Topic

So I have a new Tent plan for 2021…input welcome

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Home › Forums › Gear Forums › Gear (General) › So I have a new Tent plan for 2021…input welcome

- This topic has 176 replies, 35 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 2 months ago by

Roger Caffin.

Roger Caffin.

-

AuthorPosts

-

Dec 13, 2020 at 7:59 pm #3688836

After a bit of mathematical self-tutoring, I can halfway follow some of the diagrams, now…and I think that the most accurate statement so far is this:

Maybe an interesting problem for a grad student.

As best I can tell, the forces involved in this kind of modeling are extremely complex; fabric movement, wind direction and velocity and the resulting pressures that are created, stretch and elongation in the ropes, adjacent panel shape and geometry…it all gets so damned complicated that simplification of the forces involved becomes as misleading as it is enlightening. With that in mind, I’m going to get more serious about making adequate sacrifices to the gods of good campsites, and I’m going to yet again wish that the vestibules on trekking-pole-supported shelters like the ones in question could be just a tiny bit bigger.

And I’m going to invest in some additional cordage and stakes, too.

Dec 13, 2020 at 8:05 pm #3688839Wow. Cool discussion.

here’s some conjecture; no math. Go easy on me lol

it may be helpful in explaining the perceived differences to measure overall movement at the tent stake head. simple, I know but hear me out.

I notice the model above assumes static ground fixed point / which is unrealistic in high winds).

If I understand correctly, stakes work based on surface area holding power (assumption 1). When They wiggle that surface area contact is reduced and holding power as well (assumption 2). So a measurement of movement over time at the tent stake head that compares wiggle or “movement” with and without struts would help investigate a difference that may impact the stability. I think this is relevant. adding a fulcrum between two points like the ground and the tent (strut) not only change forces but I imagine there is less movement translated to the stake compared to a strut less design (assumption 3).

If this is correct then a doubling or tripling of the struts from the same ground point out toward the stake in a lock pitch design would potentially add more perceived stability then other mechanisms by further reducing transferred movement to the stake. Perhaps in this way the strut has a hidden agenda in structural benefit (assumptions 4,5,6).

Dec 13, 2020 at 8:08 pm #3688840Pity the poor grad student!

Adequate sacrifices – always wise.

some additional cordage and stakes How awfully . . . pragmatic.

I always try to have one left-over tent peg in the bag, and I always have a few grams (= many metres!) of Spectra string.Movement of the head of the stake My stakes do not move after I have put them in fully. ANY movement means that the soil/plant structure around the stake has collapsed. That means the stake is coming very close to coming out.

Cheers

Dec 13, 2020 at 8:22 pm #3688843“I have seen yachts sailing (tacking) INTO the wind. I suspect the model presented here is not entirely correct.”

That’s because there are additional sails adding other forces and/or other components (e.g. keels) re-direct this orange force. The orange force is fully correct in describing the force that the wind adds to that one sail – sail boats just do other things as well. Imagine a sail boat with only a main sail and no rudder or keel – just a floating tub. It’s not going to be tacking into the wind.____________________________

Anyways, I should really step out of this thread since I’ve already spent way too much time on it. I think I’ve adequately demonstrated my two main points, and gotten some agreement on them, which are:

1) Wind on the tent results in a force on the strut that is in line with the fabric.

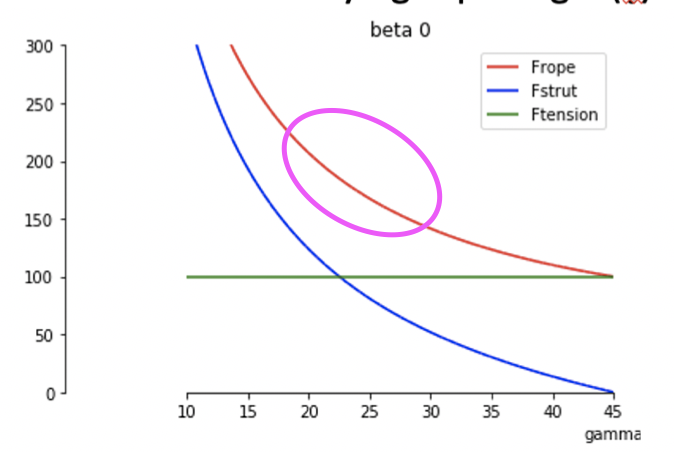

2) When that happens, struts will create a mechanical advantage (added tension) on the stake unless the stake is quite far out (the cord to the stake is no steeper than the tent panel). If the cord to the stake is steeper then the tent panel, then struts increase tension on the stake. For example, a vertical strut and a steep cord (e.g. only 20-30 degrees from vertical) will multiply the wind force to 150 – 200%, as shown in the pink area here:

While added tension on the stakes tends to be a negative with struts, I whole heartedly agree there are many positives. At the campsite, all that matters is keeping those stakes in the ground. Added tension from struts can be easily mitigated with better stakes or longer lines. I’m not opposed to struts and you may see them on one of my designs some day.

