Prior to moving to Montana from my sanitized life on the East coast, the majority of my outdoor recreation involved out-and-back day hikes with plenty of signage and an ice cream cone on the way home. I was fit and enthusiastic but had yet to experience the range of activities that existed from access points my sports car couldn’t reach.

At 23, I was new to the West and eager to shed my sheltered northeast persona. I’d never carried a fully loaded overnight pack, crammed my foot into a climbing shoe, or ridden a bike in a place where suspension mattered. Within this dazzling array of backcountry sports, nothing piqued my interest quite like climbing. Or, rock climbing as I called it when I proudly announced my newest hobby to my gaggle of coffee shop coworkers.

With this lack of experience came a lack of inhibitions. I’ve always been the type of person to dive headfirst into a new activity. It’s a combination of a desire to prove myself, a lower-than-average risk perception, and a heaping dose of overconfidence. By the time I decided to try “rock climbing,” I had already tackled my first overnight backpacking trip with minimal research and minimal resulting issues. I had tried mountain biking and found I could walk a section when the terrain seemed above my paygrade. To me, climbing was simply the next step.

But there was a difference in learning to climb compared to my first attempts at backpacking and mountain biking. Falls weren’t from bike height, and I couldn’t stab a trekking pole into the ground or put a foot down to save myself. Taking a high-consequence fall was more likely than I could comprehend. The technical skills weren’t just to aid efficiency: the knots, belay strategy, rappelling technique, and rope management could be the difference between a moderate whip and a ground fall.

None of this registered as I flailed on the rainbow plastic holds and felt sparks of joy as my muscles moved in a flow I’d never before experienced. I relished the soreness in my forearms, the feeling of increasing strength, the pride that accompanied tackling higher-rated routes.

I climbed in the gym every day for a month, mostly alone, but occasionally top-roping with other solo climbers. I was friendly and ready to meet people but didn’t have a climbing community.

On one of these afternoons in late summer, I sat sifting my hands in the chalk bag, scanning the beginner problems scattered across the wall. A heavily muscled guy around my age strolled in, shoulder-length hair, a cut-off t-shirt, and the type of swagger that immediately draws you in. Following him were two other guys around the same age. They had guest passes, but their shoes were soft and worn, their chalk bags dusty from use. I immediately walked over and introduced myself.

They were coworkers from Yellowstone National Park, spending their summer working hospitality jobs with the goal of escaping work on their days off to climb in Montana and Wyoming. Bozeman was their base camp for a trip to Wyoming to climb single-pitch sport routes around the Tetons. Within an hour of chatting and bouldering, I somehow portrayed enough confidence to warrant an invitation on the trip.

I dashed out of the gym and across town to REI, clutching a sticky note scrawled with quick draws (12), ATC, slings. I swiped my credit card, gathered my armful of new swag, and met the group of guys back at my apartment, where we assembled climbing gear and camping items for the next three days.

The things I didn’t know on this trip so vastly outnumbered the things I did know that it’s almost hard to remember them. I want to deny that I cleaned a route 40 feet in the air while someone yelled instructions from the ground. Or that I asked them how to clip as I was well past the second draw on my first lead. Or that I belayed a man who outweighed me by 50 pounds while standing ten feet away from the wall. I smashed face-first into the granite when he fell.

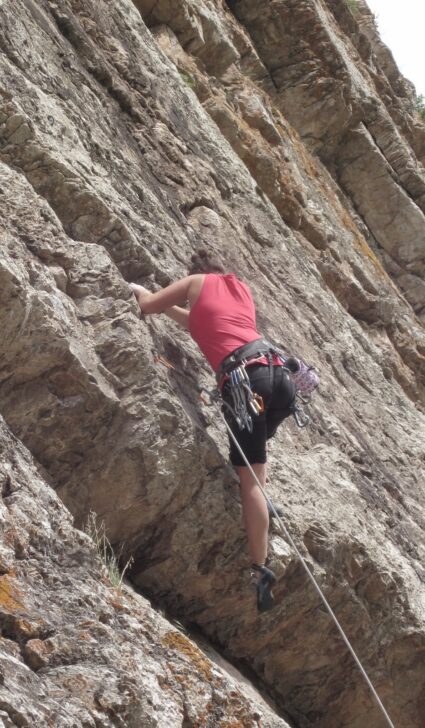

I told myself that I couldn’t show hesitation or tell them no, because I would never be invited back. I gritted my teeth and fought through any potentially overwhelming nerves. Focus on the rock, pull the rope up, clip it into the draw. Move your feet. Move your hands. Worry about the top when you get there. I carefully maneuvered up the blocky 5.9, reveling in the thrill of my first lead. They shouted instructions at the top, and I clipped the anchors, flushed with pride.

