Preface

I’ve worked professionally in the outdoor industry for 35 years as a guide, educator, gear maker, and publisher. I have developed and managed various outdoor business ventures, including gear and apparel design, e-commerce, print and digital publishing, outfitting, institutional education, research (public- and private-funded), and business development (agency) consulting.

My background in research and engineering (and my passion for understanding how things work) motivates me to analyze and question industry practices so consumers can make more informed decisions about how and where to spend their money, time, and energy.

Having worked in digital publishing for the past 25 years, I’ve watched our industry grow from its digital marketing infancy to where it is today – some will say “maturity”. I’m not sure we’re there quite yet. Much of the time, it seems like unleashed puberty on a spring break vacation.

It’s from this context – my career as an outdoor industry professional and digital publisher – that I write today’s letter. My sincere hope is that this discussion will identify salient trends about how outdoor gear is made, marketed, and sold, so you can be a more informed consumer.

Ryan Jordan •

Owner/Founder, Backpacking Light

Estes Park, Colorado – April 9, 2024

Introducing the Outdoor Recreation Industrial Complex

Industrial complexes arise in response to favorable socioeconomic climates that provide business profit opportunities. In the case of the outdoor recreation industry, the past 50 years have seen the emergence of such a climate, connected by:

- our natural (outdoor) world;

- increasingly complicated politics and policy of land management, conservation and the environment;

- the increase in outdoor participation, fueled by our recognition of outdoor recreation for health, well-being, and adventure – and by marketing that communicates the aspirational qualities of outdoor adventure;

- advances in materials and technologies that make outdoor gear lighter, more comfortable, more stylish, and more performant;

- the expansion of corporate-owned big box retailers bringing goods to the masses; and

- the internet as a means of facilitating more rapid commerce, communication, consumer profiling, and digital marketing.

The outdoor recreation economy includes the products and services sold to both outdoor businesses and outdoor consumers. Dominated by apparel, footwear, equipment, and accessories, outdoor gear sold through retail channels in the U.S. generates $25-$30 billion a year. Although outdoor retail has seen its ups and downs through the years, especially in the face of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, its long-term growth is positive. The reason for this is a simple and time-tested axiom of market growth: big brands are scaling their revenues into new markets and selling more stuff to the same customers.

Outdoor gear brands depend on increased consumption for their growth, but this is at odds with the type of sufficiency-oriented consumption that ensures the long-term sustainability and health of our industry and our raw material resources. Consumers feel this pain more acutely as individuals than outdoor industry businesses do. Outdoor users (a.k.a. gear buyers) feel the sting in terms of the time and energy spent shopping for outdoor gear, paying for it, storing it, deciding which gear to take on a trip, cleaning it, repairing it, and at the end of its life, disposing of or reselling it.

Much of this pain comes from purchasing gear in response to marketing claims and messages that owning some new piece of gear can address unmet performance or aspirational expectations.

Thus, you may find yourself tired of wasting money on outdoor gear, in an endless cycle of buy-and-return, or otherwise accumulating gear that you seldom use or that doesn’t meet your needs.