Dec 13, 2020 at 9:14 pm #3688855Good fun, tx for all the inputs, still much to learn, personally. Looking forward to your new designs, Dan & all the other outstanding designers out there.

Dec 13, 2020 at 9:29 pm #3688860This has been one of my favorite all-time threads at BPL. I have my load sensors and a Notch with Sil and DCF canopies ready to go! Just waiting for the big wyoming winds now.

Did snow-load tests this week, still need to work thru the data, but first impression is that the struts have a strong positive impact on snow loading…as expected based on Alexandre’s model. When I pitched the Notch w/o struts, stakes ripped out. W/struts: nope.

Dec 13, 2020 at 9:39 pm #3688863Also, I’ll add. And this goes in line with Roger’s note about wind speed vs. height above the ground.

When we’ve done load sensor analysis on guylines, some observations:

- Wind speeds are turbulent – more dynamic at ground level; they are more laminar the higher up you go.

- Dynamic loads create very high impact forces on tent stakes. We’ve noted this previously.

- Winds are *not* unidirectional, especially w.r.t. turbulence at ground level. We’ve measured vertical winds, horizontal winds, and everything in between.

This is a complex problem to model. Don’t be suckered into simplistic mathematical solutions, which mainly model static loading and linear force vectors.

Tent stakes rip because of the cumulative dynamics of massive forces exerting pressure on tent stakes, a little bit at a time, over many time periods.

This is why struts and rocks work – they have the ability to dampen millisecond-resolution force vectors…

Dec 13, 2020 at 9:50 pm #3688866Winds are *not* unidirectional, especially w.r.t. turbulence

And how!

I camped behind a very big rock once, ‘for shelter’. The tent was hit by wind from 5 directions in fast succession: all 4 sides and downwards too.These days I prefer to camp just downwind of a clump of snow gums. If there are any.

Sometimes there aren’t any.Cheers

Dec 14, 2020 at 1:54 am #3688885This is way out in left field, but with all the math and engineering being thrown out, or maybe I missed it; reading through all this and looking at the “data,” I see nothing about the Bernoulli effect. We have a bunch of info on the force on the strut and fabric with assumptions about that, but I don’t see the wind force going across the fabric is added as maybe a negative to the load forces (minor as it might be). All assumptions I have seen so far are on a single load force of one direction, i.e. Dan’s sail diagram and static line guy, and in the load calc’s from a few pages ago. If you are going to get really technical about this, someone has to add uplift to the equation. Who knows if we were able to get Roger’s real-world testing, this might be the canceling effect on Dan’s 2:1 pulley (2:1 is a bit of a stretch I think).

Of course, it is really late and I am brain dead from all this reading. YMMV.Dec 14, 2020 at 2:05 am #3688886At least one if not two PhDs.

Dec 14, 2020 at 6:13 am #3688892This is a complex problem to model. Don’t be suckered into simplistic mathematical solutions, which mainly model static loading and linear force vectors.

@ryan – Same conclusion I came to. I spent a day or so over this past weekend learning enough of the math – literally sat down with a few high-school textbooks and some online tutorials – and came away realizing that there’s so much in play here that it can’t be hashed out in a forum thread. Because of that complexity it’s easily possible that all of the conflicting theories that have been mentioned herein are all essentially correct; without a cohesive model, we’re all somewhat in the dark and only capable of describing a small portion of what we see.And yes…what a fascinating discussion this has been!

Dec 14, 2020 at 11:13 am #3688952Most definitely very interesting stuff and I’m looking forward to Ryan’s results! Just be safe out there Ryan we know how the last high wind excursion went with the HMG Tent. Hopefully the TT Notch fairs a lot better but those were some crazy wind gust last time! To be honest I had no idea my post would lead to an awesome discussion of this magnitude. I was expecting some input but not 7 pages deep on the workings of tent geometry and physics equations. You guys are awesome!

Dec 14, 2020 at 11:30 am #3688956Just be safe out there Ryan we know how the last high wind excursion went with the HMG Tent.

I wasn’t here for that. What, exactly, happened..?

