Topic

By the Numbers: How does Tent Design and Materials Influence Cold-Weather Camping Comfort?

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Home › Forums › Campfire › Editor’s Roundtable › By the Numbers: How does Tent Design and Materials Influence Cold-Weather Camping Comfort?

- This topic has 57 replies, 16 voices, and was last updated 4 days, 12 hours ago by

Jerry Adams.

Jerry Adams.

-

AuthorPosts

-

Aug 16, 2024 at 10:41 pm #3816529

Hi George:

I read some of your posts and immediately recognized that you have a lot of years of experience and know what you are doing. We get our data points in whatever ways suit us, and you have undoubtedly gotten yours.

In the scheme of things, we are talking about relative small temperature differences. So, consistency in gathering data and testing setup is critical for useful, repeatable testing. Small differences in methodology will account for small differences in results. That is what we have here.

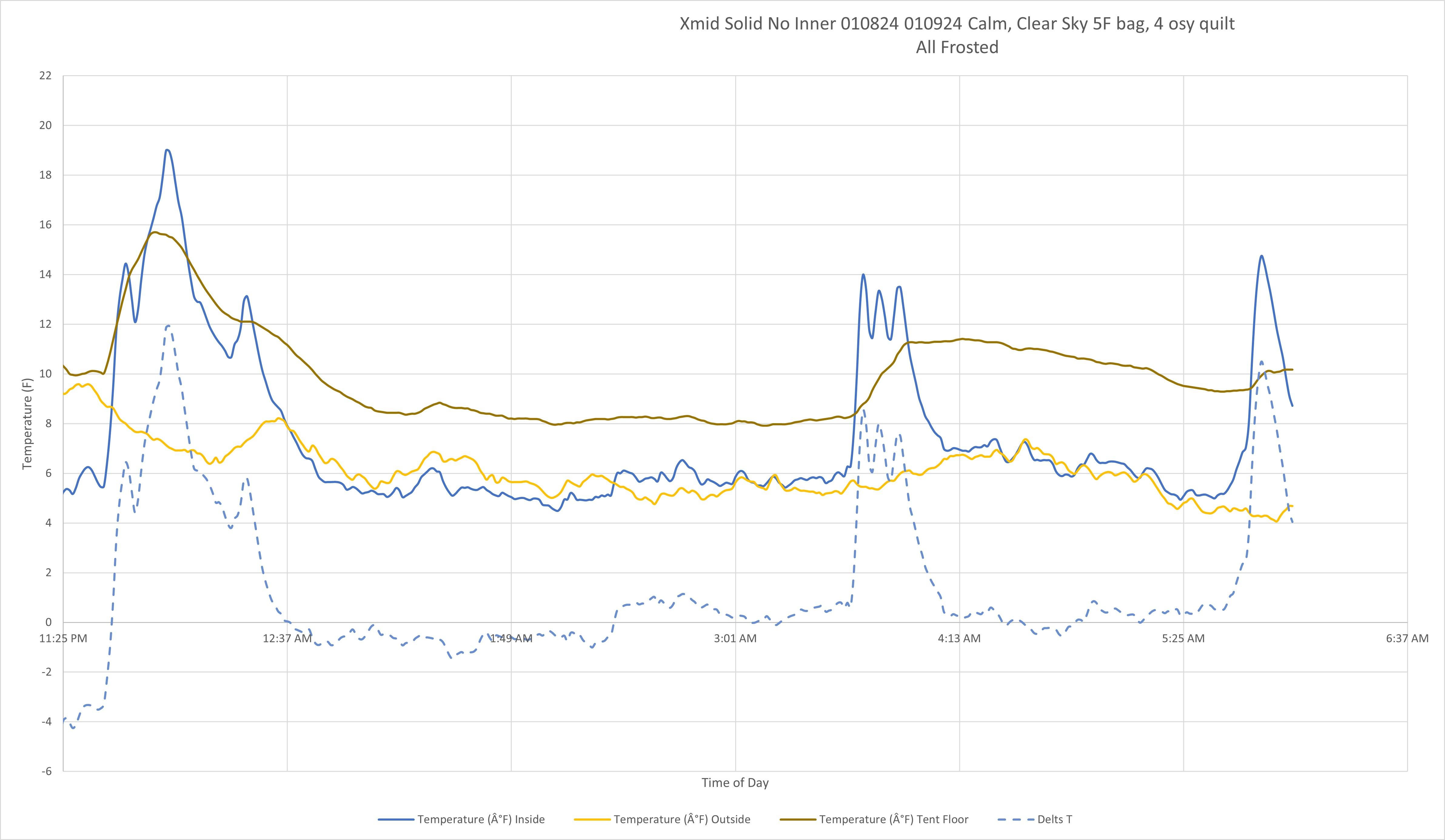

Below, I will repeat the graph of the Durston Xmid 2, without the inner.

The brown line that is added is my tent floor sensor. It is always placed a few inches above the floor at the far diagonal from my head. As you can see, the air temperature is always warmer than what I measured with my interior sensor mounted 2″ below the ridge line. So, you are not wrong, we are comparing apples and oranges. If you had run this test consistently over a range of tents you may have reached the same conclusions that I did, just with different temperature differences from outside ambient.

Another point, as you go forward. Do not trust factory calibrations on instruments that are too cheap to calibrate at the factory. I calibrate my tent sensors against other sensors that are factory calibrated every year. I then use offsets for the factory settings of my blue tooth sensors so I know all the sensor readings are comparable. You probably cannot do this, but what you can do if your sensors offer offset capability is simply designate one sensor interior and one sensor exterior and set one to replicate the other. Do this in the sort of temperature range you are taking data in. This should make your readings pretty repeatable between the two sensors. If you do this type of calibration, let the sensors sit in the same ambient for at least an hour before determining your offset. If the blue tooth signal can escape a refrigerator, that is where you might want to put them for the matching process.