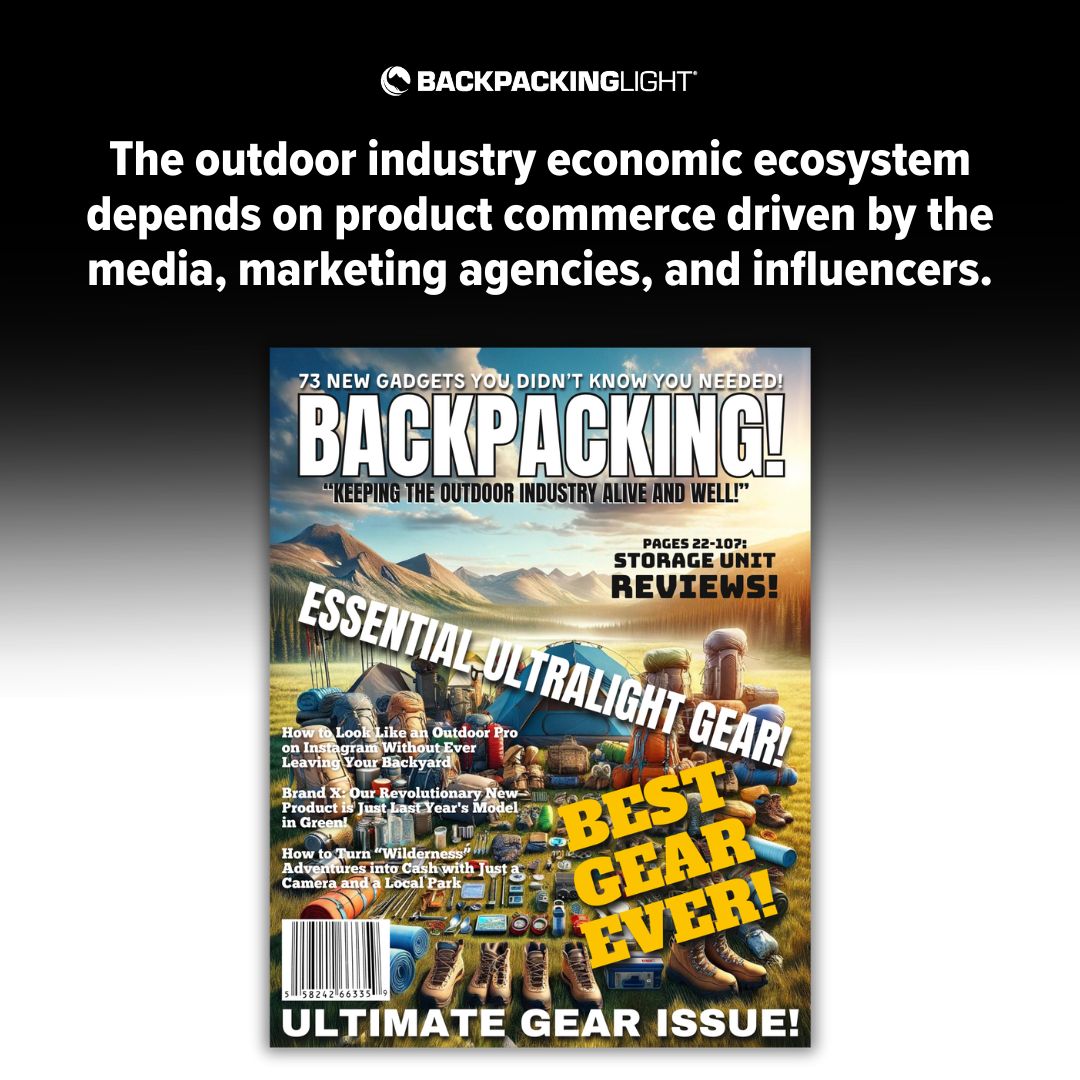

If so, it’s not entirely your fault—the nearly $900 billion [1] U.S. outdoor recreation industry (including its industry associations, brands, suppliers, public relations agencies, magazines, websites, and influencers) depends on you buying the same types of gear over and over again as part of its financial sustainability model. They spend billions of dollars a year on marketing tactics that promote new new gear as the latest unicorn that will solve your gear problems.

Let’s explore some of the outdoor industry’s inner workings, get back on track, and put the power back into the hands of the consumer—those of us who want to spend more time outdoors and take advantage of its health and wellness benefits (which, incidentally, do not include the accumulation of unnecessary gear).

So strap in and get ready for a ride toward becoming a more informed consumer …

… and welcome to Backpacking Light.

Outdoor industry growth, consumer chaos, and the truth about how outdoor gear is made, marketed, and sold.

Consumer chaos is rooted in information overwhelm. We are faced with dozens (or more) options for gear that are so similar to each other that it’s difficult to understand how designs are differentiated and how those differences impact product performance. This is compounded by marketing messaging that’s not accurate, overly exagerrated, or otherwise untrustworthy.

Three dominant themes drive consumer chaos in the outdoor industry:

- Outdoor industry growth, driven by revenue scaling objectives of big brands;

- Product market expansion and saturation;

- Confusion about products in new global distribution channels;

- Influencer marketing.

TL;DR:

- In order for the outdoor industry and its largest brands to grow, they must sell cheaper, less performant products to as many people as possible.

- Brand scale is achieved by maximizing “customer lifetime value,” [2] which depends on you buying as many tents, packs, bags, pads, stoves, layers, and gadgets as possible – including duplicates of all these items in the name of “upgrades” and “improvements.”

- Brands with the biggest marketing budgets win, because they can spend more money to grab your attention.

- Brands hire (pay) affiliates, ambassadors, and influencers (collectively referred to hereinafter as influencers) to act as de facto members of their sales force to help sell their gear. The marketing playbooks used to promote influencer media channels (e.g., blogs, social media, and YouTube) are grounded in the attention economy: feed algorithm manipulation through headline and image clickbait, search engine optimization formulas, and short-form content.

- In today’s revenue-scaling culture, brands prioritize influential personalities over experienced experts because influence sells more.

1. Outdoor industry growth & big brand scaling

The outdoor industry is a nearly $900 billion powerhouse in the United States economy, and it’s growing more than 2.5 times faster than the overall economy [3]. With economic power comes political power (and vice-versa), so the motivation for expanding the outdoor recreation economy among its largest brands and industry associations is very high.

This growth is achieved primarily through scale. Scale is achieved primarily by distributing existing products into new markets, not by creating new and innovative products for existing markets. Pursuing scale means companies are shifting dollars away from R&D and into marketing and PR. As marketing efforts intensify, and product lines achieve scale, competition for consumers becomes fierce, and marketing messages (and product performance claims) become more persuasive and manipulative.

In a presentation at the Outdoor Retailer Winter 2023, an industry analyst wasn’t shy about disclosing this truth: “Most new products haven’t provided customers with innovative features … creative marketing will be essential to driving sales in the future.” [4]

2. Product market saturation vs. research, development, and innovation

The thirst for revenue scaling results in product markets becoming saturated with commodity goods (i.e., there is little product differentiation). In this environment, brands with the biggest marketing budgets win, because they can spend more money to grab your attention.

