group, and the willingness to share it. This vastly outshines the clutter of Gear Swap and the crappy BPL software. Thanks again!

Dec 19, 2016 at 10:16 am #3441028“If the above don’t work, check into a Holiday Inn Express”

How timely. I just made reservations for the Fairbanks Holiday Inn Express for Thursday (gotta drill some holes in Fort Wainwright). The forecast low temp is -29F.

BobM: Have you tested your titular strip at that temp? It might be go-go-go and then I’ll be busy all day, but I might be able to stop somewhere along the way and give it a new low-temp test. Somewhere along the 500-mile drive, it may well be even colder than -29F. If so, is there a preferred brand of fuel you’d like to see tested?

Or do you already have the lower-end operating temperature figured out?

Dec 19, 2016 at 10:34 am #3441030David Thomas, you are a gifted educator! Thank you. And thank you to Bob and the rest for chiming in with your expertise.

I teach wine classes (not distillation at least not yet!) and this discussion is a beautiful example of how much you can learn in a forum like this.

And some of it may even be true! kidding…

Dec 19, 2016 at 10:45 am #3441032Do you get a canister to work at all at -29 F? Enough propane? Do you pre-warm it?

Dec 19, 2016 at 10:55 am #3441033Paul, my uncle – a self-taught, high-school grad – started out making fruit wines in his crawl space that he hand-dug into a cellar below his house. He then “graduated” to brandies in collaboration with Saint George’s Spirits in its early days. They began with a single, hand-hammered copper distillation vessel imported from Europe with glass viewports in the column. Apricot brandy was an early success, especially when they put it into chocolate candies. They found that deformed kiwis (the fruits, not the humans nor the birds) could be had for cheap and tried distilling a batch of kiwi wine, but that didn’t prove out. They continue to be pretty experimental in their offerings and have expanded greatly.

Dec 19, 2016 at 11:15 am #3441035

Dec 19, 2016 at 11:15 am #3441035“Do you get a canister to work at all at -29 F? Enough propane? Do you pre-warm it?”

If I pre-chill the canister by strapping it to the roof rack, I expect I’ll to take a Bic lighter out of some body cavity, direct it to the bottom of the canister before lighting the stove, and then allow the Moulder Strip to do its work.

Alternately (or in parallel) I can start with a warm canister and see how low it will go.

Note to self: bring a IR thermometer.

Dec 19, 2016 at 11:27 am #3441036ahhh…

If you get a chance, also try using an aluminum foil reflector. 12 inch square. Under canister. Fold the sides up to reflect the IR from the burner onto the canister.

You may be surprised how well this works.

It never gets cold enough here to do good tests

Dec 19, 2016 at 11:55 am #3441038David, I would dearly love to see that test at -29°F… approaching the limit even for propane.

It’d be interesting to see it done with MSR Iso-Pro fuel with no pre-warming. With a new canister the propane content might be able to get the thermal feedback loop going. Or you could whip out your Bic if necessary. :^)

Straight N-butane would require pre-warming to start, and it would be extremely educational to see if it would continue burning at -29°F. I see no reason why it shouldn’t with a bit of insulation around the canister. Worked fine at -5°F, but actually seeing proof would be fascinating.

Dec 19, 2016 at 1:09 pm #3441051-29 F = -34 C

Propane BP is -42 C or -43 F.

So a straight propane canister would work fine. A propane/n-butane mix would fail. A mix of 30% propane / 70% iso-butane would work above ~1,000 m. Above 3,000m a mix with some n-butane might work for a while. Anyhow, the graphs for this are in the Cold Canisters article.Have pity on the poor old Bic lighter. Put the canister in a bowl of liquid water instead. That works well.

Cheers

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Trail Days Online! 2025 is this week:

Thursday, February 27 through Saturday, March 1 - Registration is Free.

Our Community Posts are Moderated

Backpacking Light community posts are moderated and here to foster helpful and positive discussions about lightweight backpacking. Please be mindful of our values and boundaries and review our Community Guidelines prior to posting.

Get the Newsletter

Gear Research & Discovery Tools

- Browse our curated Gear Shop

- See the latest Gear Deals and Sales

- Our Recommendations

- Search for Gear on Sale with the Gear Finder

- Used Gear Swap

- Member Gear Reviews and BPL Gear Review Articles

- Browse by Gear Type or Brand.