I was not aware of the sensors you used. They are dirt cheap. I hope others reading this will start instrumenting their tents and keeping track of their methods and conditions. I like using an interior sensor just to help me regulate ventilation in my tent to avoid condensation.

I look forward to seeing the data that you collect this winter in your tents.

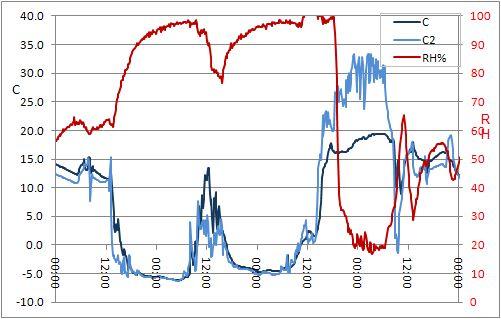

Aug 17, 2024 at 12:15 am #3816534Data from a trip some years ago, taken over several days.

Nights 1 and 2 were obviously sub-zero, but with high humidity. A feature of Australian snow fields. Night 3 was in a shelter. and the humidity crashed for some reason – maybe because it was so warm.

Cheers

Aug 17, 2024 at 7:41 am #3816546a cheap way to calibrate your sensors

take a probe thermometer for cooking

put it in a glass full of ice, with water added to fill the voids. Put the probe in the center. Stir it up. Then wait for the temperature to stabilize. Write that temp on the thermometer, for example “33”. Then, manually add the offset, in this case “1” to each reading.

Then use that to calibrate any other thermometers – put them in a place where the temperature isn’t changing.

Actually, you can skip the absolute calibration – put several thermometers in a place where the temperature isn’t changing. Assume one is correct and find the offset for the other thermometers to match. All you care about is temperature differences.

Aug 17, 2024 at 8:55 am #3816555Hi Roger:

I don’t know if I am interpreting your data properly. It appears you logged data continuously, not just while in your tent. Are the two blue lines interior and exterior temperature? Is the red line interior or exterior humidity? I would guess it is interior. If the two blue lines are interior and exterior temperature, they look very close to one another, especially during the hours you were likely sleeping. This would appear to agree with my experience. Of course, the exception is your night in the shelter.