Two things happen here:

First, the product “features” that are marketed all solve the same problems for consumers, so the brands that sell the most products are the ones that yell the loudest about them to the customers who know the least. Backpacking Light exists to educate consumers so they are equipped to distinguish innovation from commodity marketing.

Second, brands allocate money away from innovative product development and toward marketing existing (less innovative) products that are easier to market to larger, less educated audiences.

Educating consumers about products that are innovative is far more expensive than just spending money telling consumers that the products are innovative. Did you get that? Read this paragraph again until it sinks in.

Bottom line? Big brands get richer, outdoor consumers get poorer, and we all keep buying the same old crap, hoping it turns out differently.

3. Confusion about products in new global distribution channels

Products that are sold primarily through discount retailers, resellers, online retail marketplaces, and white-label products contribute to market chaos. The inconsistency in product availability, product specifications, brand and model naming, and unethical white labeling and distribution practices create confusion for customers. This type of product distribution dilutes the value that small businesses, startups, cottage brands, outdoor specialty brands, and outdoor specialty retailers provide to the market.

Backpacking Light does not promote or link to, engage in paid advertising or affiliate marketing with, or otherwise partner with discount retailers, resellers, online retail marketplaces, or brands distributing primarily through these channels or distributing primarily white-label products.

4. Shifting brand marketing priorities: from expertise to affiliate and influencer marketing

In the old days, outdoor industry gear brands engaged in reputation marketing.

Reputation marketing is based on the idea of supporting working guides, educators, wilderness first responders, and other working professionals.

After all, working professionals had the most extensive and legitimate expertise and experience and would make the fairest recommendations about how gear performs in the field.

When reputation marketing occurs, the types of brands that won were the brands that created the most performant products.

And the most performant products are what we’re all after, right?

Those days are slipping away.

Because reputation marketing is expensive and lacks wide reach into broad markets, so it isn’t really an important part of revenue scaling strategies.

We have now replaced reputation marketing with affiliate marketing, ambassador marketing, and influencer marketing.

Brands hire (pay) affiliates, ambassadors, and influencers (collectively referred to hereinafter as influencers) to act as de facto members of their sales force to help sell their gear. The marketing playbooks used to promote influencer media channels (e.g., blogs, social media, and YouTube) are grounded in the attention economy: feed algorithm manipulation through headline and image clickbait, search engine optimization formulas, and short-form content.

Influencers connect to and gain trust with their audience through authenticity:

“[The] ethics of authenticity is premised on two central tenets: being true to one’s self and brand and being true to one’s audience. This framework puts the influencers’ brand identity and relationship with their audience at the forefront while simultaneously allowing them to profit from content designed to benefit brands.” – Wellman et al., Journal of Media Ethics [5]

