Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument sits uneasily on the borderlands of southwest Arizona. It is very much a frontier; being a conjunction of nations, cultures, and ecotones. It is home to plants and animals found nowhere else in the US and is rightly designated a UNESCO biosphere reserve. It also hosts some of the darkest skies in the country. I hoped it would be a perfect setting to observe a recent Super Blue Blood lunar eclipse.

Backcountry trips in Organ Pipe require a permit, available in-person at the Kris Eggle Visitor Center. My plan to hike a five-day fifty-mile (80 km) loop through the Monument caused a bit of consternation there. As the rangers puzzled over my proposal to hike multiple backcountry zones, I looked over the permit log. No one had obtained a permit for weeks, and the few permits that were issued were for overnight out-and-backs. Eventually, the rangers concluded that multi-zone multi-day trips are not actually prohibited. They gave me a permit to leave my car at a trailhead and wished me well.

As they should. The Organ Pipe backcountry is not truly under the control of the US Government. It was closed from 2003-2014 after the murder of Ranger Eggle by drug-smuggling fugitives. Although now deemed safe enough for backpackers, the Monument still sees significant traffic from smugglers and migrants.

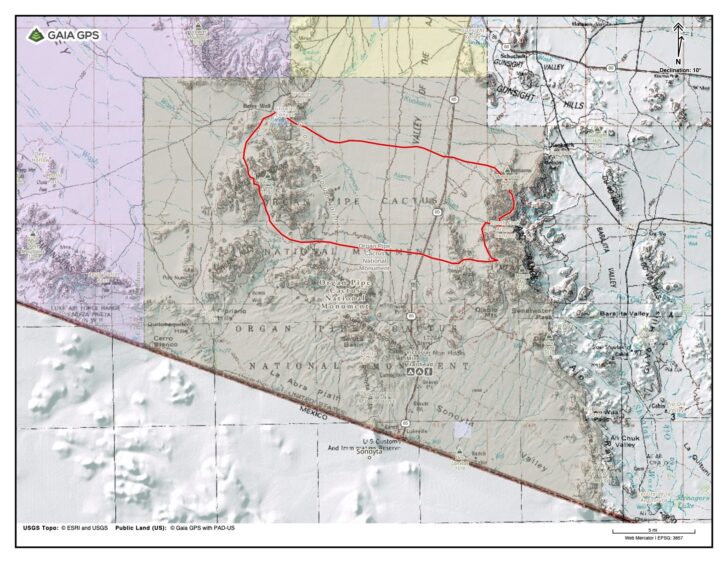

My planned route would take me north through the Ajo Mountains, then west across the alluvial plain of the Ajo Valley, through and behind and then back over the Bates Mountains on the west side of the Monument. I would return east across the southern Ajo Valley and over the Diablo Range. There are no designated or maintained trails in this region. There is no water.

Into the Desert

With only a few hours of daylight remaining after caching water and securing my permit, I parked my car, saddled up, and crossed the low pass separating Arch Rock Canyon from Alamo Canyon. I made camp at dusk a few hundred yards beyond the car campground at its mouth, only slightly bloodied by the hurried bushwhack. I did discover a bandana missing, presumably the work of a larcenous jacaranda.

An exquisite sunset ended the day with a promise of desert beauty to come. I rejoiced to find myself back in my native country and settled in to sleep on its accommodating sands.

Around midnight I awoke to the sounds of cars pulling up nearby. Voices conferred in relaxed Spanish and then faded into the distance. A couple of hours later the voices returned and the cars departed.

Faced with a long rocky route and a shortage of January daylight, I was up and out of camp well before dawn. A mile up the canyon I discovered the likely work of the night visitors—gallon jugs of water and a bucket of food. They were stashed for migrants who dared travel a route too wild and rugged for La Migra to follow. Tucked under a large boulder, the jugs were inscribed with slogans like “vaya con la virgén” and “chinga la migra.”