Where did you mount your interior and exterior sensors?

I presume your tent interior got frosted at night since the humidity reached around 100% on the first two nights.

Aug 17, 2024 at 4:29 pm #3816588Hi Stephen

It appears you logged data continuously, not just while in your tent.

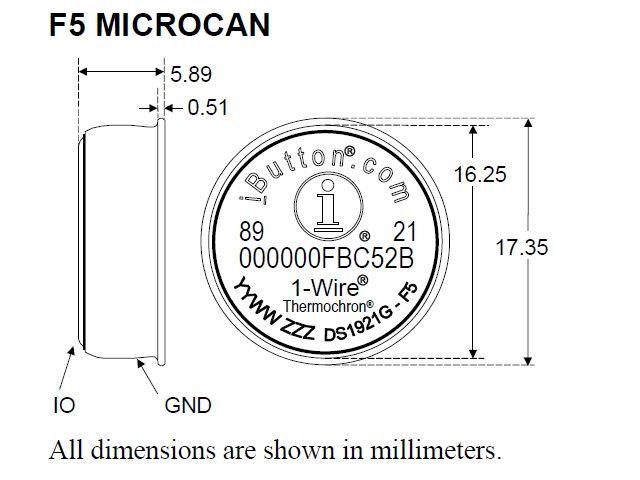

Yes. The tiny button-shaped Maxim Thermochron sensors are programmed from the PC before the trip. So they run continuously. They use Maxim’s One-Wire signalling: pre-USB. Tricky stuff, but really small.

Are the two blue lines interior and exterior temperature?

No, both inside. I hung one up near the top of the tent at the ridgeline and one low-down at about sleeping head-level inside the tent. Why? I had two of them – they were freebie samples from Maxim.Is the red line interior or exterior humidity?

Interior. One of the Thermochrons sensed both temperature and humidity.I presume your tent interior got frosted at night

Yeah! Hence my comment about getting frost down the back of my neck when I sat up.I still have the Thermochrons, but I suspect the internal batteries are by now flat. Very old.

Cheers

Aug 17, 2024 at 7:47 pm #3816595I’m still uncertain about the parameters meant in “cold weather camping’. Snow camping in winter? I have no experience with that. Early and late camping at altitude? That I know.I haven’t done any measurements with instruments. I have however spent hundreds of nights at elevation in a variety of tents. My mere experiential impressions? reduced to two out of many:

–a Zpacks single wall hexamid solo tent was instantly recognized as being colder than any of my previous tents. Indeed, that was the first thing I noticed about it. The inability to bring the front beak down near the ground and the resultant wind/circulation was part of that

–a double wall tent with panels instead of mesh helps block wind and retain interior warmth. Mostly the wind blockage helps, imo.

All of the measurements mentioned above come with caveats and hedges and ifs ands and buts. Real life conditions in the wild aren’t replicable as in a lab. No one in the scientific community would take these measurements as confirming anything because the variations of conditions and measuring instruments and all the rest are too wildly…wild. too many variables to “scientifically” prove or disprove the stated aim.

And so we’re thrown back on our own real world experience. Phew! Isn’t that why we go out into the wild to begin with?

p.s. John Muir was a scientist as well as a poetic observer of wilderness. It’s possible to be both, obviously. But then Muir’s theories regarding geology in the Sierra, that went against standard scientific theories of his age, proved to be correct. No measurements involved! Merely a keen eye and a ton of experience.

Aug 17, 2024 at 9:59 pm #3816596disregard my post above. I was able to read the free preview and realized this article concerned issues beyond my purview. Well done! carry on.

Aug 18, 2024 at 8:14 pm #3816629So is the next great tent fabric Dyneema laminated to a reflective film on the inside?