I lead routes, belayed, and cleaned anchors without ever having practiced, and without any understanding of technique and consequences. The way they explained it made sense: I was top-roping their climbs, so of course, I was going to clean them. Everyone has to do their part. I gamely agreed, even though it makes me cringe to know that I didn’t understand anchors, rappelling, prusiks, going indirect. My understanding of the consequences of tying in incorrectly, or dropping the ATC or my end of the rope was none. I was so thrilled to be outside climbing with this group of handsome men, indoctrinated into their group and beaming as they praised my level head and bravery, that it surpassed every alarm bell I should have been heeding.

The thing about this egregious display of bad judgement is that there were no accidents. Nothing bad really happened. I wound up bruised and somewhat unnerved, but I didn’t know enough to be scared and certainly not enough to understand the consequences of what I was doing.

Because there were no consequences, I didn’t learn any immediate lessons—not for years. I returned from the trip feeling successful. Like I’d cut the switchbacks of the learning curve and accelerated an entire season. To me, I’d gone from a person who had been flopping around a gym for a few weeks to an outdoor lead climber in just one weekend. I didn’t understand how close to catastrophe I’d been. If I’d tied the wrong end at the top of a route, or fallen on a backwards clip, or dropped the rope as my climber fell, the consequences could have been severe, tragic.

Climbing did become a core part of my social life, athletic outlet, and backcountry identity. After that trip, I slowly relearned outdoor climbing skills and wound up with an incredible, badass community of climbers. Safety and protocol were paramount in our endeavors while preparing for a trip, at the crag, and during all downtime. We knew to communicate with each other and how to verbalize if something unnerved us. It was such a far cry from the way I learned that it took literal years to look back on my first experiences climbing outside and understand there had been something wrong. My desire to be included and to prove my own worth swept easily over what I inherently understood to be unsafe, and it was too easy for me to ignore it.

I can say it was mostly dumb luck that let me get away with leading routes, lead belaying, and cleaning anchors with no understanding of how to do it. Looking back, years later, it still sends a shiver through me and a quick thanks to the backcountry recreation gods that somehow, all the correct pieces fell into place. It would have been easy not to have been so lucky.

There’s no shame in not knowing what the hell is going on, and there’s no wrong time to stand up and let your group know you’re in over your head. Whether you’re just mapping out the plan for a backpacking trip across technical terrain, loading the climbing gear into the car, or already deep in the backcountry, when you feel uncomfortable, speak up. If the people you’re recreating with are worth your time, they won’t judge. The people I went climbing with were good-natured, goofy, and out to have a good time. I can pretty much guarantee they would have been totally fine if I’d said I wasn’t comfortable with leading, lead belaying, or cleaning routes, but that’s neither here nor there. As the person who now takes new people out, I’m on the other end of the rope, and the first thing we do is make sure the new person feels comfortable and confident in their skills and the task at hand. It’s the best kind of communication to pass down the line.

The Learning Curve is a monthly column by outdoor journalist Maggie Slepian which will examine human-powered outdoor adventure through the lens of beginners. How do beginners learn our sports? What pitfalls do they face? How does mentality shift through time? And how should experts treat beginners? The Learning Curve will cover all this, and more. Got suggestions? Drop Maggie a line in the comments.

Related Content

- Andrew talks about how to treat newcomers in his essay Beginner’s Mind: A Lifelong Ground Sleeper Takes to the Trees.

DISCLOSURE (Updated April 9, 2024)

- Product mentions in this article are made by the author with no compensation in return. In addition, Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for product mentions or placements in editorial coverage.

- Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be affiliate links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light's gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you'd really like to support our work, don't buy gear you don't need - support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead.

- Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear.

Home › Forums › Learning Curve: In Over Your Head