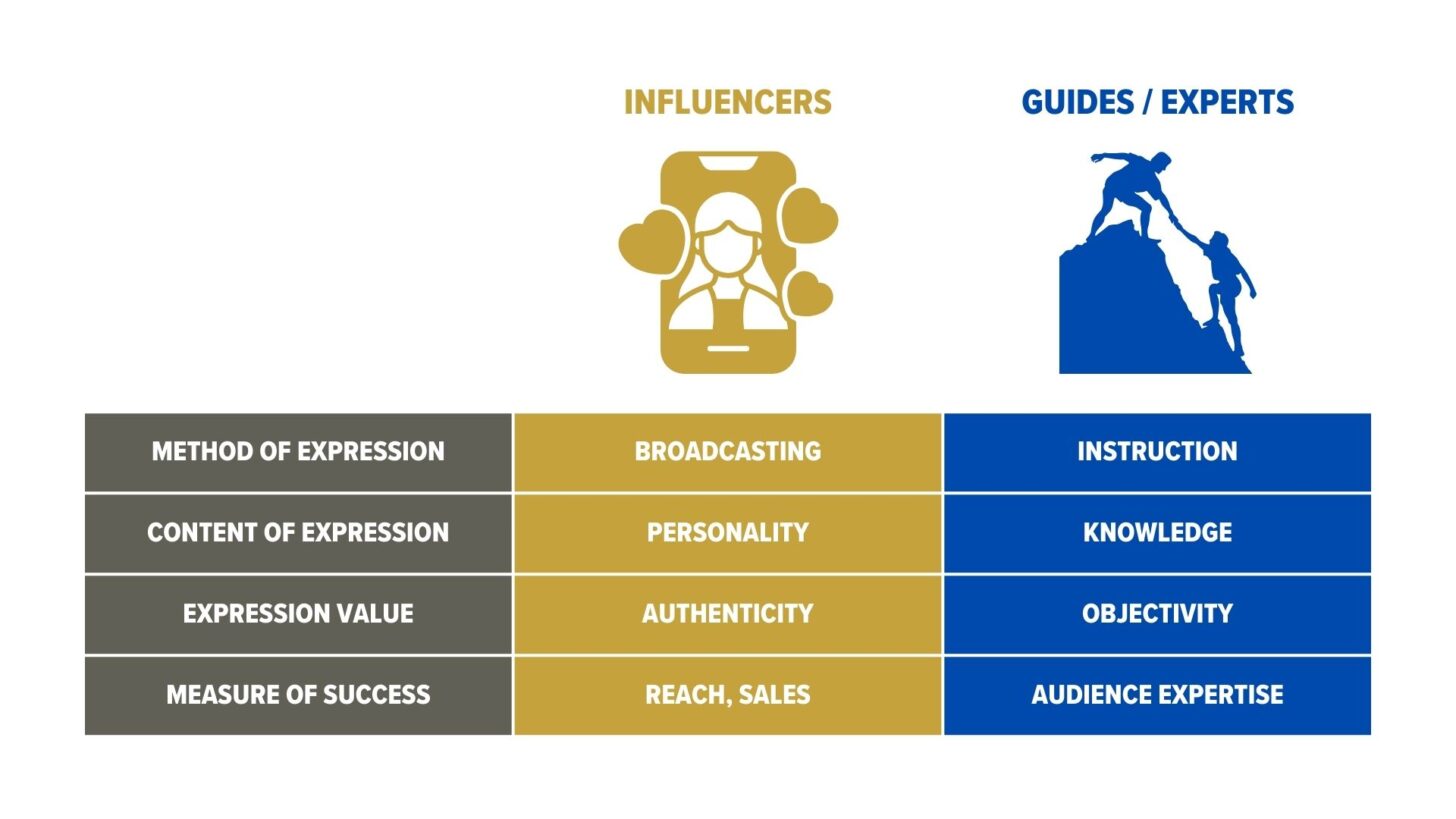

But authenticity and expertise are two very different things.

Authenticity is influencer-centric, a collection of personality- and behavior-based values centered around emotional transparency, unique expression of personality, engaging and creative presentation, and vulnerability. In addition, successful influencers share the traits most common with successful sales representatives – drive, resilience, passion, enthusiasm, confidence – and the willingness to acknowledge and follow marketing playbooks that generate sales.

Influencer audiences are earned primarily by distributing entertaining and engaging content. Entertainment and engagement are the two most important attributes of content that garners the most attention (algorithmic reach), the most views (viewer engagement), and the most clicks (which lead to affiliate commissions).

Experts, guides, and educators (and their expertise), on the other hand, operate on different sets of values. Their recommendations and guidance reflect research, testing, knowledge, critical thinking, acknowledgment and analysis of bias, analyzing various contexts and use cases, and exercising student (or customer) empathy. The outcome of these practices is less measurable for the expert (and their sponsors) but more directly realized by the audience: development of the audience members’ expertise.

That’s not to say that experts don’t express authenticity, creativity, or personality. Nor can it be assumed that influencers don’t possess some level of experience. The important take-home message here is that brands prioritize influential personalities over experienced experts in today’s revenue-scaling culture because influence sells more.

“…brands prioritize influential personalities over experienced experts in today’s revenue-scaling culture because influence sells more.”

Where does that leave us as outdoor gear consumers?

As a result of this evolving brand-centric (as opposed to consumer-centric) outdoor recreation gear ecosystem, we (the consumers) end up spending money on gear we don’t need or that doesn’t work for us.

This extends into the outdoor education and information markets as well, so in our effort to learn, we receive inadequate skills training that doesn’t allow us to stay safe and comfortable outdoors. In addition, we spend enormous amounts of time and energy trying to find trustworthy answers to questions about outdoor gear, techniques, trip planning, and more.

This is the underlying issue we attempt to address at Backpacking Light. We aim to provide access to curated and trusted expertise that saves time, money, and hassle so you can reduce your pack weight, hike and camp more comfortably, and figure out what gear works best for you.

Backpacking Light aims to provide access to curated and trusted expertise that saves time, money, and hassle so you can reduce your pack weight, hike and camp more comfortably, and figure out what gear works best for you.

Our information and education are created with journalistic integrity, transparency, and expertise, and are based on:

- extensive wilderness field expertise based on professional guiding, institutional education programs, and expedition experience;

- science and engineering expertise applied to the design and analysis of materials and products; and

- rigorous research expertise that is rooted in scientifically sound research and testing methodologies.

This provides the framework for questioning industry practices, testing others’ claims, and making recommendations about gear and best practices.

We believe a culture of data, objectivity, and transparency provides a foundation of trust, so you can achieve your outdoor adventure goals without having to deal with clickbait, bias, conflicts of interest, and hidden agendas.

How do we know if an influencer is subjected to commercial bias?

All of us who participate in the business of the outdoors are influencers who are subject to commercial bias on some level.

So the question is not necessarily whether an influencer is subject to commercial bias but to what extent commercial bias affects the influencer’s business practices.

The Unethical Business of Influence to Sell Consumer Products

Influencers can use a variety of unethical tactics to increase sales – false scarcity; misleading, exaggerated, or unsubstantiated claims; bait-and-switch (“clickbait”) title and headline copy to boost content reach; creating false drama; using fake reviews and testimonials to inform their analyses; exaggerated claims about their knowledge and experience; psychological manipulation; obfuscation of product limitations; lack of disclosure of their financial conflicts of interest; hyperbolic claims; and failure to adequately contextualize use cases, target markets, and competitive products.