Aug 20, 2024 at 11:16 am #3816725Another deep thought article that I appreciate so much. I have a spent more than a few winter nights in a tent. Your days are short so if your not a night hiker, you spend a lot of time in your tent. I can tell you for sure, a single wall tent or a three season 2 walled tent is a lot more draftier on a windy ridge than a 2 walled 4 season tent which translates into colder for the occupant. Maybe it can’t be measured in degrees but it sure feels it in discomfort.

Aug 21, 2024 at 4:02 am #3816781The only observation I can add is I have witnessed many times frozen condensation on the inside of the fly, but none on the solid fabric of the inner.

Does this mean that the fly material is colder than the inner?

Aug 21, 2024 at 10:53 am #3816791Scott Chandler: So is the next great tent fabric Dyneema laminated to a reflective film on the inside?

Aug 21, 2024 at 4:56 pm #3816799

Aug 21, 2024 at 4:56 pm #3816799I have witnessed many times frozen condensation on the inside of the fly, but none on the solid fabric of the inner.

Does this mean that the fly material is colder than the inner?

Exactly.

Assume the fly is at -5 C, and that the top surface of your quilt is at +15 C.

Then the inner tent might be around +5 C: halfway in between them. Very rough, but it gives the idea.Note: this does not apply if the inner ‘tent’ is just mesh. Air exchange goes straight through mesh. The inner does have to block airflow to be useful. Mind you, some through-ventilation is still desirable.

Now, what happens if some frost falls off the fly – wind maybe? Some of it will fall to the ground, and some of it will land on the inner fabric. The latter part will melt since the inner is above 0 C, and run off to the ground – given some degree of DWR treatment on the fabric. Well, that is a whole lot better than landing on your quilt and melting there!

Cheers

Aug 21, 2024 at 6:47 pm #3816809Hi Gordon and Jeff:

These observations are interesting, but without knowing anything about weather conditions, conditions in tents, and the type of tent, we don’t really learn anything about the impact of tent construction or design on interior comfort. If you can be more specific about describing any of these data points, that would be helpful.

I just looked back at my data from November to early February. I did not go through February-April on this round. In addition to all the instrumented data, I recorded frost on the fly and, if a double wall, the inner. The inner is always solid. I used three solid wall tents: Durston Xmid 1 and 2 and a Dipole 1. I was in the double wall tents on eight nights during this period. On 7 of 8 nights I had frost on both tent walls. So, we know that on 7 or 8 nights, both tent wall surfaces were below the dew point. On one night, the inner tent surface was above the dew point. Throughout the winter, I typically had frost on both surfaces when frost was forming.

If you can describe the tents involved and any further information, that would be useful.

Like everything else, the impact of high winds can be complex. Jeff, perhaps you can identify the single-wall and double-wall three-season tents and the four-season tent and what features might have made the former more susceptible to wind. Also, was your sleeping bag warm enough for the temperatures encountered in the three-season tents? Did you have a warmer bag in the four-season tent? How did wind speeds vary for those experiences? I know these are hard to remember, but they can help us develop useful information.

Aug 26, 2024 at 11:38 am #3817014Interesting article. I’m worried that the IR thermal imaging method aren’t very accurate. For objectives having low emisssivity (ie below 85%) the transmitted as well as reflected IR energy will heavily influence your results.

Aug 26, 2024 at 11:53 am #3817015Hi Kristoffer: You are right, so I take several measures to ensure reasonably accurate measurements. Looking at some of the images, you will see round paper stickers or electrical tape attached to the surfaces I am measuring. Similar techniques are used in the article you cited. Using high-emissivity coatings for objects with low emissivity or high transmissivity is essential to measuring the tent walls’ actual temperature, emissivity, transmissivity, or reflectivity.

Aug 26, 2024 at 10:06 pm #3817032Thanks for clarifying!