The route up the canyon, more scramble than hike, was well-marked by the passing of the migrants. Socks, sneakers, clothes, and above all, foil tuna packets lined the canyon bottom and showed the way north. Although not marked on any map, I was clearly following a trail. El Sendero Atún I called it.

It was a hard route. The top miles are a continual rock scramble, much worse on the way down than on the way up. I did enough butt scootching to wear holes in my pants. My poor plastic ukulele took a beating too.

I moved slowly and carefully. I was out of shape. There was no phone service. No one knew exactly where I was, or when to expect me. Anyone else traveling this canyon would have little interest in contacting the authorities to arrange a rescue. If I fell or pulled a rock down on myself I’d be in big trouble.

After the scramble down the north side of the divide, I finally reached the desert floor, its alluvial slope a garden of saguaro, prickly pear, and cholla. Oddly, there were no organ pipes on this side of the mountain. I crossed the highway and struck out across the desert pavement, heading for the setting sun. There was an open spot on the gravelly plain and I made it my cowboy camp and lunar observation post.

Though cloudy at sunset, the skies cleared at midnight, and I was rewarded by open views of a baleful moon over the Bates Range to the west. On cue, a pair of coyotes began howling as totality began. I sat entranced by the spectacle, quilt wrapped around my shoulders, watching the moon shade from bone to bark to blood as it slid behind the Earth’s shadow.

I was not alone.

In a mesquite-lined wash a quarter-mile to the south a light flashed: five seconds on, five seconds off. The signal continued until met by an answering light further down the wash. The lights approached each other, converged, then disappeared. Who were they? And where were they, and where were they headed?

I turned off my camera lest its lights and beeps give me away. In all likelihood, the nightwalkers would be more frightened of me than I of them. But I couldn’t know this. I kept my eyes on the blood moon, but my ears were alert for the sound of approaching visitors.

The moon slowly brightened and then dropped behind the mountains. No one passed near. I lay back and slept.

Contenders for Land

Arising at dawn, I strode west through the widely spaced creosotes, my progress rapid and untroubled. Navigation was simple: head toward the gap in the mountains to the west-northwest. I crossed the tracks of the coyote songsters and then another migrant trail, this one marked by black plastic jugs. Most of them were cut up and shaped into funnels and scoops. Helicopters passed low overhead, several converging at the southern end of the Bates Range. One circled above me for a minute, then left, perhaps deciding that anyone walking west in the open in broad daylight was not suspicious. Although this area is a designated wilderness, there were numerous jeep tracks made by the Border Patrol. (Editor’s note: CBP officers are allowed to use vehicles for pursuit, but they are legally prohibited from using vehicles for surveillance here.)

But the desert held its share of delights and wonders. The shells of desert millipedes in the sand evoked a day at the beach.

I paused to examine an eight-foot shrub with the largest, wickedest thorns I have ever seen. It was Emory’s Crucifixion-Thorn (Castela emoryi), found only in the lower Sonoran and Mojave deserts.

A movement to my right betrayed the presence of a deer steadily trotting away from me. Looking closer I saw that its head was oddly shaped, resembling neither a muley nor a whitetail. I realized it was no deer—deer usually bound away from threats rather than trot—but a Sonoran pronghorn, one of maybe a dozen in the monument, of a few hundred in the world.

Growler Canyon, my path through the Bates Range, was a sandy wash churned up by the contenders for this land—smugglers, Border Patrollers, and rogue ATVers. Although the grade was nearly level, my pace was slowed by the soft deep gravel. I passed a well-established but deserted migrant campsite and collected my water cache at Bates Ranch. I hesitated, then decided to leave a couple of liters for the next passers-by, whomever they should be.

The abandoned ranch is strewn with ancient rusting settler trash. The cans, bottles, and broken implements were left here by people—themselves migrants—who lived a hard life and did what they felt necessary to survive. Keeping the landscape tidy was not high on their list of priorities. Those cans are now old enough to be considered historic artifacts rather than litter, worthy of an admiring informational kiosk constructed for the edification of jeep tourists. Its readers might be forgiven for believing that the history of this land begins with the advent of Anglo settlers. There is no mention of the original inhabitants, the Tohono O’odham.