The result of exercising unethical influence tactics is a lucrative business model for the influencer but creates negative outcomes for the consumer: the accumulation of gear and debt; inadequate, misleading, or dangerous knowledge; and wasted time, money, and energy.

Researchers have been sounding alarms about influencer marketing for years, but these are not popular conversations to have: brands are able to leverage influencer audiences to scale revenues at lower costs more effectively than any marketing strategy in the post-digital age. As a result, brands carefully coach their influencers, influencers are protective of their golden calf business models, and less-informed consumers fuel the toxic positivity influencer culture that elevates encouragement over objectivity, trust, and transparency. One Swiss research group challenges the idea that influencer marketing is inherently ethical, noting that it’s keenly disguised as “consumer manipulation” and treated by brands with the same data analytics approaches they use to evaluate their return on investment for other digital advertising initiatives [6]. In other words, influencer success depends directly on the influencer’s ability to generate sales for the brand.

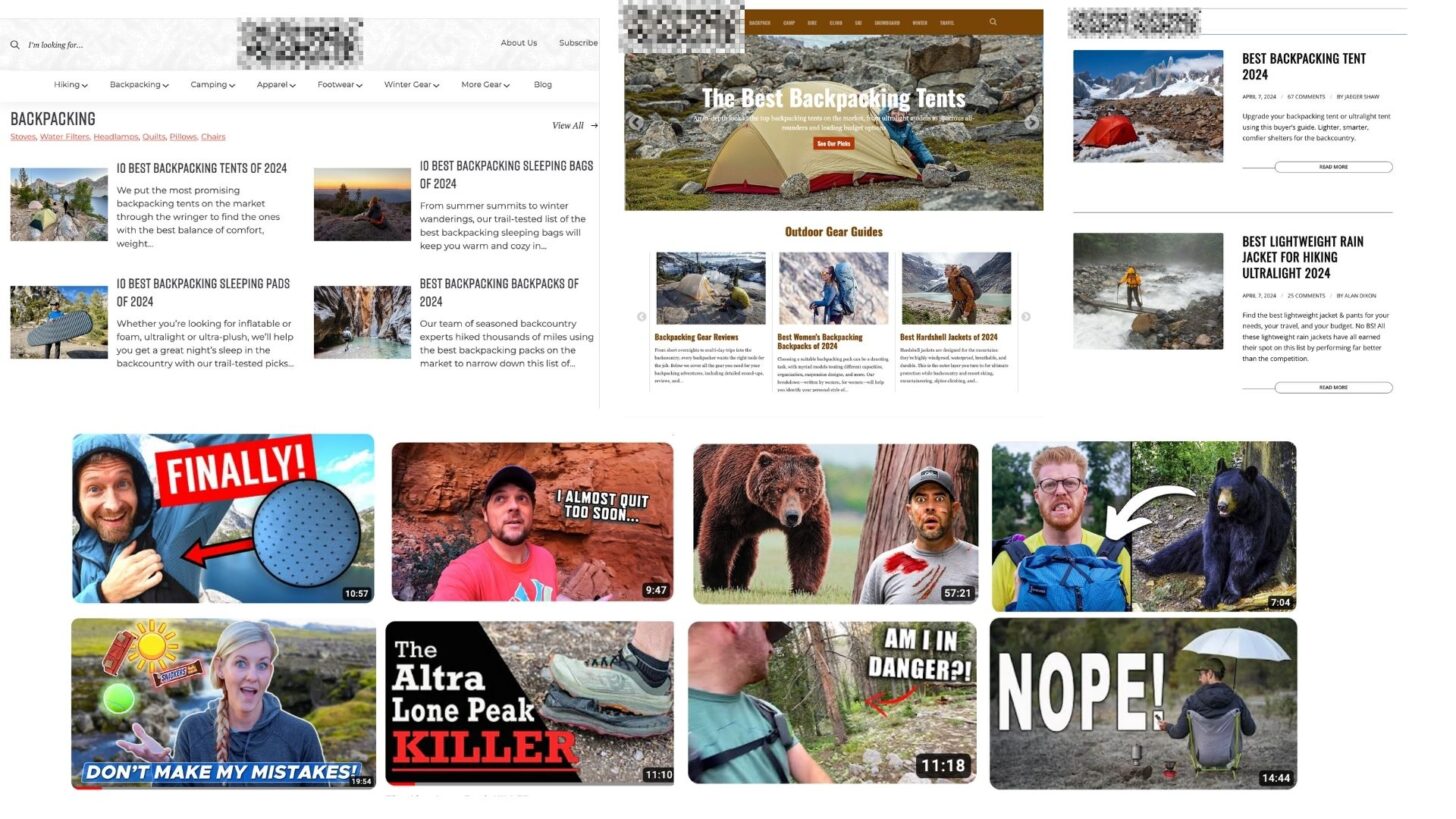

Of course, influence can be used as a force of good – to build connections to and inspire followers, publicize social and environmental issues, and educate people so they can enjoy the backcountry more. I will readily admit that I’ve watched – and have been entertained and inspired by each of the YouTubers shown in the image above. Some of them are funny, some of them are authentic, some of them I learn from, and some of them I follow regularly. All of them are good people who mean well and strive to make a difference in the world through their influence. This discussion and its context doesn’t take away any of that from them, or the value they bring to me.