Sep 12, 2024 at 8:13 am #3817994In that other thread I thought DCF tent would be as much as 10F colder

In your table 4, “Results of the Simulated Sleeping Bag Radiant Heat Transfer Comparison Test”, the “Bag Surface Maximum Temperature Drop” was

Dyneema – 13.4F

Polyester – 10.3F

2 layer polyester – 8F

If I compared to a tent with a radiant barrier, I would need a sleeping bag that was this much warmer to stay comfortable

Comparing Dyneema to polyester, I would need a sleeping bag that was 3.1F warmer to stay the same comfort

Am I interpreting this correctly? Isn’t this the number of interest?

And there’s an additional 2.3F for a 2 layer polyester tent. So, somewhat contradictory to the idea that 2 layer tents aren’t useful which I concluded from the comments above. 2 layer tents do offer some warmth.

One interpretation of this would be dyneema tents are inferior. Another interpretation would be the temperature differences were so small as to be insignificant.

Is DCF and dyneema the same in this regard?

In table 4 I noticed the ambient temp dropped from DCF to polyester to 2 layer polyester. I wonder if this affected the results.

Sep 12, 2024 at 6:01 pm #38180222 layer tents do offer some warmth.

Having spent many nights camped in the snow in one of our double-skin tents, I can surely agree.

Although we would put it as being about 5 C warmer.

In some detail: the nearly still air in a good double-skin tent really makes a difference too.Cheers

Sep 12, 2024 at 6:18 pm #3818023Hi Jerry:

One of the key things I learned in doing the tent research is that tent comfort is the sum of all available heat loss/gain mechanisms in your tent. Concentrating on a single heat transfer mechanism isn’t going to allow you to predict your inside tent temperature or your comfort.

Your question assumes that the bag’s surface temperature is somehow related to how warm the bag must be to keep you warm. There may be a relationship, I suppose, but indirectly. The temperature of the bag surface is a function of the air temperature around the bag’s top surface, the temperature inside the bag, the ground temperature, the sleeping pad warmth, the radiant temperature of the tent walls, the R-value of the bag’s insulation, and more. It is a very complicated thermal problem to figure all of this out, and this is not the problem I try to solve in Table 4. The problem I am trying to solve is how much additional energy the person in the sleeping bag loses in response to changes in the IR transmission of the tent.

The sleeping bag comfort rating test never measures a sleeping bag’s surface temperature. However, like mine, it does measure the steady state watts needed to maintain temperature under a single condition and then uses energy balance calculations to extrapolate to other conditions while sleeping on an R4.8 sleeping pad.

I am using a simulated sleeping bag to measure the change in energy expenditure by the sleeping bag inhabitant in watts or calories when sleeping in an R5 sleeping bag in tents with varying IR transmissivity. The test results tell us that energy expenditure increases with tent IR transmissivity. However, it turns out that the tent’s IR transmission performance simply does not matter much when you are in a sleeping bag that is correctly rated for the conditions.

There are three lines in table 4 that describe the performance: “Increased heat loss of Typical Male due to Radiant Heat Loss (W/hr)”, “Food KCalories to Offset Additional Energy Loss at 75% Conversion Efficiency for 8 Hours”, and “Girl Scout Thin Mint Equivalent To Offset Energy Loss”. The easiest to comprehend is the Girl Scout Thin Mint Metric. As we can see from these metrics, the additional energy losses are the equivalent, at worst, of a couple of Girl Scout Cookies consumed over 8 hours.

To help put this into perspective, look at the Watts/Ft2 metric in table 4, at .81, .44 and .37. Compare this to what we measure in the simulated skin test. This test asks what happens when tent IR transmissivity changes when you are lying naked in your tent. Those equivalent Watts/Ft2 are 8.6 and 2.9. In this case, the person sleeping in the Dyneema tent would have to eat about 224 Girl Scout Cookies. The person in the single wall Polyester tent would have to heat about 77 Girl Scout Cookies. So, in an extreme case, IR transmission matters greatly.

I hope these simple comparisons convey the orders of magnitude involved and the critical importance of a properly rated sleeping bag.