Dec 14, 2020 at 12:23 pm #3688967I wasn’t here for that. What, exactly, happened..?

Her’s the link. You can watch it all or skip to about the 22:00 min. mark. Pretty much down hill from there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gl98SOoKq38

Dec 14, 2020 at 1:30 pm #3688981That is an uncomfortably familiar situation.

I once had a storm come up late one afternoon in the Virginia highlands, and things got rough even though we were only at 5,300 ft. Kind of a snap blizzard and cold front all at once; the expected low that night was right around freezing so I took a 20° bag, but by midnight the temps were down in single digits so we were burrowed in and trying to sleep. I had a lighter tent that wasn’t up to the conditions, but luckily we were able to get it anchored near a copse of older, heavy trees that could break some of the wind, using deadmen made from stuff sacks that we dug into about 18″ of snow. One line was snaked around a tree trunk; we lost that one around 1:00 in the morning when the wind was high enough to start really moving things around, and something sharp on the tree severed it. Instant loss of stability; the tent was all over the place just from one anchor failing. I had to climb out and re-secure it to a different point with an extra piece of cord; that wasn’t fun. I think we might have gotten ten minutes of sleep that night. We were up and going as soon as the weather died down at dawn, and we promptly got the hell out of there while we had a weather window. I guess it goes to show just how quickly things change in the hills.

Naturally, if my tent had strut corners, it would have easily survived and the entire area would have been thirty degrees warmer.

Dec 14, 2020 at 4:23 pm #3689013An interesting thing that I just saw on YouTube while watching wind tunnel tests of various tents is the impact of panel deflection on tent failure: once a fabric panel starts turning into an inwardly-cupped, spinnaker-like shape from wind pressure, the stresses seem to start radically rising. Once it is bowed far enough, failure becomes imminent; after a certain point the pressure on the entire structure seems to go WAY up and – by way of example – a tent that was fine at 25 mph and stressed at 28 mph gets squashed at 30. A comment from the narrator on one video on the TentLab channel sums it up nicely: “When you watch enough of these [tests] it kind of dawns on you that that cupping is really what’s loading the tent so much, as it changes the aerodynamics and catches wind…so anything that causes more cupping – like, stretchy fabric or stretchy guylines or anything like that, actually makes the tent weaker.”

Here’s the video from which I drew the quote.

It seems that panel size really does have a massive effect on the ability of wind to catch and impart pressure to the tent structure…and if I start thinking about it like how the aforementioned spinnaker works, this makes complete sense. And that’s the first time in this thread that anything has made complete sense to me! Yay!

Dec 14, 2020 at 6:07 pm #3689037“so anything that causes more cupping – like, stretchy fabric or stretchy guylines or anything like that, actually makes the tent weaker.”

That poses the question: since silnylon is stretchier that DCF, presumably it will “cup” more. Does that mean it might fail more quickly than the DCF equivalent?

Moreover, having used Bibler tents on & off for many years, I’ve often wondered about how the fabric material itself contributes to overall tent stability. Anyone that’s been in a fully guyed out “Todd Tex” tent probably feels a wee bit more secure than a tent with the same pole arrangement but built with a thinner fabric. Anyone compare a traditional Bibler I-tent with the BD FirstLight before?

Dec 14, 2020 at 6:50 pm #3689043That poses the question: since silnylon is stretchier that DCF, presumably it will “cup” more. Does that mean it might fail more quickly than the DCF equivalent?

I think that’s a factor of fabric strength as much as geometry and other support. It’s just an interesting observation on the part of the narrator that correlates well with another observation on my part: namely, that when a sail really snaps taught, that’s when it really starts to pull. Sure, there’s motive force being generated even when it’s badly trimmed, but when it gets into the correct position it starts to seriously move things. Same effect here…and the same kind of complexity, if not moreso.

Dec 14, 2020 at 7:52 pm #3689058I’ve owned both the original single wall TT Moment and now the Moment DW and have often had to place rocks on the main stakes at each end. IF Henry Shires made the end cords longer then, as illustrated above, there would be less angle from the tent and thus less force on the stakes. No? In fact I may retrofit my Moment DW and Notch Li end cords for that reason.

I now have the long, twisted MSR Ground Hog stakes for those ends. Maybe with lengthened end cords I can return to the original MSR Ground Hog stakes.

Dec 14, 2020 at 8:39 pm #3689066I understand the observation about cupping of the fabric, but I do not think that having a stretchier fabric will make things worse.

I suggest instead that as the so-called cupping increases, the forces on the poles are also increasing, and that eventually those long thin poles cannot sustain the load, so they deflect and collapse. Granted, in some cases the increased cupping may permit more sideways deflection, leading to the collapse.