In his keynote at SXSW 2024, Death of the Follower & the Future of Creativity on the Web, Jack Conte (Patreon founder) emphasized the risk involved with being an influencer on platforms that depend on algorithmic prioritization of reach and clicks (including SEO, social media platforms, and YouTube). The problem, he notes, is that algorithms are tuned for engagement, not value. In the never-ending battle for eyeballs, influencers are walking increasingly blurry ethical lines of consumer manipulation in order to scale their affiliate and paid partnership revenues. The formula is simple: engagement (reach→clicks) leads to product purchases.

Because influencers promote a generally positive culture, their followers often overlook financial conflicts of interest and blurry marketing ethics.

Influencers are financially accountable primarily to the brands they represent and not their followers, but they capitalize on the well-known mechanisms of follower-influencer attachment in order to sell products to them.

A recent study of social media influencer (SMI)-follower attachment via the lens of human brand theory [7] provided empirical evidence about how influencer personas “affected followers to perceive the SMIs as human brands who fulfill their needs for ideality, relatedness, and competence—all of which resulted in an intense attachment to SMIs. It was this positive emotion shaped with SMIs that transferred to SMIs’ endorsements and positively influenced the followers to acquire the products/brands that the SMIs recommended.” [8]

Financial accountability to the people you are selling products to is perhaps the most fundamental attribute of ethical transactions. E-commerce retailers and startup gear brands know this very well—if they don’t take care of their customers, their customers will return the goods and tell their friends. Since influencers are a step removed from the transaction, they aren’t directly responsible if the customer is unhappy with the gear the influencer recommends. With affiliate and paid sponsorship gear promotion, influencer accountability is diluted.

All of us participating in the business of the outdoors have some level of influence.

Although Backpacking Light does not fit the mold of a modern social media or YouTube influencer, we can’t deny that our voice and our recommendations have influence.

That’s a weighty responsibility that we take seriously. Influence and persuasion are powerful.

Understanding and studying the powerful psychology of influence and its ability to manipulate customers for revenue provides an essential foundation for developing and maintaining ethical business standards.

The rest of this letter discloses how we manage our own commercial bias in our efforts to bring trusted information to our followers.

Backpacking Light Membership as a Means of Accountability

Backpacking Light has multiple revenue streams, which help keep us sustainable in response to economic instability. Those revenue streams include the types of income that nearly all online publishers and influencers have with brands, including event and content sponsorships, advertising, and affiliate commissions.

However, Backpacking Light’s primary source of revenue are the membership fees paid by the hikers, backpackers, and other backcountry users who value and trust our expertise and education.

More than 70% of Backpacking Light’s revenue is earned through membership fees. Remaining sources of revenue include online courses, webinars, live event ticket sales, guided treks, consulting services, used gear sales, advertising, affiliate commissions, and event sponsorships.

If we break that trust or otherwise prioritize a gear brand’s agenda over advocacy for our members, our primary source of revenue will disappear – members will not renew their annual subscriptions.

This is the best possible type of accountability that cements our mission as a consumer advocacy organization first. Simply put, we work for (and derive most of our revenue from) our members, not gear brands.

If you are wondering if an influencer you are following has any financial conflicts of interest, evaluate them using the following litmus tests:

- Do they disclose their revenue streams? How much of their revenue comes from brands (e.g., affiliate commissions and paid partnerships) vs. their (consumer) audience (e.g., memberships, Patreon, contributions)?

- Do they acknowledge commercial bias beyond minimum FTC requirements? If so, do they disclose paid partnerships and affiliate commissions as influencing their recommendations and decision to insert product placements, or do they “deny or minimize bias”?

- Do they employ questionably ethical marketing techniques? (see “The Unethical Business of Influence to Sell Consumer Products” above). What accountability systems have they put in place to ensure that ethical practices are followed?

Backpacking Light Disclosure Statement

This letter, of course, is the long-form version of our FTC disclosure statements, which are routinely appended to the end of our articles and reviews. Here’s an example:

Product(s) discussed in this article may have been purchased by the author(s) from a retailer or direct from a manufacturer, or by Backpacking Light for the author. The purchase price may have been discounted as a result of our industry professional status with the seller. However, these discounts came with no obligation to provide media coverage or a product review. Backpacking Light does not accept compensation or donated/discounted products in exchange for guaranteed media placement or product review coverage.

Some (but not all) of the links in this review may be “affiliate” links. If you click on one of these links and visit one of our affiliate partners (usually a retailer site), and subsequently place an order with that retailer, we receive a commission on your entire order, which varies between 3% and 15% of the purchase price. Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of Backpacking Light’s gross revenue. More than 70% of our revenue comes from Membership Fees. So if you’d really like to support our work, don’t buy gear you don’t need- support our consumer advocacy work and become a Member instead.

Learn more about affiliate commissions, influencer marketing, and our consumer advocacy work by reading our article Stop wasting money on gear (this page).