To the extent that my test results can be extrapolated, the answer to your last question is that yes, tent construction and fabrics can produce interior air temperature differences in tents. However, the totality of heat transfer mechanisms at work in your tent means that those differences will be minor. Your tent will tend to stay within a few degrees of outside ambient temperature, regardless of number of tent walls or fabric type. Can you reduce your sleeping bag weight by a pound if your second tent wall adds a pound? The answer, from my data, is no. This is because your extra tent wall might add a couple of degrees of interior warmth. That extra warmth will not allow you to carry a lighter sleep system.

I hope this helps. If you have more questions, send them along.

Sep 12, 2024 at 6:32 pm #3818026Hi Roger: I hope what I posted above helps clarify things. I must point out that your tents have two heat sources. I don’t know how you do it, but I have not convinced my wife to participate in my tent testing! So, unfortunately, I only have one heat source for my tests.

Perhaps if you find yourself out in the cold, you can try the same measurement techniques I am using and compare results. I am betting that your double-wall tent might be 4F above outside ambient with the second heat source.

Sep 12, 2024 at 6:44 pm #3818027Hi Stephen

your tents have two heat sources.

Yeah, good point. We are conscious of the benefits too.How to get this? Marry the right girl. :)

Cheers

Sep 12, 2024 at 8:09 pm #3818032I like your thin mint equivalent because that’s intuitive. That’s how much more you’ll have to eat to make up for the colder bag/tent/conditions

When I sleep, sometimes I’ll get cold. If it’s just a little, but I can still sleep good, that’s my goal. I think that’s like the “comfort limit” in en 13537.

I want to avoid being colder than that. If I’m warmer than that, I’m okay. I can unzip if needed.

I think the surface temperature of the sleeping bag is what’s key. Given that, you can just use the en 13537 comfort limit. You don’t have to worry about wind, or IR, or your tent, or anything.

That’s why the surface temperatures in your table 4 are what’s important.

What’s confusing about the thin mints is that en 13537 assumes a particular MET. Your body produces a specific number of watts. If you’re cold, you can’t just produce more watts, metabolize more thin mints.

Maybe this is in incorrect assumption by en 13537 or my understanding of it.

Sep 12, 2024 at 8:13 pm #3818033Maybe if you get colder than the comfort limit, your body can produce more watts, but that will make you uncomfortable. For example you start shivering or wake up and start moving around.

Sep 13, 2024 at 4:45 pm #3818069I saw this with the google

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232852/

it says that if you get cold, you will redirect blood flow from your arms and legs to keep your torso and head warm. And you can exercise to produce more heat, but that doesn’t help when you’re sleeping. Or you can shiver but it’s uncomfortable to shiver while sleeping.

but “Certain animals respond to cold exposure with an increase in metabolic heat production by noncontracting tissue, a process referred to as nonshivering thermogenesis (LeBlanc et al., 1967). However, there is no clear evidence that humans share this mechanism (Toner and McArdle, 1988).”

Other, less sciencey sources have said the opposite, that you can burn more calories if you get cold.

so eating more thin mints is not such a useful idea.

(This is not about whose right and whose wrong, I’m just trying to figure this out because its an interesting, complicated problem. Your articles have helped me to understand all of this better…)

Sep 13, 2024 at 4:59 pm #3818070so eating more thin mints is not such a useful idea.

But they might be very tasty?

Do they have chocolate?Cheers

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Trail Days Online! 2025 is this week:

Thursday, February 27 through Saturday, March 1 - Registration is Free.

Our Community Posts are Moderated

Backpacking Light community posts are moderated and here to foster helpful and positive discussions about lightweight backpacking. Please be mindful of our values and boundaries and review our Community Guidelines prior to posting.

Get the Newsletter

Gear Research & Discovery Tools

- Browse our curated Gear Shop

- See the latest Gear Deals and Sales

- Our Recommendations

- Search for Gear on Sale with the Gear Finder

- Used Gear Swap

- Member Gear Reviews and BPL Gear Review Articles

- Browse by Gear Type or Brand.