In other words, the cupping is just a sign of increasing load due to the wind, and the collapse is a fundamental design problem. Tent with long poles, big fabric spans and minimal guys simply cannot handle high winds.

Cheers

Dec 14, 2020 at 9:32 pm #3689073Fundamental design problem, or fundamental design inevitability? Seems like nothing is collapse-proof, except for things that have already fully collapsed.

Agreed on the cupping effect being a sign of increasing wind load; that’s what I was trying to say, but you used less words.

Dec 14, 2020 at 9:57 pm #3689077Have you read

https://backpackinglight.com/when_things_go_wrong/ ?

Tunnel tent taking 100 kph winds. I had to crawl to put the tent up in the evening and crawl to take it down in the morning.

Later on we had to abandon part of the escape route because my wife could not stand up in the wind.

But the tent was fine.Cheers

Dec 15, 2020 at 6:04 am #3689092All this talk about wind reminds me of the fascinating read on the DAC Wind Lab.

What seems most inserting (and relevant to this thread) is two things:

1) The discussion in the video about adding “Jakes corners” to the Sierra Designs Hercules, which allowed it to sustain 100mph winds. They kind of remind me a little of the “struts” that we are all discussing. (I think I remember when SD came out with this while I was working at REI. At the time, it seemed like just another “thing” to add weight to the tent and get accidentally stepped on by an inexperienced user. I never saw the video back then.)

2) Just how powerful uplift forces become at higher speeds, which helped contribute to the design of the TNF Spectrum 23.

Another thing which I think about often is how much altitude and relative humidity might mess with things. A 50mph wind at 10,000 feet in elevation is NOT as powerful as 50mph wind at sea level. But just how much that plays into things, I really don’t know.

Dec 15, 2020 at 6:45 am #3689095Have you read

https://backpackinglight.com/when_things_go_wrong/ ?I have, now. Never seen anything that bad, although I came close one time; I’ve invested more wisely in gear since then, and gotten better at saying “Nope…not today.”

Dec 15, 2020 at 10:00 am #3689141Speaking of cupping, I sometimes wonder whether caternary-cut ridgelines are a net positive with respect to wind resistance. If we consider a four-sided pyramid tent, caternary cuts could be seen as ‘pre-cupping” the panels, in comparison to flat panels and straight ridgelines.

I think caternary cut ridgelines are generally seen as positives – they help get taut ridgelines and panel, as well as shrink the cross-section of the tent a little, which should both help with wind-resistance. But if we had two tents with substantially similar cross-sections and identically taut ridgelines and panels, would the caternary-cut tent perform better or worse in the wind than the flat-panel tent? (Imagining two pyramid tents here)

Roger, I would think that stretchy panels, if they allow increased cupping, would be a net negative. If you could make a tunnel tent identical to one of your silnylon ones, but could make it with some kind of skin that did not deflect at all, and we assume that your pegs are adequate, wouldn’t this tent be able to sustain greater windspeeds than your silnylon one by virtue of maintaining more aerodynamic shape as the wind becomes more and more extreme?

I know Ryan is testing a bunch of wind and tent-related things; one comparison that really interests me is DCF Khufu vs. silnylon Khufu. Ryan has written that its sewing and cutting precision makes his DCF Khufu the most wind-resistant of his DCF shelters, as this precision allows for a very taut pitch. (Conversely, he prefers the silnylon versions of other trekking pole shelters (with more complex geometries) because they pitch more tautly.) If the DCF and silnylon versions of the Khufu pitch with roughly equivalent tautness, this would seem to be a great comparison to evaluate the effects of panel deflection and “cupping” on wind-related variables like force at the stakes, deflection of panels into living space, wind hammer, flapping (noise inside the tent), stress on the center pole, etc.

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.

Forum Posting

A Membership is required to post in the forums. Login or become a member to post in the member forums!

Trail Days Online! 2025 is this week:

Thursday, February 27 through Saturday, March 1 - Registration is Free.

Our Community Posts are Moderated

Backpacking Light community posts are moderated and here to foster helpful and positive discussions about lightweight backpacking. Please be mindful of our values and boundaries and review our Community Guidelines prior to posting.

Get the Newsletter

Gear Research & Discovery Tools

- Browse our curated Gear Shop

- See the latest Gear Deals and Sales

- Our Recommendations

- Search for Gear on Sale with the Gear Finder

- Used Gear Swap

- Member Gear Reviews and BPL Gear Review Articles

- Browse by Gear Type or Brand.