What we’re changing about how we use affiliate links

Beginning April 20, 2024, we are changing how we use affiliate links, to create less confusion for our readers. Our primary goal is to avoid bait-and-switch tactics, so you know exactly where you are going when you click an affiliate link. We are in the process of documenting that strategy and will share it here with an update to this letter.

How we review outdoor gear

First, an important principle that is the foundation of our product review program:

Backpacking Light does not accept free or discounted products, money, or any in-kind service in exchange for product reviews. Advertising, sponsorship, and affiliate contracts will never be exchanged for editorial coverage, product placements or mentions, or product reviews.

For us, product reviews are research projects, not “content placements”. They are developed over the course of several weeks to several months. Product performance reviews and analyses are not only published as “gear reviews”, but are often discussed in our other information and education products as well, including our podcasts, webinars, and online courses. The review process includes (but isn’t necessarily limited to) the following components:

- Field testing that is appropriate to the type of product being reviewed.

- Side-by-side comparison between similar products in similar use contexts and environmental conditions.

- Bench-scale, laboratory, or other types of controlled testing environments.

- Interviews with users who have extensive experience with the product being reviewed.

- Consultation with subject-matter experts about materials, design, and engineering.

- Research about the product from other editorial sources, and evaluation of the sources in terms of their bias, reviewer experience, conflicts of interests, reputation, and review methodology.

- Research about customer experiences from published (and vetted) user reviews, and analysis of those user reviews for both positive and negative experiences with the product being reviewed.

In our reviews, we will disclose our review methodology and include in that disclosure the following as deemed necessary for justifying review claims: description of field testing, description of reviewer experience, and history of reviewer experience with related products.

When it comes to making product recommendations, we adhere to the following guidelines:

- We won’t recommend any product “for everyone”, because we understand that not all gear works for all hikers – we all have different needs, preferences, and styles.

- We won’t publish “Best ___ (backpacks, ultralight shelters, stoves, etc.) of 2024″ articles – these clickbait listicles are a sure sign that you are stumbling onto a website that is strongly biased by, and dependent upon, affiliate marketing revenues. Website publishers who engage in these tactics claim that these tactics are necessary to optimize search engine performance, because “that’s what people are searching for.” Well, there you go – by their admission – a great example of how clicks over community and affiliate marketing have hijacked our ability to find trustworthy product reviews.

- We’re OK with giving gear poor performance reviews. We generally don’t make it a habit to review lousy equipment. Still, we will seek out anomalies on the market that we feel should be reported on – especially popular and well-known products that suffer from significant performance flaws.

On many occasions through the years, advertisers and affiliate merchants have terminated their contracts with us because we (apparently) did not “honor” the unspoken agreement that they were engaged in a financial relationship with us that included the sale of our editorial integrity.

When we make formal recommendations in product reviews (as identified by the Highly Recommended, Recommended, or Guide’s Gear badges), we do so only when:

- We believe the product has a broad appeal to our membership;

- We believe the product’s performance-to-weight ratio is materially better than most of its competitors;

- We have extensive field experience with the product in a wide range of conditions; and

- We have corroborated our findings with others who have extensive field experience with the product in a wide range of conditions.

We make three types of format recommendations:

- Highly Recommended – a product that has a performance-to-weight ratio that is among the highest in its category.

- Recommended – a product that has a performance-to-weight ratio that is substantially higher than most products in its category.

- Guide’s Gear – a product that achieves a high performance-to-weight ratio while providing durability, value, and applicability across a wide range of conditions.

Read more about our review ratings and product review policies in our informational manifesto, About Gear Reviews at Backpacking Light.

Do affiliate commissions introduce bias in our product reviews?

We have affiliate marketing relationships with both networks and merchants (more than 100 merchants – product brands and retailers – as of November 2023).

Affiliate commissions represent less than 15% of our total revenues.

However, we are actively reducing the number of affiliate partnerships we engage in, and who do not support our efforts to bring trusted information and education to our consumer-centric community. Since 2018, we have terminated our relationships with affiliate networks (including Amazon), retailers, and brands who engage in practices that take advantage of consumers, allow fake reviews to proliferate, and do not align with our core value of consumer advocacy.

As our membership revenues grow, we continue to become less dependent upon affiliate income. If all of our affiliate revenues disappeared tomorrow, it would have minimal impact on our ability to keep delivering trustworthy and comprehensive editorial content and serve our membership.

As business owners, employees, outdoor enthusiasts, and consumer advocates, we have strong ideological ties to the principles of:

- Sustainability

- Responsible consumption

- Fiscal responsibility

… and we don’t want to leave a legacy that negatively impacts our environment, your time, or your credit card.

Now, back to the question: do affiliate commissions introduce bias into our reviews?

From the standpoint of our authors and editors, the answer is generally no. Their salary (editors) or honorarium (authors) is never tied to traffic, clicks, or other types of affiliate or advertising performance. In addition, our authors don’t have visibility into our affiliate marketing or advertising business models—an intentional choice on my part to ensure that editorial integrity is their #1 priority. When we hire authors, we recruit them based on their ability to do research, be objective in their analyses, empathize with their audience, and focus on addressing the needs of our members. We do not hire authors based on their “freelance” experience (writing for publishers supported primarily through affiliate marketing and advertising), SEO skills, entertainment value, expression of authenticity, sponsored content experience, or affiliate marketing skills.