Kino Peak, the apex of the Bates Range, towered above. It looked down on the ranch with the austere timeless indifference of desert peaks. Its walls were naked of vegetation, the volcanic plug a skeletal remnant of creation. It will remain while we humans come and then go.

I skirted the west side of the range, diving in and out of small canyons, walking against the alluvial grain. As I turned up the bajada that would carry me to the crest of the range, the signs of migrants—that is, their litter—became abundant once again. Not wishing to encounter more nightwalkers, I camped in a discreet side valley under the shelter of Kino Peak. I was comforted by its mass and warmth as it radiated back the setting sun. I quietly sipped my whiskey while my ukulele remained unplayed.

An uneventful night brought a warming dawn, the temperature climbing as I made my way up the steep slopes of the range. Views of an even-harsher land, the Cabeza Prieta, unfolded to the west. An intense blast of sunlight—and more trash—at the saddle left me disinclined to linger. I opted to follow a rocky ridgeline rather than a brushy gully down to the desert floor. There I joined a broad canyon thick with saguaros and followed it to the southern end of the range. Weaving among volcanic outcrops, I struck east across the Ajo Valley.

Desert washes—steep-sided, deep, and filled with thorny mesquites, jacarandas, and palos verdes—provided both the only obstacles to navigation and the only refuge from the sun. In true hiker fashion, I cursed the thorns but took advantage of the shade. Out on the open plain again, my windswept camp afforded fine views of the last rays of sun lighting up the Diablo Range to the east.

An Odyssey Concludes

The next morning I enjoyed a rosy-fingered dawn over the Diablos (I was reading Emily Wilson’s terrific translation of The Odyssey), and then picked my way through a low saddle in the range and down to my car. I felt gratified but unsettled. The hike was all that a lover of desert landscapes could want—stately cacti, sun-blasted peaks, secret canyons.

But those canyons were not such a secret. Although a site of recreation for me, they were the locus of suffering and struggle for others. I blithely strolled where fellow humans, unprepared or betrayed, had breathed their last. The remains of more than 20 migrants were found in the Monument in 2018.

How do I deal with that? How should I deal with it?

I resent having to ask the question.

These lands are set aside for the enjoyment of all. They are my lands. I was born and raised nearby. I have every right to walk here unhindered.

I can’t fault those seeking a better life for themselves and their families. But I resent having to worry if moving lights at night are a threat. I resent having to find campsites hidden from illicit pathways. And I really resent the skeins of trash that defile this land—my land. It feels like a palpable mark of disrespect, a big “F*** you” from uninvited guests.

I have the luxury of feeling that way because I don’t have to worry about feeding my family or fleeing from violence. I am safe, well-fed, and comfortable. None of the migrants who drop empty water bottles in the desert came here for fun. They were trying to survive, and survival is the most fundamental and undeniable right of all. We cannot lock families in cages, or persecute those who would rescue them, for exercising this right.

You might think that none of this has anything to do with backpacking, and may perhaps wish that I would just stick to telling inspiring hiking stories framed by beautiful pictures.

I would like nothing better. But abuse of people is inextricably entwined with abuse of the land. If we do not object to people being caged we can hardly object to walls that cut off wildlife corridors and separate tribes, or construction that destroys vital springs, or the incursion of motorized vehicles into the wilderness.

Humans and the natural world are not separable. We can treat both with respect, or we can objectify, exploit, and destroy both. The desert is not a cactus Disneyland, carefully walled off from the reality that surrounds it.

We can’t just walk; we have to talk.

Editor’s Note: If you’d like to share your borderland backpacking experience with us, we’d love to hear it. Send your perspective to [email protected] for possible inclusion in a future blog post.

Related Content

- More by Drew Smith

- Read more desert stories from Ben Kilbourne and Andrew Marshall