When affiliate links are added to our product reviews, they are done at the very end of the production process – writers and editors play no role in identifying prospective affiliate links, adding them to their articles, or otherwise influencing, directing, or being influenced by, our affiliate marketing or advertising strategies. In some cases, links are auto-generated by keyword-matching automation that runs transparently in the background, which adds the links after the page is loaded. For example, this is the process by which most autogenerated affiliate links will appear in user-generated forum posts. When you see a link that points to a URL of the form backpackinglight.com/shop/product-or-brand-name – there’s a high probability that the link was autogenerated by software. (Important: we never edit your forum posts outside of occasional spelling edits as outlined in our Terms & Conditions so our users can find content more effectively inside our site search engine).

When I’m personally developing content for Backpacking Light that includes affiliate links – including articles, podcast episodes, and video education, I’m wearing several different hats – the publisher, responsible for developing and overseeing the business model; the author, responsible for developing a review you can trust because it fairly and honestly presents the product’s performance; the CFO, responsible for the company’s cash flow; the CMO, responsible for growing company sales; and an employee, who gets paid by the company so we can pay our bills at home.

I do recognize and acknowledge that some bias must exist, and you should be aware of that. The existence of this bias cannot be removed in any scenario where I’m generating content and directly profiting from advertiser and affiliate relationships. As Backpacking Light’s owner and publisher, the best possible way to mitigate this is to support company decisions that help grow our membership revenues (which, because they represent recurring revenue streams, are the types of revenue that have the highest impact on our company valuation). Interestingly, this happens primarily through education and skills development, not gear content. This allows me to write about gear with less dependence on having to serve our advertisers or affiliate merchants, and more freedom to provide gear information in the context of product design and analysis education.

Sometimes my INTJ personality paints me into an ideological corner that is hard to escape from, which means that I am inclined to have strong beliefs about how gear should perform. So if you have a reason to distrust my product recommendations, you are more likely to do so based on a clash between what I believe is right and what you believe is right. That’s a clash I can live with, and have respect for. If you challenge me for making product recommendations that appear to be motivated by a thirst for affiliate revenues, then I welcome that challenge and accountability as well – because if that starts happening, then I’ve lost sight of this company’s future.

I hope that you will acknowledge my intrinsic bias as a result of my role in this company, but that it will be compensated for by my experience and background in wilderness travel, product development, entrepreneurial longevity, industry/market awareness, journalistic integrity, and what type of company I want Backpacking Light to be:

One that aims to produce the most authoritative and trustworthy outdoor gear, technology, and skills education available anywhere.

If that resonates with you and you’d be willing to support us on this journey, please consider joining our community and becoming a member. Together, we can fight the good fight to ensure that the real winners of the outdoor industry are those of us who spend time outdoors, and not in boardrooms.

Sincerely,

Ryan Jordan

Founder and Publisher, Backpacking Light

End Notes & Sources

- Outdoor Industry Association. (2022). State of the Outdoor Market Report (Fall 2022). Retrieved March 15, 2024, from https://outdoorindustry.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/OIA-State-of-the-Outdoor-Market-Report-Fall-2022.pdf

- Customer Lifetime Value (CLTV) is a metric used to estimate the total revenue a business can expect from a single customer account during their business relationship.

- Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2022, November). Outdoor recreation satellite account, U.S. and states, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2024, from https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2022-11/orsa1122.pdf

- Quoted from a presentation at Outdoor Retailer Winter 2023 by Julia Clark Day of Circana, an enterprise retail data anlalytics service and platform that provides market tracking information and insights, forecasting, and data management.

- Wellman, M. L., Stoldt, R., Tully, M., & Ekdale, B. (2020). Ethics of authenticity: Social media influencers and the production of sponsored content. Journal of Media Ethics, 35(2), 68-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2020.1736078

- Ebert, I., & Sindermann, D. (2020). An ethical view on influencer marketing – dynamic interaction between individual and economy or a simple data-driven advertising model? In C. Goanta & S. Ranchordás (Eds.), The Regulation of Social Media Influencers (pp. 74–97). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788978286.00012

- Human Brand Theory explores the idea that brands can possess human-like attributes and characteristics, leading consumers to relate to brands in a manner similar to how they relate to other people. See the work of Portal et al. for an example (Portal, S., Abratt, R., & Bendixen, M. (2018). Building a human brand: Brand anthropomorphism unravelled. Business Horizons, 61(3), 367-374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.01.003). Human brand theory is useful for studying the persuasive power of influencer marketing, which flips the script. Instead of building a brand with human-like characteristics, influencers are building a human with brand-like characteristics, allowing the influencer to capitalize on the attachment of followers to influencers in a way that results in the (translated) attachment of followers to the brands and products the influencer recommends.

- Ki, C.-W., Cuevas, L. M., Chong, S. M., & Lim, H. (2020). Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102133